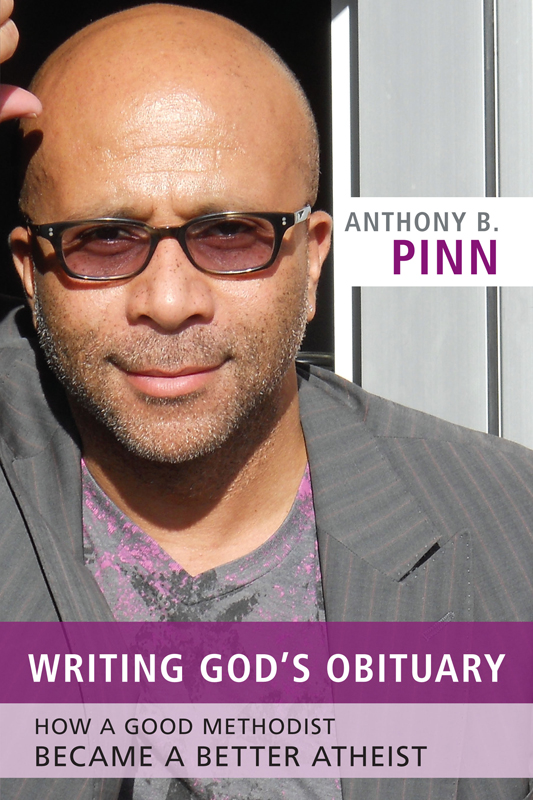

Published 2014 by Prometheus Books

Writing Gods Obituary: How a Good Methodist Became a Better Atheist. Copyright 2014 by Anthony B. Pinn. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Prometheus Books recognizes the following registered trademarks mentioned within the text: Facebook; IBM; La-Z-Boy; Teflon; Wrangler.

Cover image Dr. Caroline Levander

Cover design by Grace M. Conti-Zilsberger

All interior images are from the authors personal collection.

Inquiries should be addressed to

Prometheus Books

59 John Glenn Drive

Amherst, New York 142282119

VOICE: 7166910133

FAX: 7166910137

WWW.PROMETHEUSBOOKS.COM

18 17 16 15 14 5 4 3 2 1

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Pinn, Anthony B.

Writing God's obituary : how a good Methodist became a better atheist / by Anthony B. Pinn.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-61614-843-0 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-61614-844-7 (ebook)

1. Humanism, Religious. 2. Humanism--United States. 3. African Americans--Religion. 4. Religious biography--United States. 5. Pinn, Anthony B. I. Title.

BL2760.P57 2014

211'.8092--dc23

[B]

2013036313

Printed in the United States of America

The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible.

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891)

I would hurl words into this darkness and wait for an echo, and if an echo sounded, no matter how faintly, I would send other words to tell, to march, to fight, to create a sense of the hunger for life that gnaws in us all.

Richard Wright, Black Boy (1945)

Why arent more African Americans atheists... I mean, in light of how Christianity was used to enslave them?

Over the past twenty yearsthe time period during which Ive done most of my writing and speaking about African American humanists, atheists, and freethinkersI have heard some version of this question too many times to count. It has peppered Q&A sessions after presentations Ive given, and it has followed me down the aisle of many lecture halls.

I dont doubt the question is genuine. But all too oftenas I cover my frustration with a smile and a pause before respondingI offer a reply knowing the question is framed by a real lack of knowledge about African American culture and how religion fits into it. And the question often overlooks any recognition of the firestorm that can accompany an African American saying, Enough of this madness. I dont believe, and I wont sit passively in a church any longer. The famous line from the movie Network, Im as mad as hell and Im not going to take it anymore, applied to African American religion, comes with consequencesanything from mockery to isolation on a variety of levels.

Making this proclamation of disbelief gives people pause, but it doesnt mean African Americans havent taken this step and made pronouncements of their godlessness under their breath. Others have acted out, with a smile covering their anger, this shift away from the church in passive (passive-aggressive) ways. Others, like me, have taken it further and made public statements concerning the irrelevance of theism to the meaning of life.

But to understand this last response, to think about an African American presence in humanist and atheist communities, requires something more than a quick turn to pieces of popular literature by spokespersons of the New Atheism. You have to know something about us.

Writing Gods Obituary is an effort to close this gap by clearing the fog surrounding African American humanism and atheism through the story of how one African American became an atheist. What I have heard and experienced over the yearsthe quick conversations off to the side, the questions after formal presentations, the e-mails, Facebook posts, and phone calls from other African Americans who find something familiar in my storygrounds my belief that my story says something about more than just me.

My lifethe way the church captured me and shaped me, the development of community and relationships read through the archaic demands of the Bible, the overlooking of life for the benefit of some type of spiritual hope for something better beyond this world, the stifling theology that prevents questioning and thinkingcontains something of the stories of others.

I hope other atheists reading my story will appreciate my celebration of our way of life and its diversity, and that those not in our community will find in it a way to do what most theists find difficult (and unnecessary): to see and acknowledge atheisms complexity, passions, purpose, and human face.

This book isnt meant to be preachy; it isnt a rabid condemnation of theism. Instead, through my story, with all the gaps and challenges posed by memory, it shows how the very idea of God gets written out of the life of some simply because God and the stuff of belief in God dont function, dont measure up against the compelling demands of life. While not exact, and between the holes in what I can recall, I believe it still tells of how one person stopped trying to be a good Christian at the expense of his integrity, and became a better atheist with his ethics and moral code intact.

I am responsible for the content of this book (and all the photographs are from my personal collection), but I would like to thank my family and friends for their encouragement and support over the years. I must also thank two of my graduate students for their assistance. Biko Gray worked to make certain the photographs were in proper form, and Jessica Davenport prepared the completed manuscript for submission to the publisher, consistent with its style guidelines. Thank you. Finally, I offer my sincere thanks to the staff of Prometheus Books for such careful handling of this project, and for good humor and kind words along the way.

We dont pick the circumstances surrounding our births. If we did, I might have chosen a different location. Nothing against Buffalo, New York, but it doesnt have the depth or sophistication I find myself drawn to now.

My family lived between Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Park and Delaware Park. While Delaware Park was pristine and solidly middle class, King Park was closer to downtown, closer to the Fruit Beltan area of the city, oddly enough, named after fruit but housing some of the most dangerous activities in the city. My stretch of the city, between these two public markers, was working class. But as you moved from King Park toward Delaware Park, the people in the houses in general got lighter in complexion and more solid in their economic position in the city.

Its not that my section of the city was Hollywood-movie bad, but the economic challenges were clear when you looked at it from the suburbs or from the other side of Delaware Park. We always had the basics and more; we were comfortable. My needs were met and most of my wants were addressed. At times we robbed Peter to pay Paul, as the expression goes, although it would be some time before I knew this was the case.