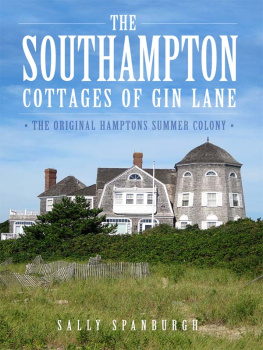

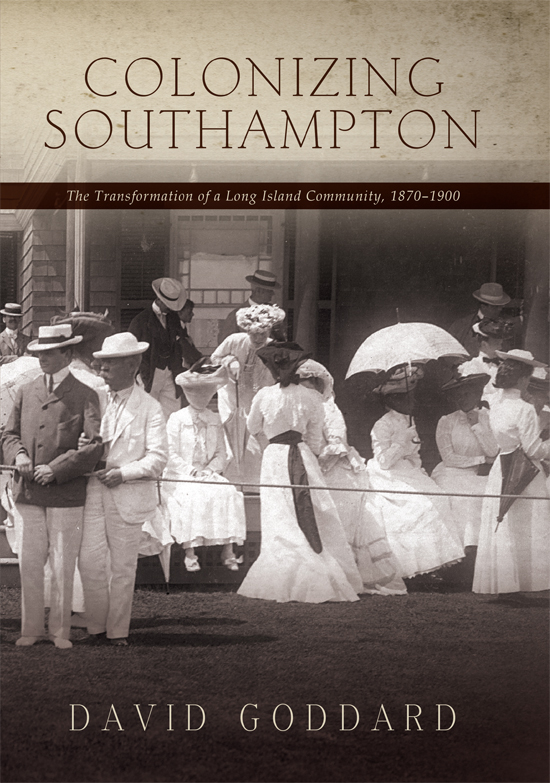

COLONIZING SOUTHAMPTON

The Transformation of a Long Island Community, 18701900

DAVID GODDARD

Cover photo, Collection of the Southampton Historical Museum.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2011 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu

Excelsior Editions is an imprint of State University of New York Press

Production by Kelli W. LeRoux

Marketing by Fran Keneston

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Goddard, David.

Colonizing Southampton : the transformation of a Long Island community, 18701900 / David Goddard.

p. cm.

Excelsior editions.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-3797-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Southampton (N.Y.)History19th century. I. Title.

F129.S7G65 2011

974.7'25dc23

2011022518

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PREFACE

The idea for this book came to me one hot August afternoon in 1998. Adele Kramer, then the director of the Southampton Historical Museum, took me upstairs in the museum on Meeting House Lane to poke around in its somewhat neglected library and archive; in search of what I was not at the time precisely sure. A year or two later, I should add, a generous grant to the museum allowed its board to invest in a considerable upgrading of its library facilities. Ultimately, I was to become a part of this process of expansion.

Meanwhile, in the still, dry atmosphere upstairs I found what I had vaguely been looking for. It was the transcription of a trial, a nineteenth-century court case concerning beach rights in Southampton. It pitted an early summer resident, Frederic H. Betts, against the Trustees of the Freeholders and Commonalty of the Town of Southampton, a venerable body dating back to Southampton's second colonial patent in 1686. Betts had claimed for his own, the beach below his dune property as far as the low water mark. He had even gone so far as to threaten to fence his property off to that farthest point. The gist of the trial concerned who owned the beach and, if anyone did, how far toward the water did that ownership extend. Did it go beyond the line of the dunes as far as low water or only as far as mean high tide? And was ownership a private or public matter? Was the beach town land or was it in private hands and available for sale like any other piece of privately owned real estate? And if it was private, was there a right-of-way on it accessible to the public? These were not settled matters in 1892 when the trial took place before the Supreme Court of the State of New York, but the trial did go a considerable way toward resolving them. But what interested me much more about the case was its exposure of the tensions between an old and traditional community, with a history dating back to the early seventeenth century, and a summer colony of upper-class wealth and privilege that had descended on Southampton from New York as recently as the late 1870s. This new colony was, in numerous ways since then, engaged in a concerted attempt to impose its tastes, interests, and prejudices on what euphemistically might be described as the host community. The trial, in particularly dramatic fashion, shone a powerful light on some of the events of this latter-day process of colonization and on the divisions it created in the community.

I had in fact thought to begin the book with an examination of the issues that were exposed in the Betts trial, particularly because many of the protagonists in the two communities were participants in the proceedings, but in the event left it until the last chapter. The suddenness of the summer invasion and its consolidation as a settled and influential colony in the village of Southampton by 1882, and then its increasing hold over the village after that, seemed to require a good deal of prior explanation. Additionally, I wanted to look at the impact of development projects in the town as a whole in the 1880s that were financed with liberal amounts of external capital originating with New York investors.

These two separate but related processes of social change, neither of them free of conflictthe colonization of the village and efforts at outside economic developmentmarked Southampton's uneasy and sometimes reluctant progress into the modern age at the turn of the nineteenth century. How the town reacted to such rapid change and to the sudden influx of upper-class newcomers, with whom they had little if any previous experience, is the subject of what follows in the chapters in this volume.

There are inevitably many people to thank for their support and assistance in the preparation of this book. In particular, I am extremely grateful for the help extended me by two directors of the Southampton Historical Museum, Richard Barons and Tom Edmonds. I worked under both of them as the museum's archivist and learned much as a result. I am especially grateful to the museum for permission to reproduce a number of photographs from its collection. Emily Oster, the town archivist, extended me every courtesy and full access to the Town of Southampton Archives over a lengthy period of research beginning in 2001. I am similarly grateful to the reference staff of the Rogers Memorial Library for their patience and assistance. Jim Van Nostrand, the village administrator, also was extremely helpful in locating early village records and those of the Village Improvement Association. John Strong, professor emeritus of history at Southampton College (LIU), and Mary Cummings of the Southampton Press and now at the Historical Museum both read the manuscript at various stages. Their comments and suggestions were invaluable in helping me improve it. I also thank Kelli Williams-LeRoux, senior production editor and her staff at SUNY Press for guiding me through the publication process.

Finally, I am as always grateful for my wife Monica's solicitude, forbearance, and advice in the several years it has taken me to write this book.

INTRODUCTION

In September 1863 at the height of the Civil War a young doctor, Theodore Gaillard Thomas together with his wife Mary, took a leisurely trip from New York along the south shore of Long Island. Thomas is generally thought to be the founder of Southampton's summer colony a dozen years later, as well as its spiritual leader. But at that time thoughts of a summer residence in a quiet village by the sea were far from his mind. He was a rising star in the medical profession at the outset of a distinguished career and had no other purpose than to restore his health and seek some relaxation after a long summer in a large and busy practice.

They had taken a light wagon and a good pair of horses, crossed the 34th Street ferry with the intention of heading for Montauk, and set out along the sandy but well-traversed South Country Road through the villages strung out on the shores of the Great South Bay. They stopped at a hostelry at Babylon for two nights and then went on to Quogue, already in the 1860s a small watering spot with several boarding houses that had long attracted hunters and fishermen. Besides sportsmen, Quogue was host to a growing number of summer boarders who stayed either with local farmers or at one or other of the boarding houses. These had sprung up for the most part after 1844 when the Long Island Railroad's (LIRR) single trunk line reached out the length of the island, bisecting it, from Long Island City to Riverhead at the head of Peconic Bay and then to Greenport, a farming and fishing community on the North Fork. Riverhead in eastern Suffolk County was in the nineteenth century a small port and market town with some light manufactures and was also the county seat. A town in itself only since 1792, when it was created by an act of the state legislature, it stood at the boundary of the Town of Southold to the north and Southampton to the south on the South Fork of the island. It had formerly been a village at the western edge of Southold.