Introduction

We know little about King Vikramaditya. Vikramaditya is a title, rather than a name. It means: someone whose valour is like that of the sun. There are emperors who have assumed the title of VikramadityaChandragupta II being an example. But there was also a legendary King Vikramaditya, and scholars do not agree about identifying this legendary King Vikramaditya with any one of the known historical King Vikramadityas.

If you ever visit Ujjain, this illustrious ruler is present everywhere, irrespective of which historical Vikramaditya he is identified with. You will be shown temples built by King Vikramaditya. You will be shown the hill where Vikramadityas throne was buried until King Bhoja discovered it in the eleventh century. Thereby hangs a tale.

Whoever ascended that hill was suffused with immeasurable wisdom. This trait manifested itself in some young cowherds. When this was reported to King Bhoja, he had the hill excavated, and a magnificent throne was discovered; it had thirty-two statuettes. When King Bhoja wished to be seated on the throne, the statuettes restrained him. He was told, This is King Vikramadityas throne. He was a phenomenally wise and great king. To be seated on the throne, you must be as wise as him. Then, one by one, the thirty-two statuettes (each of which was a cursed apsara) told a story about King Vikramadityas wisdom. These stories are collectively known as the Simhasana Dvatrimsika, or Singhasan Battisi. The earliest versions of this text go back to the thirteenth or fourteenth centuries.

The use of the word version is important. There was no printing at the time, and written rendering came much later. Stories were passed down by word of mouth, preserved through oral transmission. Consequently, even though there may have been a common origin, there were regional versions and variations. This is true of the Simhasana Dvatrimsika, as well as of another text associated with the legendary King Vikramadityathat is the one wonderfully adapted in this book.

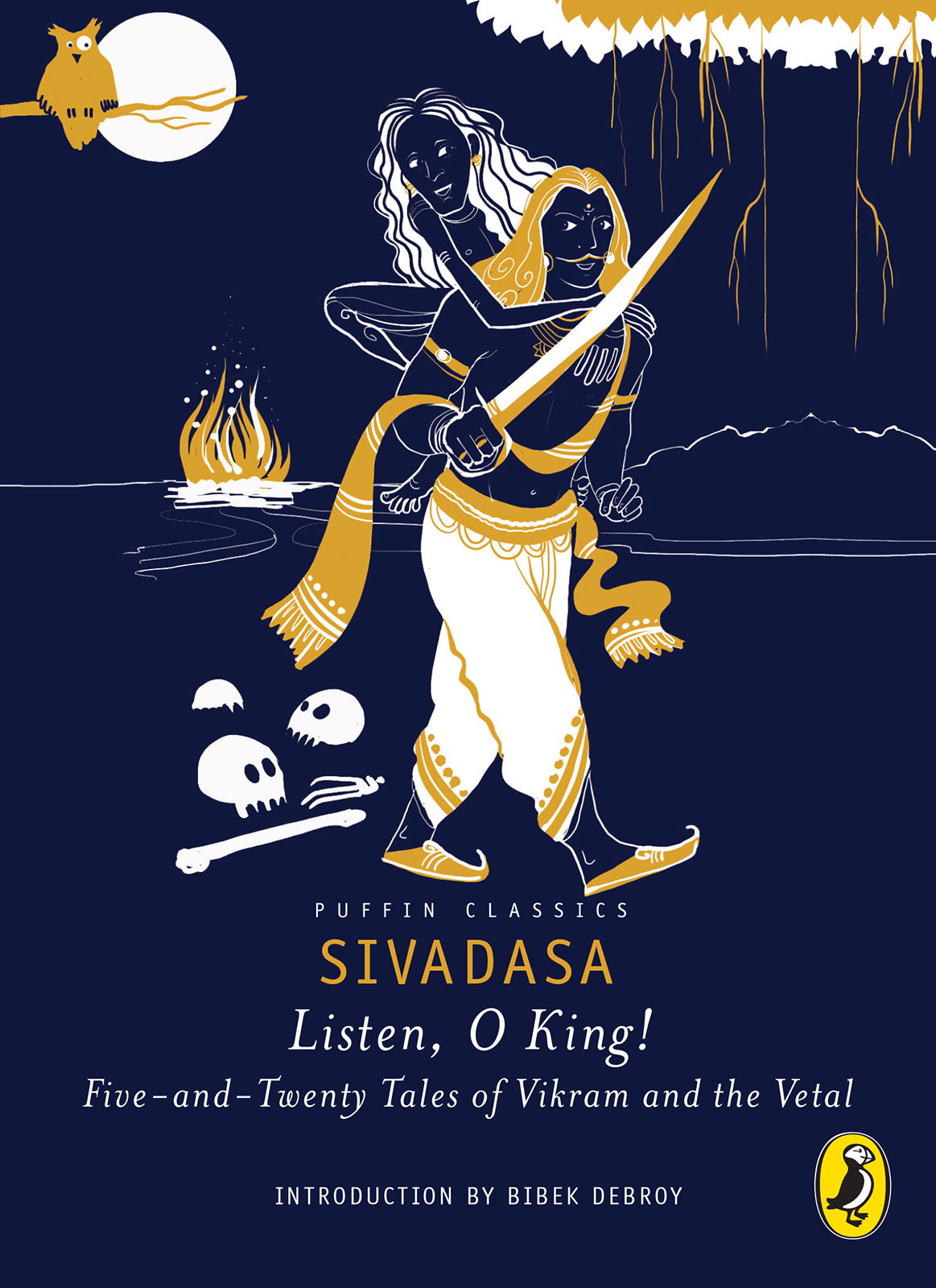

This text is known as the Vetala Panchavimshati, or Baital Pacchisi. A vetal is a demon or spirit, almost always male. But it isnt any arbitrary demon or spirit. Specifically, it is a demon that possesses a dead body with an ulterior motive. This text, thus, has twenty-five stories about the vetal, more accurately, stories about the vetal and King Vikramaditya. Each story has a puzzle, and King Vikramaditya has to solve the puzzle. And it is not as if the solutions are easy.

While in the Simhasana Dvatrimsika, King Vikramaditya is depicted as a historical figure, whom King Bhoja hears about from the statuettes, the Vetala Panchavimshati has King Vikramaditya as the primary protagonist. As a text, the Vetala Panchavimshati is also older than the Simhasana Dvatrimsika. The note on the text gives a very good introduction to its antecedents. Indeed, the roots probably go back further still.

There was a text known as the Brihatkatha, dated around the sixth century and attributed to Gunadhya. It was not written in Sanskrit, but in a language known as Paishachi. Evidently, there is no one around who can speak, understand or read Paishachi any longer. The Brihatkatha can loosely be translated as a large collection of stories.

The Brihatkatha didnt survive, but its derivatives didthose stories were passed down through the ages, and featured King Vikramaditya. They were retold in Sanskrit by Kshemendra and Somadeva. There is a version in Nepal, in Sanskrit, a version in old Maharashtrian prose, another in old Tamil verse. All these derivative stories are based on King Vikramaditya, and not on the Vetala Panchavimshati alone. At one point, Kashmir had a rich heritage of works in Sanskrit. And following from this tradition, there are two Sanskrit versions that specifically narrate the Vetala Panchavimshati. These were written by Sivadasa and Jambhaladatta. Both these texts have been translated into English. As the note on the text later mentions, this adaptation is based on Chandra Rajans translation of the Sivadasa rendering. There are twenty-eight stories, not twenty-five, but the note at the end explains why.

I hope you will read the Simhasana Dvatrimsika some day, too. For some reasonperhaps because of the vetal or because there are engaging riddlesyoung people love the Vetala Panchavimshati much more. Actually, everyone seems to like the Vetala Panchavimshati more. Therefore, despite it having been translated in the past, whats wrong with another adaptation, especially one directed at the young? Enjoy the stories, they are wonderful! By the way, the sinsipa tree (the Indian rosewood) also figures in the Buddhas discourses. Once you grow up and have the time and the inclination, I hope you read them in the original Sanskrit too.

July 2016

Bibek Debroy

How It All Began

King Gandharvasena ruled over the city of Pratishthanpura, that lay on the banks of the river Godavari. A powerful monarch, he had reason to be proud of his might and influence.

One day, the king went hunting in the forest near the city, as he often did. On the way back, he overheard one of his attendants whispering to another, Were very close to where the revered hermit Valkalasana lives.

Who is he? the other attendant asked.

Havent you heard of him? The first one sounded surprised. He is a holy man immersed in the most rigorous penance possible. They say hes been meditating under a nimba tree for a thousand years, without speaking or moving.

Why is he torturing his body so? The second seemed puzzled.

You are a fool! scoffed the first. Dont you know why yogis undertake penance? They do it to acquire superhuman powers. He is determined to gain entry into the heavens and become equals with the celestial beings. Imagine, Valkalasana has disciplined his body to the extent that he can survive on a mouthful of tree bark, which he eats punctually at midnight. The mans voice dropped further. They say... even his excretory functions have stopped.

What? Muffled laughter followed.

The kings mouth twitched too. He had heard of the ascetic but never seen him in person. He recalled what one of his courtiers had said: Your Majesty, he has attained such a supreme state of holiness, they say, that ones sins can be washed away simply by setting eyes on him. Maybe, thought the king, I should go and pay my respects to this extraordinary sage.

Do you know where this saintly hermit lives? he asked aloud. I would like to seek his blessings before I leave this place.

His attendants rushed up, eager to serve him. They guided him to the nimba tree and the king found the yogi seated under it, just as the man had described, in deep meditationso deep that the sound of the horses hooves and the mens chatter did not seem to reach him. He continued to sit there, motionless and silent.