Although many companies call upon motivated individuals in their job descriptions, motivation is not a skill that some of us have and some of us dont. It is a dynamic, a certain chemistry between an individual and the context they are in. Motivation is something that is cultivated, and whatever your job, your colleagues, your manager and your company all have their roles to play so that you are happy there. Although it is not always possible for you to act on other people and change their behaviour, we hope that an analysis of your situation in the light of the following ideas will motivate you to get stuck in again rather than doing nothing and letting the situation fester.

Motivation: the basics

Motivation, satisfaction or commitment?

Motivation is often confused with ideas of satisfaction and commitment. In their work Motiver, tre motiv et russir ensemble (Motivate, be motivated and succeed together), ric Cobut and Graldine Bomal explain that satisfaction is usually about the impressions we have about our professional situation, whereas motivation is more to do with the driving force behind our behaviour. Satisfaction is a state of being (we are either satisfied or unsatisfied), whereas motivation is a dynamic, a process requiring effort to propel us in our professional context. When we are motivated, it is always in reference to something; there is no such thing as absolute motivation. These two authors distinguish the absence of motivation from demotivation. There is in fact a subtle difference between not finding anything that makes you want to work hard and watching your desire to work hard disappear on account of the deterioration of your relationship to your working environment.

Commitment is another concept that can be confused with motivation. This concept mostly refers to the relationship the person has with the organisation and its members. Commitment corresponds to our degree of psychological identification with our work and influences our overall image. As various studies on commitment in organisations illustrate, including that of Howard Klein, Thomas Becker and John Meyer, there are different kinds of commitment:

- Commitment to work, which is linked to the space it takes up in our lives;

- Commitment to the organisation as a whole, which implies an alignment with its goals and values, a desire to make an effort for its benefit and a desire to remain part of it;

- Commitment to a career or profession;

- Commitment to a specific role (job involvement).

Your job and professional relationship with the organisation thus influence the perception you have of your overall image as well as your motivation at work. If you are being negatively impacted by elements of your professional context, it is important to spend a moment reflecting in order to figure out where the shoe pinches.

Evolution of the concept of motivation

In her work on intuitive management, Meryem Le Saget informs us that there have been three generations of conceptions of motivation since the early 20th century.

I get my tasks done

The first generation is linked to the age of industrialisation, efficiency and productivity, offering a single interpretation for workers, with identical solutions for each of them. Here, being motivated means working out of fear of an employer, out of hope for obtaining better living conditions, or for earning enough money to feed a family.

I contribute to the completion of work

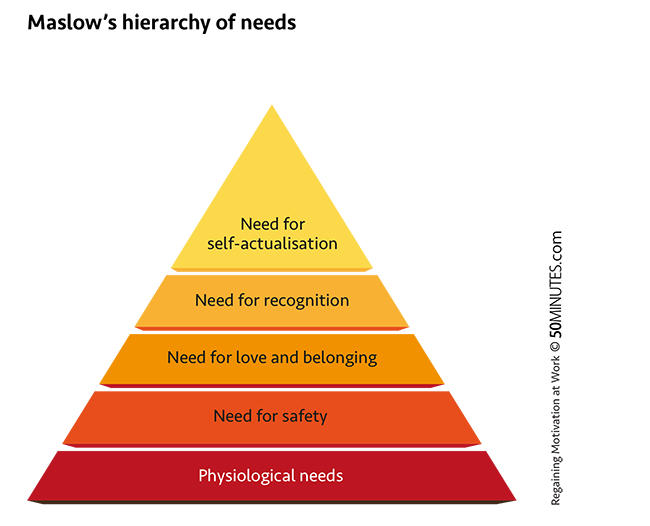

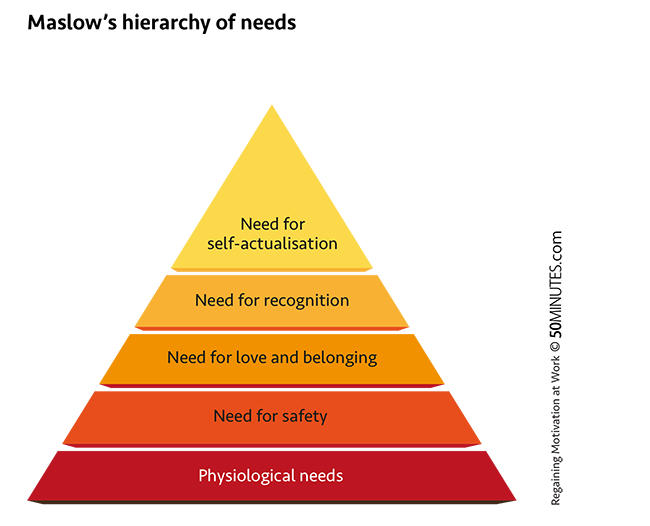

The second generation is aware of the concepts of satisfaction and dissatisfaction at work. The needs of employees are taken into account and are grouped into large hierarchical categories, as the satisfaction of the lower levels is necessary for access to the higher levels. This new generation understands that a motivated person, in order to stay motivated, needs to be listened to, needs a suitable position and needs their contributions to be recognised.

It was between 1950 and 1990, thanks to the human relations movement (a movement associated with the study of organisations following the Wall Street Crash of 1929, which studies group dynamics at work), that theories such as Maslows started to promote the idea that not everyone has identical motivations.

Among other authors, the American psychologist Frederick Irving Herzberg (1923-2000) completes this approach with his two-factor theory, suggesting that we should pay attention to the balance between the presence and absence of factors of satisfaction and dissatisfaction. In fact, according to him, factors of satisfaction act independently of factors of dissatisfaction. Thus, if the absence of occupational hygiene factors (salary, good relationships, good working conditions, etc. occupational hygiene actually concerns all the factors that affect the workers health and wellbeing) leads to demotivation, the presence of motivating factors (return as a result of invested effort, nature of work, recognition, independence, etc.) will not necessarily prevent the worker from feeling dissatisfied in their work. This generation is about promoting the satisfying aspects while simultaneously working to reduce the factors of dissatisfaction. If an employer wants to motivate their staff, they must take their employees needs into account, become aware of the factors of satisfaction and dissatisfaction and adapt solutions to the different scenarios.

I commit to my work because I can express myself and be fulfilled

Third-generation motivation appeared in the 1990s. Managers become leaders who are intuitive to systematic interpretations, and are committed to giving meaning back to work and treating people like adults. Beyond large categories, everyone is individual and solutions must therefore be tailored, but able to integrate into a complex system. It is no longer the task which is at the heart of motivation, but the interest in doing it.

Although the 1990s heralded the arrival of intuitive management, not all managers evolved at the same pace as the concept. It is not rare to observe managerial approaches that are centred on the division of tasks and the organisation of work, or based on participative management without having the slightest idea of what intuitive management might mean, the latter being based on the trust capital of their relationship with their employee and focused on the search for meaning in work.