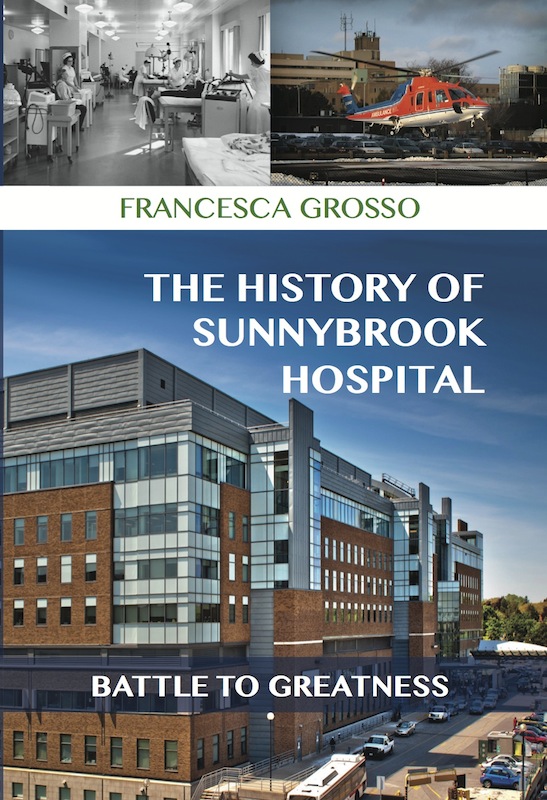

Preface

T he story of Sunnybrook is a story of battle and rebellion in the pursuit of excellence. With each battle endured, Sunnybrook Hospital forged new directions, becoming stronger and greater, often exceeding goals and beating significant odds. The perseverance of many dogged innovators in the face of these challenges enabled Sunnybrook to morph into the dynamic academic health sciences centre it is today.

Presented in three sections, this book takes the reader through the three iterations of Sunnybrooks development: a veterans hospital, born of World War II and of the passionate battles launched by angry citizens to build better hospitals for our returning veterans; a newly named community and teaching hospital, fighting for its very existence, rebelling and innovating to stay alive; finally, a full-fledged academic health sciences centre, struggling to maintain its identity and focus amidst government directed mergers and new diseases.

A great many figures have played a part in the story of what we now call Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. This book tells their stories the stories of pioneers, rebels, and leaders and the stories of the pivotal events and innovations that have shaped Sunnybrooks character and legacy.

Foreword

M y life changed irrevocably at 11:15 p.m. on September 23, 1983. I was finishing my first closing shift at the convenience store where I worked part-time when three individuals wearing ski masks burst in. Before any of them even spoke, one opened fire.

I was eighteen, previously healthy, and I had no reason to know that Sunnybrook Hospital was Canadas pre-eminent trauma centre. But there I was in their emergency department in the early morning hours some forty kilometres from the place where a .38 calibre bullet had torn through my spine from the right side of my neck, lodging in my left shoulder. The bone fragments from my shattered spine were pressing on my spinal cord, causing the most damage in the location where the breathing nerves transmit the messages that control the diaphragm. Although I was able to breathe on my own initially, I very soon required mechanical assistance.

After the shooting, I was first taken to the closest major health care institution, the Mississauga Hospital. However, it was quickly determined that they were not equipped to deal with an injury of the magnitude of mine, so I was transferred by ambulance to Sunnybrook. On call that night was the renowned neurosurgeon Dr. Charles Tator. Tator operated on me, delicately removing bone fragments from the cord and fusing my spine together with a piece of bone from my right hip. This would be one of multiple surgeries performed by Dr. Tator, a key participant in the trauma units establishment.

Once operated on, I was moved to the Surgical Intensive Care Unit, where every patient was on a ventilator and hooked up to a myriad of other machines. This unit would be home for me for three long months. It was a crowded place, with teams of doctors, residents, students, and a host of other specially trained individuals (including pharmacists, clergy, and social workers) in abundance, all focused on many of the hospitals most complicated cases. Despite all of the dedicated care provided by so many talented individuals, it is an indication of just how serious the injuries were of those in the unit that the fatality rate for patients was 25 percent.

As I remember, it also was a loud place, with every patient hooked up to multiple monitors and machines. Alarms rang regularly. Lights would be dimmed later in the evening and staff would make an effort to quiet the atmosphere, but there was no blocking the continual activity, with portable X-ray machines being whisked alongside beds, daily visits by physiotherapists to keep chests clear of infection, and blood work and other tests being performed at regular intervals.

Apart from the hospital crews, family members were obvious regulars, visiting patients in our less-than-private quarters. While each of us had curtains that provided a modicum of physical privacy, there was no hiding what was happening for anyone.

I came to appreciate how great the clinical expertise at Sunnybrook really is as time passed. In particular, the nurses stood out to me as one of the most outstanding groups. In the trauma unit, each patient was provided with a team of two dedicated nurses, who took turns caring for the patient, working in twelve-hour shifts. Each had extra critical-care training and was a highly skilled individual; many had years of experience in intensive care.

Because of my severe paralysis, my entire body required constant care, including bowel, bladder, and skin care. Prevention of complications, like pneumonia, was of paramount importance. Cases like mine require a real a team effort. Fortunately, I was in good hands.

It was a team approach, always, says Annette McCallum, one of my favourite nurses at the time, now a radiologist, and still a friend. There was always help and supervision around, she told me later. The ability to have one nurse per patient was huge [benefit].

My roommates were survivors of trauma and others recovering from major surgery. There were children whose parents were trying to wake them from comas. There were people who had attempted suicide, only to survive as disfigured, disabled, or both. The turnover rate on this unit was high, and the only long-term patients were those with high spinal cord injuries like me.

One of the other patients with spinal cord injuries was a young man who occupied one of the isolation rooms. He was a teenager who had been hit by a police car while crossing a highway. His paralysis was even greater than mine; he had no chance of ever weaning himself off the respirator, and he lived in the unit for an extended period of time before eventually moving to a chronic care hospital. Life had changed forever for both of us. But, unlike me, my unit-mate sadly died as a young man.

Finally, as I began to stabilize, I was moved into the other isolation room. Basic care remained highly specialized and of paramount importance, but the nurses also administered a fair amount of TLC. That might mean talking long into a sleepless night, being a comforting presence while I sobbed uncontrollably, providing compassionate care. There was such kindness.

One afternoon, the plastic tube inserted in the hole in my neck, to which the respirator was attached, needed to be changed. I was terrified, convinced it was going to be a painful experience, affecting one of the few parts of my body where I could still feel. I had my nurse, the head nurse on duty, the anesthetist, Dr. Gil Faclier, who had cared for me through many of my operations with Dr. Tator, and another of the units doctors surrounding my bed. Im sure they spent at least twenty minutes waiting, giving me the time to gather the courage I needed, without showing any impatience. When the procedure turned out to be painless and easy, they didnt make me feel foolish.