Work is more than just your way of making a living: its your passion! Every day, you throw everything you have into accomplishing your tasks, delivering quality and reaching, or even surpassing, your goals. You are conscientious, a perfectionist even, and you aim for recognition at all costs. With this in mind, you never object to taking on work and dont think twice about working overtime. The first to arrive and the last to leave, you tend to take work home just to finish off. You push yourself to the limit and are brimming with motivation and energy. You always do more, but could you be doing too much?

Over time, your relaxation time gets shorter and evenings with family and friends become rare. Your mind is constantly on work, leaving no space for your private life. And deep down inside you, there is a ball of stress that never goes away. Your tired, worn-out body can no longer keep up with this hellish pace. Faced with overload, you are no longer up to the challenge: you make a string of mistakes, you have lost your taste for work and a feeling of failure overwhelms you, to the point that you lose all your self-esteem. The process began without warning, and you never saw it coming. You realise now but it is too late: burnout has taken hold of you.

How can you avoid getting to this point of no return? Learn to protect yourself, listen to your body and strike a balance. Spot the warning signs of burnout and identify risky behaviours before you lose control for good.

Burnout: the basics

What is burnout?

For more than a decade now, the media has been warning us about this scourge of modern times: burnout. The verb to burn out literally means to become or cause to become worn out or inoperative ( Collins English Dictionary ). As such, a person who is burnt out is so exhausted by their work that they can no longer function. They feel intense physical and psychological fatigue, resulting from a feeling of powerlessness and despair.

Burnout in literature

The concept of burnout is inspired by the aerospace industry. Originally, the term described a rocket which was running low on fuel and whose engine had overheated, putting it at risk of explosion.

The word burnout was first used in an article to designate a psychological phenomenon specific to the world of work in 1969. The author, Harold Bradley, recommended putting in place a structure designed to protect probation officers working in a community-based treatment programme for juvenile delinquents from burnout.

In 1974, burnout was the subject of a new article written by Herbert Freudenberger. Freudenberger, who was a psychologist in a drug addiction clinic in New York, described the process of demoralisation, disillusionment and exhaustion that he noted in volunteers. The psychoanalyst and doctor had himself suffered from burnout on two occasions, and this no doubt contributed to the credibility of his writing on the subject. Today, he is considered to be the spiritual father of the concept. Through the metaphorical image of an inner burning, Freudenberger compares individuals to buildings which have been struck by fire:

What had once been a throbbing, vital structure is now deserted. Where there had once been activity, there are now only crumbling reminders of energy and life. Some bricks or concrete may be left; some outline of windows. Indeed, the outer shell may seem almost intact. Only if you venture inside will you be struck by the full force of the desolation. (Freudenberger and Richelson, 1980)

In 1976, as part of her research in social psychology, Christina Maslach expanded the concept of burnout, which until then had been limited to mental health professionals, to cover all individuals whose jobs require a high level of emotional and social commitment. This group includes not only medical staff, but also social workers, teachers and lawyers.

Burnout today

Since it was first accepted, the definition of burnout has constantly been fine-tuned. Although many doctors and authors have addressed the issue, they all agree on one point: the source of the process can be found in the professional environment. While it was thought in the 1960s that burnout was limited to the helping professions, since the end of the 1980s analysts and doctors have agreed that the syndrome affects a much larger proportion of workers: it is a genuine social phenomenon and no sector of activity is completely free from it. Research is still being carried out on the problems potential contributing factors and treatment.

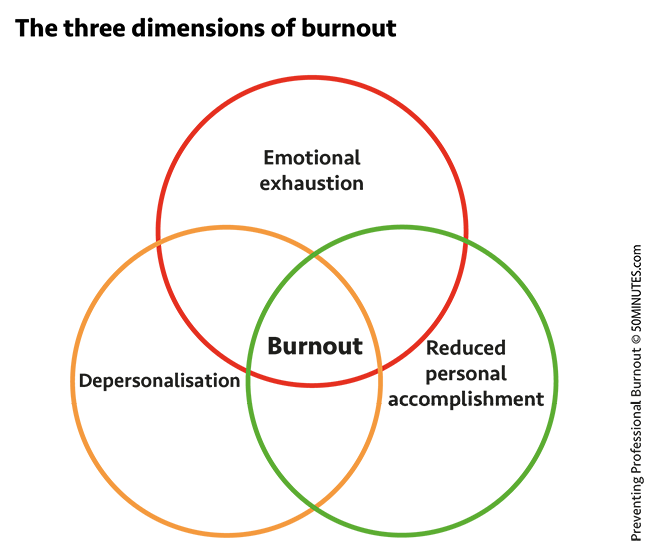

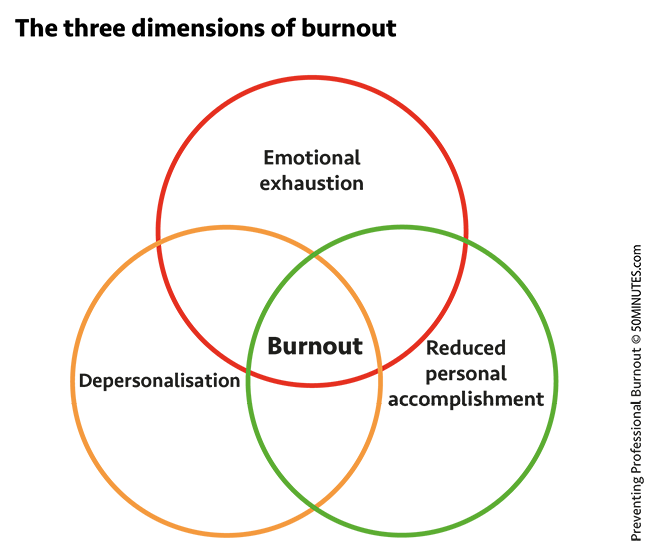

The three dimensions of burnout

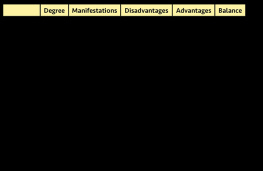

The studies carried out by Christina Maslach made a major contribution to the definition of the main characteristics of burnout and its diagnosis at the end of the 1970s. In 1981, alongside the psychiatrist Susan Jackson, Maslach dedicated herself to developing a method which would allow the syndrome to be measured. To do this, Maslach and Jackson identified the three main dimensions of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and reduced personal accomplishment.

Emotional exhaustion

A person suffering from burnout feels psychological and physiological pressure at all times. Facing the stress, anxiety, intense fatigue and/or insomnia that now form the pattern of their everyday life, the individual feels literally drained of their emotional resources.

Depersonalisation

Completely exhausted, the person decides to harden themselves to the world around them, protecting themselves from any affective load through depersonalisation. They come to consider others as objects or numbers rather than as human beings in their own right. In this way, they develop a lack of sensitivity, as well as a negative view of other people and of work in general. Depersonalisation (also known as cynicism) functions in a way as a self-defence mechanism, like a shell to protect the person from the outside world, which has become too painful.

Reduced personal accomplishment

Maslach and Jackson take personal accomplishment to mean notions of success and control over events. An individual suffering from burnout feels that they have no control over what happens to them: the situation is completely out of their hands. They feel unable to respond to the (unachievable) goals that they have often set for themselves. Eaten away at by a feeling of failure, frustration and discouragement, they feel that they are no good. Their self-image is at its lowest ebb.