FOREWORD

ARRAN IS OR CERTAINLY WAS commonly described as Scotland in miniature on account of its topography, which combines both Highland and Lowland scenery. This splendid book reveals that the island was also a microcosm of what was happening elsewhere in the Highlands in relation to illicit distilling and smuggling during the late 18th and early 19th centuries a fact which has hitherto been overlooked by historians.

Gregor Adamson has done a magnificent job. His research is thorough, even exhaustive, his approach scholarly, his writing lucid and engaging. I learned a lot about a subject which I myself have researched and written about extensively* indeed, this is the best account of smuggling I have encountered.

It is surprising that the subject has been ignored, for the illicit whisky from Arran was considered by connoisseurs to be second only to the same cratur from the Glenlivet district of what is now called Speyside. Private distilling was only banned in 1781; prior to this individuals or communities were entitled to produce whisky for their own consumption, so long as it was made from grains grown locally and was not offered for sale. Of course, these conditions were often ignored and there was an extensive trade in smuggled whisky (the term embraced both illicit distilling and the transportation of illicit goods), and when smugglers were caught and brought to trial, magistrates were usually lenient. After all, judges were often landowners and if their tenants made and sold whisky they were better able to pay their rents.

By the turn of the 18th century smuggling was endemic. The hard-pressed Excise was incapable of subduing it and the increasingly onerous excise duties, imposed by government to pay for the war with France, simply encouraged distillers to operate outside the law. As Mr Adamson writes: By the early 1800s whisky became the chief commodity transported by Arran smugglers as illicit distillation grew to unprecedented levels. But by then landowners were becoming increasingly concerned that if this aspect of the law could be flouted with impunity then further civil disobedience would ensue. Their fear of anarchy was realised during the turbulent years which followed the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars and they pressed the government to address the problem by encouraging illicit distillers to go legal. Ultimately this resulted in the Excise Act of 1823 which laid the foundations of the modern Scotch whisky industry.

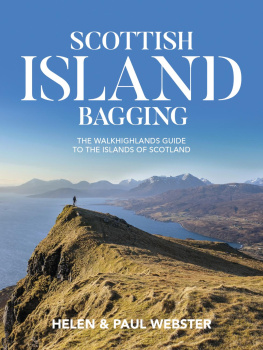

As I have said, all this was reflected in microcosm on Arran except the last, the encouragement to open a legal distillery. This did not come about to any meaningful degree until the opening of the Arran Distillery at Lochranza in 1995, which will be followed in early 2019 by the opening of Lagg Distillery in the south of the island by the same company, not far from the original site of a licensed distillery of the same name which operated briefly in the 1820s and 30s.

I commend this book to you wholeheartedly. It is a fascinating and accurate case study of what has become Scotlands greatest international ambassador and the worlds greatest drink!

Charles MacLean, Master of the Quaich

Singapore, January 2019

*Scotch Whisky: A Liquid History (Cassell, 2003); Scotlands Secret History: The Illicit Distilling and Smuggling of Scotch Whisky (with Daniel MacCannell, Birlinn, 2017)

INTRODUCTION

IT HAS BEEN SUGGESTED that the great Scots poet, Robert Burns, was blind to the natural beauty of his surroundings as he failed to mention the Isle of Arran in any of his literary works, although for many years he viewed the islands scenic grandeur on a daily basis from his native Ayrshire. It could be argued that this ability to turn a blind eye extended to his duties as an Excise officer. Burns enjoyment of whisky and his disdain for the Excise establishment are detailed throughout his works, most notably in The Deils Awa Wi The Exciseman and Scotch Drink.

The capacity to ignore illicit whisky and Arran was not confined to the exciseman Robert Burns. From the scale of illegal production and consumption on the island it would appear that some of his Excise colleagues were afflicted with the same selective blindness in the late 18th century. Arran was a hub of unlicensed whisky distillation during this period, with almost every island tenant engaged in some aspect of this illicit trade. Distilling was vital to the Arran community, becoming ingrained in the islands cultural and economic make-up.

Islanders considered small-scale distilling a birthright, a craft that had been passed down and perfected for generations. Illicit Arran whisky, commonly known as Arran water, was revered for its quality throughout Scotland. Its main market was the Ayrshire coastal towns where it commanded a price equal to, and often exceeding, whisky from the renowned producing districts of Kintyre and Islay. Islanders used a substantial smuggling network to successfully transport the produce of their sma stills to this mainland market. Smugglers often carried out the dangerous sea crossing at the dead of night in the worst possible weather to avoid the attentions of the hated excisemen and feared Revenue Cutters that patrolled the Firth of Clyde.

Excisemen and customs officers were widely unpopular amongst the majority of the islands inhabitants. There are numerous accounts of violent clashes between Arran smugglers and these so-called gaugers, with casualities on both sides. Gaugers were not only obstructed in the exercise of their duty by the ingenuity and cunning of island distillers and smugglers; excisemen on the front line, like Robert Burns, were hindered by ineffective government excise policy which inadvertently encouraged illicit distilling to the detriment of the Revenue and licensed distillers.

By the early 19th century illicit distilling and smuggling had become endemic. There was growing concern amongst the Arran elite that this industry was damaging both the islands commercial viability and the morals of its people. Improvement measures were eventually introduced that slowly eroded the social and economic foundations of the illicit trade. These landowner actions were supported by successful legislative reforms, ending 120 years of excise ineptitude with dramatic implications for Arran distilling and the traditional island way of life.

In addition to its reputation for smuggling, Arran was also home to numerous licensed distilling ventures. In the 1790s, three legal distilleries operated on the island for a brief period. During the boom in small-scale Highland production in the 1820s and 30s, a legal still was also established at Lagg, less than a mile from the site of the new distillery which is currently under construction.

Ultimately, legal whisky production, like so many of the small island industries, ended in failure. By the 1850s, both illicit and legal distilling had faded into insignificance on Arran. Nonetheless, the spirit of the smuggler lived on amongst a few hardy islanders who continued to defy the government into the 20th century. Stills were fired for home consumption often when whisky was scarce and its need was great.

Two centuries ago whisky production was a key element of Arrans economy, in addition to its cultural and social traditions. Distilling remains central to modern-day island life through the success of Isle of Arran Distillers. In the intervening period, however, Arrans rich distilling past was neglected, overlooked by local historians and whisky writers alike. Subsequently, the islands unique distilling story was cast into the shadows of neighbouring whisky-producing areas such as Campbeltown and Islay.