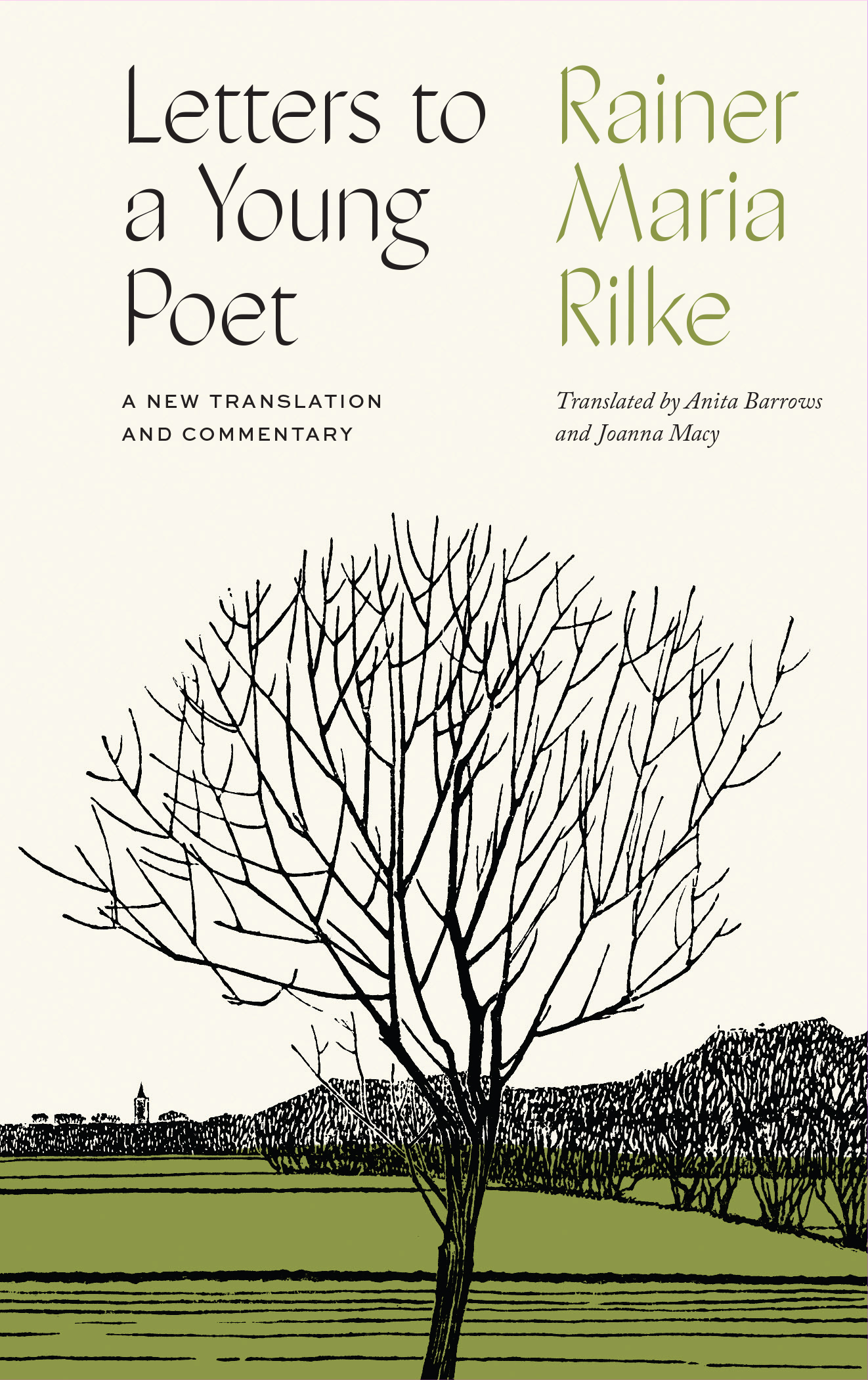

Anita Barrows - Letters to a Young Poet: A New Translation and Commentary

Here you can read online Anita Barrows - Letters to a Young Poet: A New Translation and Commentary full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Shambhala, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Letters to a Young Poet: A New Translation and Commentary

- Author:

- Publisher:Shambhala

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Letters to a Young Poet: A New Translation and Commentary: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Letters to a Young Poet: A New Translation and Commentary" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Anita Barrows: author's other books

Who wrote Letters to a Young Poet: A New Translation and Commentary? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Letters to a Young Poet: A New Translation and Commentary — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Letters to a Young Poet: A New Translation and Commentary" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

4720 Walnut Street

Boulder, Colorado 80301

www.shambhala.com

2021 by Anita Barrows and Joanna Macy

Cover art: Bald tree (1919) by Julie de Graag (18771924).

Original from The Rijksmuseum. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

Cover design: Amanda Weiss

Interior design: Lora Zorian

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For more information please visit www.shambhala.com.

Shambhala Publications is distributed worldwide by Penguin Random House, Inc., and its subsidiaries.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rilke, Rainer Maria, 18751926, author. | Barrows, Anita, translator, editor. | Macy, Joanna, 1929 translator, editor.

Title: Letters to a young poet / Rainer Maria Rilke; translated with an introduction and commentary by Anita Barrows and Joanna Macy.

Other titles: Briefe an einen jungen Dichter. English

Description: First edition. | Boulder, Colorado: Shambhala, [2021]

Identifiers: LCCN 2020032788 | ISBN 9781611806861 (hardcover)

eISBN 9780834843677

Subjects: LCSH : Rilke, Rainer Maria, 18751926Correspondence. |

Kappus, Franz Xaver, 18831966Correspondence. |

Authors, German20th CenturyCorrespondence.

Classification: LCC PT2635 . I65 Z53713 2021 | DDC 831/.912 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020032788

a_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

In the third year of the twentieth century, a nineteen-year-old military cadet named Franz Xaver Kappus, having written some poems, began to wonder if he was really suited to the career for which he was preparing. His academys chaplain happened to see a book of Rilkes poems in the cadets hands. He remembered a former student named Ren Rilke, who had turned to poetry whenever he had a quiet moment. The chaplain suggested that Kappus write to the poet, and the cadet did just that. So began a correspondence that has captured the worlds attention ever since.

In 1929, three years after Rainer Maria Rilkes death, Kappus proceeded to publish the ten letters he had received. The public could see that he never received the kind of assistance he had hoped for, which was critical help with his poetry. Instead, Rilke gave him a far more precious gift: reflections on how to live a life.

Rilke, who was twenty-seven years old when Kappus approached him, had been leading a peripatetic existence in service to the calling that would govern his entire life. Of the poetry that, as a mature poet, he would accept as belonging to his oeuvre, only The Book of Images had been published (1902). Rilke was writing the third volume of The Book of Hours in 1903; until their publication in 1905, the poems of that entire work were known to no one except Rilkes dearest friend and lover, Lou Andreas-Salom. The Book of Images, which includes many of Rilkes most treasured poems, was probably the volume Kappus held in his hands.

Rilke never settled down in one place for more than a few months until World War I confined him to Germany. The letters in this volumeposted from Paris, Viareggio, Rome, Worpswede in northern Germany, and two ports of call in Swedenreflect a life often dependent on the hospitality and generosity of others. This condemned him, of course, to a preoccupied and unstable existence, spending a good deal of time in correspondence about arrangements. He had begun a domestic life in marrying Clara Westhoff, the sculptor, in 1901, awaiting the birth of their daughter, Ruth. He and Clara made a choice to serve their art and allow their daughter to be raised by her maternal grandparents. Rilkes life since childhood had convinced him that solitude was essential to his creativity. He clearly assumed this to be the case for everyone.

Solitude, for Rilke, represented a haven, a freedom from pressures to convention and conformity. He loved the artistic and intellectual pleasures of social gathering but felt fiercely protective of his own idiosyncratic responses to life.

Rilkes commitment to his art shaped his life. That commitment was so total that he expected it of young Kappus himself; if one is going to write poetry, one must feel as though death were the absolute consequence of not being permitted to write. The art Rilke pursued came at great cost; it demanded a deeply authentic response from body and soul to the natural world and to the raw experience of life. Rilke seemed unable to imagine expecting less from Kappus. While this can exalt many would-be poets, it also can be felt as a daunting and almost impossible condition. This certainty of Rilkes was colored by German romanticism.

We find it remarkable that Rilkes devotion to solitude didnt shield him from the unrest so ominously characteristic of the new century unfolding before him. He was able to take in the degradation of urban life and poverty and the loss of the spiritual comforts and certainties that had steadied previous generations.

But when I lean over the abyss of myself,

my god is dark and like a web

a thousand roots silently drinking.

Rilke had already, in the very first poems of The Book of Hours, in 1898, been dismantling the image of the omniscient, omnipotent Sky God, with His unilateral authority, and inviting us to confront what is broken and dark.

We are encouraged to meet and be met by a living world. Rilke senses a reciprocity at the heart of the universe, reflected in his views of sexuality and gender as well as in his views of the sacred. Immediately upon telling the young cadet to go into himself, Rilke also tells him to go into nature. He invites him to welcome what he will find there, trusting that it will lead him deeper into his true identity.

Although Rilkes views on sexuality and gender might not seem radical to us, they were revolutionary for his time. For Rilke, art and sex, in the broad, clean sense, originate in Eros and share the same longing and rapture. Sexuality, like art, deserves to be freed from anything narrow, spiteful, and time-bound. In his critique of the poet Richard Dehmel, in the third letter, Rilke shows how sex has been harmed by the masculine tendency to lust, thrust, and restlessness.

Rilke says something fresh to us as were seeking gender equality today: he would free us from oversexualizing our gender and urge us, as lovers, to become simply two humans helping each other bear the burdens and calling of our sexuality.

When Rilke speaks, in Letter Seven, of two solitudes that protect, border and greet each other, a phrase adorning many wedding ceremonies, he invites us to continue a deep reciprocity between the partners. Reciprocity, in Rilkes view, also characterizes our relationship with the Divine. After reassuring the cadet that he cannot lose God, as Kappus had feared, Rilke suggests that he could actually be engaged in bringing God forth. This is a stunning notion: that Godthe One who is comingis coming from all that we ourselves are and will be in the process of understanding and generating. If God is not a fixed, eternal being, but one we are moving toward and helping to evolve, then our relationships can only be journeys of reciprocity. In this journey, uncertainty is both unavoidable and essential, however paradoxical that might seem.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Letters to a Young Poet: A New Translation and Commentary»

Look at similar books to Letters to a Young Poet: A New Translation and Commentary. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Letters to a Young Poet: A New Translation and Commentary and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.