.

If you would like to see a full list of the e-books Stenhouse offers, please visit us at www.stenhouse/allebooks

Stenhouse Publishers

www.stenhouse.com

Copyright 2018 by Matthew R. Kay

All rights reserved. This e-book is intended for individual use only. You can print a copy for your own personal use and you can access this e-book on multiple personal devices (i.e. computer, e-reader, smartphone). You may not reproduce digital copies to share with others, post a digital copy on a server or a website, make photocopies for others, or transmit in any form by any other means, electronic or mechanical, without permission from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders and students for permission to reproduce borrowed material. We regret any oversights that may have occurred and will be pleased to rectify them in subsequent reprints of the work.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kay, Matthew R., 1983- author.

Title: Not light, but fire : how to lead meaningful race conversations in the classroom / Matthew R. Kay.

Description: Portland, Maine : Stenhouse Publishers, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018004786 (print) | LCCN 2018019979 (ebook) | ISBN 9781625310996 (ebook) | ISBN 9781625310989 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Multicultural education--United States. | United States--Race relations--Study and teaching | Group work in education. | Discussion. Classification: LCC LC1099.3 (ebook) | LCC LC1099.3 .K39 2018 (print) | DDC 370.117--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018004786

Book design by Blue Design (www.bluedes.com)

Manufactured in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

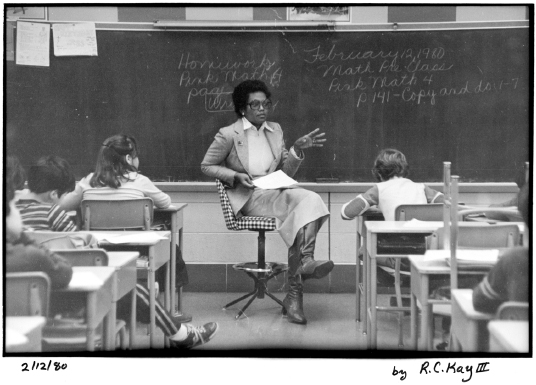

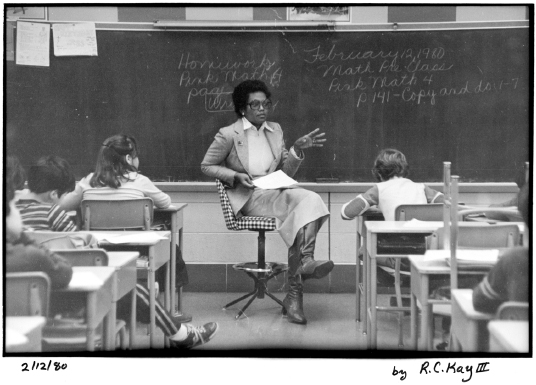

In loving memory of Sherrill Jones Kay, my mother, a thirty-six-year teaching veteran and the reason I do what I do.

Ive decided to keep you.

CONTENTS

IntroductionNot Light, but Fire:

The Case for Meaningful Conversations

Chapter 6Say It Right:

Unpacking the Cultural Significance of Names

Chapter 7Playing the Other:

Thoughtfully Tackling Cultural Appropriation

Chapter 8Pop-Up Conversations:

Lessons from the 2016 Presidential Election

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I d like to thank my wife, Cait, for providing honest, insightful, and comprehensive feedback on every draft of this book; my father, Rosamond, for the decades of mind-sharpening debate that model the discourse I want for my students; and my aunt Connie, for her unconditional love and support.

Thanks to my principal and great friend, Chris Lehmann, for all the professional opportunities that led to the writing of this book. I will always be grateful to my editor, Tori, for her patience, expertise, and encouragement.

Finally, thank you, Dia. You were a perfect gift, just in time. Daddy loves you.

INTRODUCTION

NOT LIGHT, BUT FIRE: THE CASE FOR MEANINGFUL CONVERSATIONS

T alk is cheap. We have built a mountain of clichs to say as much and a canon of stories to indict the boastful rabbits and loose lips among us. History praises Lincoln for his brevity at Gettysburg, while it forgets Edward Everetts two-hour speech that preceded it. Shakespeare made sure that Hamlet punished Poloniuss sermonizing with an ignoble death-while-hiding. And lest the bards point go unmade, the wavering prince meets his own end only after letting his righteous revenge dissolve into words, words, words. The most garrulous among us are dismissed as weak-willed; many hate a windbag, most fear the silver-tongued. Knowing that those who talk long often talk wrong, we have developed a uniquely American succinctness. We expect to be sold ideas in the time it takes to ride an elevator, and to be able to judge their merits just as quickly.

Yet, moments of racial tension scratch from us a great tolerance for empty talk. There is a certain formula a racial story can reach, some unknown combination of timing, rarity, and the notoriety of those involved that draws analysts to gravely suggest that we need to talk about race. And then we do. A lot. With little regard for substance or coherence, we find our airwaves filled with empty rhetoric and thoughtless repetition. Consider, for example, the following race conversation from our nations not-too-distant history. In March of 2008, ABC News unearthed some of the Reverend Jeremiah Wrights sermons, highlighting lines like, The government gives them the drugs, builds bigger prisons, passes a three-strike law, and then wants us to sing God bless America. No, no, no, not God bless America, God damn America! Thats in the Bible! For killing innocent people. God damn America for treating us citizens as less than human! And this excerpt responding to 9/11 that borrows from Malcolm Xs comments after the Kennedy assassination: We have supported state terrorism against the Palestinians and black South Africans, and now we are indignant! Because the stuff that we have done overseas is now brought right back into our own front yard! Americas chickens are coming home to roost (Wright 2008). After trying in vain to quell the controversy about his pastor, then senator Obama was forced to deliver his celebrated More Perfect Union speech, where he acknowledged that Wright had used incendiary language to express views that had the potential to not only widen the racial divide, but views that denigrate the greatness and the goodness of our nation. Later, Obama argued that

we have a choice in this country. We can accept a politics that breeds division, and conflict, and cynicism. We can tackle race only as spectacleas we did in the OJ trialor in the wake of tragedy, as we did in the aftermath of Katrinaor as fodder for the nightly news. We can play Reverend Wrights sermons on every channel, every day and talk about them from now until the election, and make the only question in this campaign whether or not the American people think that I somehow believe or sympathize with his most offensive words or (Obama 2008)

He then pivoted to a plea for post-racial populism, challenging Americans to talk about crumbling schools, jobs, and health care. The speech was received well enough to inspire T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting to gather a collection of scholarly essays written about it into a book titled The Speech: Race and Barack Obamas A More Perfect Union (2009). Eminent scholars such as Michael Eric Dyson and Ta-Nehisi Coates contributed. But, considering this race issue settled, the public conversation had already moved on. The issue flared back up, however, soon after our countrys first black president was elected, when Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates was arrested in front of his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Six days later, President Obama claimed that the arresting officer had acted stupidly, and the call for conversation went out again. Many of us remember the resulting beer summit, where the involved parties talked reconciliation near the White House Rose Garden.

More recently, we have collectively held forth on the Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Eric Garner decisions; riots in Baltimore; shootings in Charleston; and the burning of black churches. As supremacists march, we talk. As confederate statues come down, we talk. We tweet, we post, we meme, we chat. Our news networks cram eight analysts into eight tiny boxes, then pit them in a moderated struggle to be the most quotable.

Next page