Humanism in Practice

Series Editor

Anthony B. Pinn

Rice University

Institute for Humanist Studies (Washington, DC)

Humanism in Practice presents books concerned with what humanism says about contemporary issues. Written in a reader-friendly manner, the books in this series challenge readers to reflect on human values and how they impact our current circumstances.

Pitchstone Publishing

Durham, North Carolina

www.pitchstonepublishing.com

Institute for Humanist Studies

Washington, DC

www.humaniststudies.org

Copyright 2017 by Anthony B. Pinn

All rights reserved

Printed in the USA

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pinn, Anthony B., author.

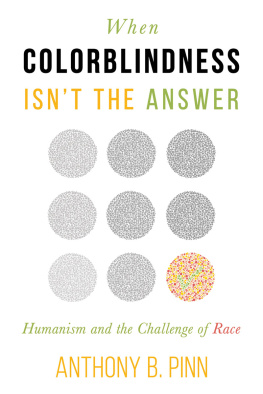

Title: When colorblindness isnt the answer : humanism and the challenge of race / Anthony B. Pinn.

Description: Durham, North Carolina : Pitchstone Publishing ; Washington, DC : Institute for Humanist Studies, [2017] | Series: Humanism in practice

Identifiers: LCCN 2016052927| ISBN 9781634311229 (paperback) | ISBN 9781634311243 (epdf) | ISBN 9781634311250 (mobi)

Subjects: LCSH: HumanismUnited States. | Humanism, Religious. | Race--Religious aspects. | United StatesRace relationsReligious aspects. | BISAC: SOCIAL SCIENCE / Ethnic Studies / African American Studies. | PHILOSOPHY / Movements / Humanism.

Classification: LCC B821 .P473 2017 | DDC 144dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016052927

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The idea for this book and the series of which it is a part stem from a panel discussion at one of the American Humanist Association annual meetings. I want to thank the staff of the American Humanist Association, particularly Maggie Ardiente, and the editor of The Humanist, Jennifer Bardi, for their encouragement and willingness to give the ideas presented in these pages their first hearing. Thanks also to Drs. Sikivu Hutchinson, Monica Miller, and Christopher Driscoll for participating in that panel discussion and for the insights they shared. As always, I want to thank family and friendsparticularly, in this case, Herb and Linda Kelly for their good humor and much needed time away from the computer. I must also thank the Institute for Philosophical Research (Hannover, Germany) for space to write and important conversations regarding humanism.

The idea wouldnt have survived the plane ride home and a few minutes of thought in my office if not for Kurt Volkan. Thanks, Kurt! Finally, I must offer my thanks to Free Inquiry for permission to reprint an essay first published in that journal (now in this volume).

INTRODUCTION

There are debates, heated discussions really, within the humanist movement (of which I consider myself a part) revolving around the agenda that should guide humanist thinking and activism.

Is it enough to address separation of church and state? Of course, science education should be high on the list of key issues meriting humanist time and resources, right? And, public policy is certainly the context in which reason and logic are celebrated and highlighted as necessary for the proper working of democracy. This, as an element of humanist activism, is a given, correct? These are just a few examples of the activism possibilities that receive energetic conversation and attention within the humanist circles familiar to me. Such issues and debate, in a significant way, have shaped the public presence and look of humanism for some time now.

One can think about these issues Ive mentioned as marking out how humanists understand their world and interact with that world. That is to say, such issues or platforms have something to do with the interactions of humanists individually and within the context of collectives called communities, social groupings, and so on. But these platforms, at least for some of us, raise the question: what does humanism have to say to and about those bodies at work within both private and public realms? Let me explain why I bring up bodies and what I mean to suggest by this attention to bodies.

Without getting too philosophical, these bodies are material (i.e., born, live, and die), but we also know them as social constructs or a type of cultural thing. That is to say, by the latter point, what we know about our bodies is determined by what we can speak (through language) about these bodies. I suggest humanists understand without significant trouble or confusion the materialbiologicalreality of bodies. However, humanists have a more difficult time understanding and addressing the social construction of these bodies.

The formerthe biological realitybends to logic and science, while the social construction of bodies has no necessary logic and isnt defined by the assumed objective findings of science. Perhaps it is this differentiation between material and social bodies prompting some to argue social issuessuch as racismarent fundamental to humanism and its activists? In a word, the position for some goes this way: if science doesnt hold the key to understanding an issue, or if logic and reason alone cannot address an issue, then that issue isnt a pressing concern for humanists.

Despite the thinking Ive suggested above, so many of the speaking invitations I receive from humanist organizations and communities revolve around questions not guided by a scientific, its-got-to-be-reasonable approach to engagement. These questions seekalbeit in sloppy waysto recognize socially constructed bodies as bodies worthy of attention: How do we get more African Americans into the movement? Or, why are so many African Americans still involved in a religious tradition (i.e., Christianity) that was used to enslave them and that continues to justify racial discrimination, among other modes of injustice? Both questions point out an example of the social significance of raceand its enactment in the mode of racismwhile also suggesting a desireat least on the part of someto address race as a humanist issue.

I am one who has argued for a few decades now that humanism should address issues of social injustice, like racism, as part of its commitment to the well-being of life in general and human flourishing in particular. To omit attention to modes of social injusticelike racismis to reduce the connotations of the human in humanism. Furthermore, it is to truncate the challenges confronting human well-being in the contemporary world. And so, I typically accept invitations to talk about humanism and race, and to offer historical perspective and prospects. Those lectures take a good amount of time out of my schedule. And, as I make my way from the stage to the hallway, the exchanges postlecture add a good number of minutes to my interactions with humanist community members. I have no complaints about the time I spend talking about humanism and race. Im glad to give those presentations.

Yet, recent conversations concerning a definition of humanism and its mission motivate me to offer something more concise, certainly more condensed and bite-size then the talks and lectures. At one American Humanist Association (AHA) annual gathering my effort to provide a thumbnail platform on social injustice took the form of a list of donts and dos for humanists interested in issues of race and racism. I think its worth sharing in greater detail some of those thoughts and challenges.

Next page