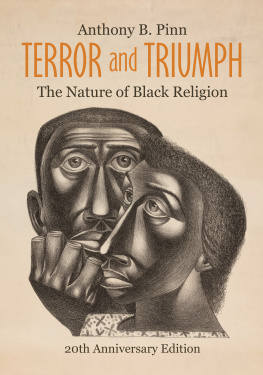

Terror and Triumph

T HE 2002 E DWARD C ADBURY L ECTURES

U NIVERSITY OF B IRMINGHAM, U NITED K INGDOM

Terror and Triumph

The Nature of Black Religion

20th Anniversary Edition

Anthony B. Pinn

Fortress Press

Minneapolis

TERROR AND TRIUMPH

The Nature of Black Religion

Copyright 2022 Fortress Press, an imprint of 1517 Media. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher. Email or write to Permissions, Fortress Press, PO Box 1209, Minneapolis, MN 55440-1209.

All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are from the King James Version.

Scripture quotations marked (RSV) are from Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1946, 1952, and 1971 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Cover image: We Have Been Believers, 1949, Lithograph on wove paper The Charles White Archives (Sourced by The Art Institute of Chicago through Art Resource)

Cover design: Kristin Miller

Print ISBN: 978-1-5064-7473-1

eBook ISBN: 978-1-5064-7474-8

While the author and 1517 Media have confirmed that all references to website addresses (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing, URLs may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

To Dr. Charles Long, Dr. Gordon Kaufman, and the Ancestors

Contents

Robert Beckford

Keri Day

Sylvester Johnson

Anthony G. Reddie

Calvin Warren

Carol Wayne White

The generous invitation to give the Edward Cadbury Lectures at the University of Birmingham (UK) was the first occasion to systematically think through the issues that define Terror and Triumph. But my sense that there was a need to reevaluate theory and method for the study of Black religionin a sense to bridge my training as a constructive theologian with my growing concerns more deeply associated with religious studiespredates these lectures. For example, Varieties of African American Religious Experience (1998) marked my early interventionoutside the clearing of space for serious consideration of religiosity beyond the culture of Black churchesin the form of a nascent comparative Black theology aiming to promote an alternate vocabulary and grammar for the religious within African American communities. However, a more expansive theological grammar and vocabulary capable of holding in tension competing faith claims wasnt enough. While I continue to value that move, and I hope it has been of use to the fields of religious studies and theological studies, it is limited to those traditions for which theological articulation means something. This is my way of saying it was an intellectual move that most clearly meant a mode of linking divergent religious traditionsthat is, those modalities of thought/practice marked by doctrines, creeds, ritual structures, and hierarchies of involvement or those, like humanism, so new to the study of Black religion that theyd not achieved solidity of presentation in a way that excluded such considerations. That is to say, Varieties of African American Religious Experience assumes presentation of religiosity through certain structural markers and a particular guiding logic: for example, humanism is to religion as Black churches are to religion.

It didnt go far enough. That project continued to assume too much. It failed to name and address dimensions of religiosity that cant be funneled easily through the hermeneutics primarily in usenot even when framed in terms of extrachurch orientations offered by Charles Long in his brilliant Significations. I dont know that either Kaufman or Long saw themselves reflected in Terror and Triumph. And some of Longs students made it clear that what I offered had little to do with Longs work. However, such a critique, while it helped me in a variety of ways, misses the aim of the text. It wasnt an effort to simply think like Long and Kaufman but rather an effort to think with them in order to come up with my own theoretical formulation of religion.

One of the questions guiding Varieties of African American Religious ExperienceWhat are the commonalities between opposing modalities of religiosity?is present also in Terror and Triumph. However, the turn to psychological and affective dimensions of the question pushed me to consider what is taking place below the historical markerswhich is to say a more fundamental materiality of Black religionand to consider what motivates what we have traditionally called Black religion. Attempting to avoid a problematic reductionism, I wanted to expose what I believed was an underlying prompt that takes concrete form in the data typically presented in the study of Black religion. Thinking about Longs sense of two creations, and the effort to crawl back to the first creation, got me thinking about the making of Black beingsthat is to say, the transformation of Africans into African Americans.

There was something therein that transformationthat spoke to the creation of Black religion that reveals the outline of its meaning and intent. Not the Middle Passagethat death-dealing journey from familiar geography to foreign and brutal lands marked by the experience of a certain type of metaphysical warping that existing grammar and vocabulary of personhood was ill-equipped to express and explorewhich gave some shape to the dwarfing of Black being that prompted a cultural response. But it didnt mark the dehumanization bottom encountered in that (1) the uncertainty of their condition, the gap in the presentation of their new circumstances and relationship to whiteness, meant dehumanization wasnt fully encountered on the ships. They were othered, but the process wasnt completed on the boats; (2) the descendants of those who survived the Middle Passage didnt have direct encounter with that watery experience of othering. I thought this push against the centrality of the Middle Passage might generate more critique than was the case. Perhaps that was due to the undeniable significance of what I pointed to as the moment of dehumanization (being radically othered) fully felt. The auction blockthe ritual performance of objectification by means of which Black people are transformed into toolsmarked, I argued and continue to believe, the fuller weight of dehumanization felt and borne. It is an early ritual of reference by means of which the otherness of Black people is solidified through public spectacle. And with the end of the institution of formal slavery, the auction block was followed by other rituals of reference that marked Black statusfor example, lynching (and more recently, the cases of murder by police protested through the Movement for Black Lives, more popularly called Black Lives Matter).

My theorization of religion as the quest for complex subjectivity marks the othering experienced with the auction block, for example, as the impetus for the formation of Black religiosity. That is to say, I understood religion as the effort to constitute life meaning over against the warping of being forged through whiteness.

Over the years, in light of invaluable conversations and responses to the book, Ive modified my thinking of this quest for complex subjectivity. Ive rethought this theory of religion, and I offer this modification in a new book (Interplay of Things: Religion, Art, and Presence Together

Many assumed that my theorization only applied to

Next page