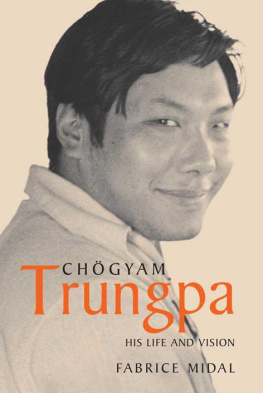

Chgyam Trungpa

HIS LIFE

AND VISION

F ABRICE M IDAL

Translated by Ian Monk

SHAMBHALA

BOSTON & LONDON 2010

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

2001 by Fabrice Midal

English translation 2004 by Shambhala Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Midal, Fabrice, 1967

[Trungpa. English]

Chgyam Trungpa: his life and vision / Fabrice Midal; translated from the French by Ian Monk.1st ed.

p. cm.

Translation of: Trungpa: biographie. Paris: Seuil, 2002.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2186-6

ISBN 1-59030-098-X

1. Trungpa, Chgyam, 1939 2. LamasChinaTibetBiography.

I. Title.

BQ990.R867M5313 2004

294.3923092dc22

2003027653

CONTENTS

PREFACE

I WROTE THIS BOOK IN THE HOPE that, at a time when people are so disoriented that they are open to all sorts of charlatans, the depth and the brilliance of Chgyam Trungpas vision may help them to rediscover their true path.

Beyond the Buddhism that he inherited, beyond any religion, Chgyam Trungpa shows us how we can transform our own existence within our own culture, to discover a sacred world and establish an enlightened society.

My understanding of Chgyam Trungpas work and teachings is so limited that all the reader will find here is an overview. By reading, by gathering testimonials and encounters, I have simply tried to gather together what was disparate in order to help the reader understand the life and work of one of the greatest spiritual masters of our time.

My encounter with Chgyam Trungpa goes back to 1989, when I attended a center in Paris set up by a couple of his American students.

During the subsequent years of practice, numerous meetings with his close disciples, and visits to various centers and meditation and study programs whose content and form he had devised, I was constantly exposed to the extraordinary brilliance of his teaching and its manifestation.

When I started practicing, I found the concrete nature of meditation reassuringthere were no theories or new systems of thought to absorb; instead we were asked to examine ourselves with ever greater curiosity and gentleness. This encouragement to refuse all dogmas delighted the rather short-sighted atheist that I was at the time, devoted to freedom of thought and refusing any kind of manipulation as practiced by the various churches. But as the years went by, thanks to Chgyam Trungpa my preconceptions were obliterated. He opened my eyes. He opened my heart. The existence of a variety of paths allowing human beings to reach attainment appeared to me in places and contexts that I would never have been able to appreciate before. Chgyam Trungpa showed me the true meaning of Tradition.

Without him, I would never have become a Buddhist, because still today I find I have more in common with paths that have nothing to do with that tradition than with various Buddhist groups whose religious, even dogmatic, character is totally alien to me.

When I go to certain Buddhist centers, I may appreciate what goes on there, but I often feel lost and homesickfor the Kingdom of Shambhala that Chgyam Trungpa founded. I miss its freedom, which is like the garuda, a mythical bird that never needs to land on earth.

If I am referring to my personal experience, despite the ignorance I realize it reveals, it is because it proves that it is possible to enter into contact with the teaching of Chgyam Trungpa even though he is no longer physically among us. Chgyam Trungpa continues to open the eyes, hearts, and minds of numerous people, and his presence often overwhelms me.

INTRODUCTION

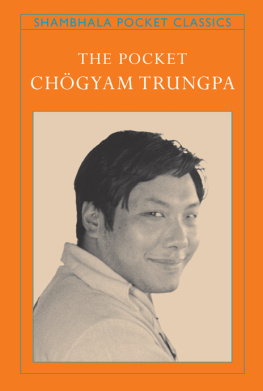

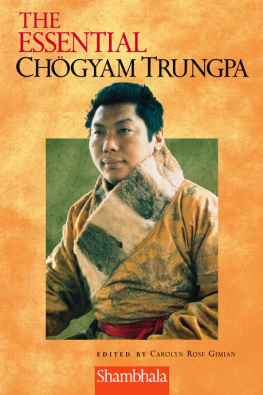

C HGYAM T RUNGPA WAS A Buddhist teacher who was born in Tibet in 1940 and died in Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1987. He was one of the first to teach Westerners, even living with them and sharing their lives.

There are numerous gurus who are known to be true heirs of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. But there is something unique about Chgyam Trungpa. It is difficult to define what is so singular about him, but this book offers an approach.

It is important to note that no other Tibetan guru has so distanced himself from his original culture. A commonly held belief is that spiritual practice is inseparable from its cultural context.

For many years, Zen masters considered that it was impossible to teach Buddhism to Westerners. So their first European disciples took up a Japanese lifestyle.

Chgyam Trungpa never wanted his students to become Tibetan. He believed that when Buddhism is transmitted to the West, it should give rise to a Western Buddhism, and this could only occur after profound reflection about the language and the culture in which the dharma could be established. Such was the huge task that Chgyam Trungpa undertook by immersing himself in the Western world. As he himself explained, becoming a Buddhist is not a matter of trying to live up to what you would like to be, but an attempt to be what you are: This possibility is connected with seeing our confusion, or misery and pain, but not making these discoveries into an answer. Instead we explore further and further and further without looking for an answer. It is a process of working with ourselves, with our lives, with our psychology, without looking for an answer but seeing things as they areseeing what goes on in our heads directly and simply, absolutely literally. If we can undertake a process like that, then there is a tremendous possibility that our confusionthe chaos and neurosis that goes on in our mindsmight become a further basis for investigation.

With this in mind, Chgyam Trungpa paid constant attention to education. He set up several schools and a university; he organized interreligious meetings at a time when they were scarce (while showing a profound interest in Christianity and Judaism, as well as other schools of Buddhism that were little known in Tibet); he was extremely sensitive to the role played by artists, poets, painters, and musicians with whom he regularly worked. He met numerous members of the avant-garde of the time; he analyzed the Wests economic situation and how he could make a significant contribution to it; he gave thought to medicine and how to assuage the ills of the body as well as the mind; he became passionate about politics as a means of living in community and thought deeply about ecology and our relationship with our environment.

In many ways, Chgyam Trungpa is reminiscent of those stained-glass windows, made of a large number of facets, that decorate Gothic cathedrals. Like them, he dazzles you. The only inappropriate aspect of this analogy is that while such prolific richness can seem dazzling, such brilliance can also provoke the greatest terror when it exposes the depth of our own imbecility.

The word imbecile comes from the Latin imbecillus , which means not having a stick. An imbecile is someone with no leaning post. Caught in the web of thoughts changing fashions and habits, he has been lost in obscurity. This is just what Buddhism means by samsara , an endless circle spun by our beliefs and opinions, without the slightest attention to what really is.

The basis of Buddhism, like all authentic practices, is the affirmation that it is possible to find a genuine stick to lean on, that a real world does exist beyond the one we build for ourselves and try to adhere to, come what may.

Next page