Dane Anthony Morrison - Salem: Place, Myth, and Memory

Here you can read online Dane Anthony Morrison - Salem: Place, Myth, and Memory full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Northeastern University Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Salem: Place, Myth, and Memory

- Author:

- Publisher:Northeastern University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Salem: Place, Myth, and Memory: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Salem: Place, Myth, and Memory" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A superb collection of essays on Salems rich history and cultural life over the past four centuries

Salem: Place, Myth, and Memory — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Salem: Place, Myth, and Memory" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Acknowledgments

This book on Salem draws on the contributions of many people. The fourteen contributors, including photographer Kim Mimnaugh, who accepted the challenge of interpreting one place across time took especial pains to study Salem afresh and to think deeply about what this place has meant to each generation. In addition, many other people and organizations supported this project, and we wish to express our thanks to the following: John Acres, John Adams, Lisa Adams, the American Philosophical Society, Brad Austin, LaGina Austin, Emerson Baker, Barbara Baldassarre, Alice Bianchi, Asenath Blake, Patricia Buchanan, Deborah Burkinshaw, the City of Salem, Kristena Cowles, Elaine Cruddas, Donald Cutler, Alison DAmato, Destination Salem, Phyllis Deutsch, Thomas Doherty, Susan Edwards, Marc Glasser, Amie Marks Goodwin, Bob Gormley, John Hampsey, Nancy Harrington, Harvard University's Center for the Study of World Religions, Johannah Henson, Historic Salem, Inc., the staff of the House of the Seven Gables, Chris Idzek, Elizabeth Kenney, Rod Kessler, Alexandros Kyrou, Diane Lapkin, Will LeMoy, Gregory Liakos, Carolyn Lusignan, Henry Lusignan, Cynthia McGurren, Martha Jane Moreland, Anne Marie Nicholas, Robert Orsi, the Peabody Essex Museum, Phillips Library, Michelle Pierce, Arthur Riss, the Salem Athenaeum, the Salem Maritime National Historic Site, Jackson Schultz, Jackson Schultz III, Jonas Schultz, Anita Shea, the Society of the Cincinnati, Jim Stoll, Adam Sweeting, Carol Thistle, Margaret Vaughn, Donna Vinson, the Yellow Dog Caf, Peter Walker, Michael Weber, John Weingartner, and Patricia Zaido. Special thanks to Patricia Maguire Meservey.

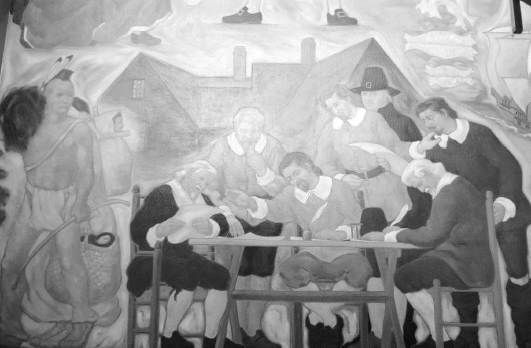

Puritans and Naumkeag Indians. Campus mural, Salem State College. Photo by Kim Mimnaugh.

Chapter One

Salem as Frontier Outpost

EMERSON W. BAKER II

... the pavements of the Main-street must be laid over the red mans grave.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, Main-street

EFORE there was Salem, there was Naumkeag. The Native American name, from the ancient Algonkian language, translates as the fishing place and explains why, for centuries before the arrival of English settlers, Native American peoples set their villages along the harbor. Overlooking Massachusetts Bay, reed-thatched weetos, or wigwams, nestled within a ring of wooden palisade fencing. Lazy smoke drifted upward through openings at the tops of these traditional native homes, and wafted over the sparkling waters. It was to the fishing place at Naumkeag that the first wave of English settlers came to plant their Puritan village in 1626. They christened it Salem, after the Old Testament city of peace, a condition they hoped to find in a New World that would be safe from the harassing policies of their king and church.

EFORE there was Salem, there was Naumkeag. The Native American name, from the ancient Algonkian language, translates as the fishing place and explains why, for centuries before the arrival of English settlers, Native American peoples set their villages along the harbor. Overlooking Massachusetts Bay, reed-thatched weetos, or wigwams, nestled within a ring of wooden palisade fencing. Lazy smoke drifted upward through openings at the tops of these traditional native homes, and wafted over the sparkling waters. It was to the fishing place at Naumkeag that the first wave of English settlers came to plant their Puritan village in 1626. They christened it Salem, after the Old Testament city of peace, a condition they hoped to find in a New World that would be safe from the harassing policies of their king and church.

Puritan Salem began as an outpost on the margins of the English world. It was the original settlement of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It was, as well, a borderlanda place of negotiation and accommodation between English and Native American cultures. In time, Salem would come to be known as a bustling cosmopolitan port with a substantial hinterland and numerous overseas trading spheres. It is difficult for us to imagine this community as contested ground, yet in the first half of the seventeenth century, Salem was such a placea frontier in which natives and pioneers struggled for control. The geographic reality of Naumkeags rich resources influenced seventeenth-century Salem profoundly and echoes throughout the subsequent history of the town.

Naumkeag, Native American Homeland

For modern readers, Naumkeag and Salem are just two names for the same place. For seventeenth-century Algonkians, however, the names invoked much more. To them, Salem was a name imposed on the place by newcomers. They were told the name meant peace in Hebrew and expressed the newcomers intention to build a community that would be devout in spirit and in harmony with their neighborsalthough the Puritans armor and blunderbusses may have raised some skepticism. The name Naumkeag carried no such ideological connotations. Instead, the fishing place was a practical description of a harbor and river that provided the bounty important for the Algonkians survival. It was the name given by their ancestors, who had occupied the land for generations and who even called themselves the Naumkeag to express their integration into this place. Furthermore, the Naumkeag extended the meaning of the name to encompass a tribal territory that occupied much of the coastal north shore of Massachusetts Bay. So, while Naumkeag was a distinct location, the word also referred to a people and to their larger homeland. Existing side by side during the 1620s, these namesNaumkeag and Salemimplied to Native American and English inhabitants the collision of cultures that would necessarily come about in a contested space. As the history of this place unfolded, the Native American inhabitants may have begun to recognize the irony that the founding of a city named for peace would result in so much death and misery.

The renaming of Naumkeag is an example of what can be called an imperialism of the map. English settlers and explorers very quickly renamed the landscape of New England, to give it a more familiar feel, to promote the region to potential settlers and financial backers, and to make a clear statement of their possession of the land. John Smith had begun this process in 1616 when he created his map of New England. Smith knew the Native American place names, but he renamed these locations after English towns and citizens. Naumkeag became Smiths Bristol. Although this name, like most of Smiths labels, did not stick, the English continued to rename and thus affirm their ownership of the region.

The names Salem and Naumkeag carry additional layers of meaning for the modern historian who researches through dusty documents to gain an understanding of different peoples sense of place and of the significance of toponomythe meanings of place names. An examination of surviving seventeenth-century court records and other legal documents reveals the complete English takeover of Salems toponomy. We discover that English colonists very quickly imposed familiar English names on landscape features such as rivers and ponds, replacing existing Native American terms. Naumkeag River became Bass River, and Mashabequa River became Forest River. Only a handful of Native American names survived long enough even to be written down by the colonists. Furthermore,

Because of this imperialism of the map, it is difficult to imagine that just a few years before explorer John Smith described Naumkeag, the fishing place, as a substantial and prosperous Native American community, occupied by a multitude of people.

The Pawtucket recognized no supreme sachem (chief) but divided themselves into regional groups under individual ruling families. From the accounts of early explorers such as Samuel de Champlain and John Smith, it is clear that the Pawtucket occupied a series of densely populated farming communities along the harbors and rivers of the region. There were three major groups of Pawtucket within Massachusettsthe Naumkeag, who occupied the lands from Salem to the Mystic River, the Agawam of Ipswich and northern Essex County, and the Pennacook, who occupied the Merrimac River. These various groups were affiliated through kinship, trade, and military alliance.

Because Naumkeag was unusually abundant in natural resources, the people were able to survive comfortably by moving from place to place. One strategy for growing their traditional crops of corn, beans, and squashquite different from English farming practiceinvolved cycles of slash-and-burn farming in which fields were quickly cleared, planted, and abandoned. Because they did not fertilize the fields, when crop yields began to drop a village would move a few miles to another location where the soil was more fertile. Another strategy was to move with the seasons, taking advantage of a bounty of natural resources. They fished from the ocean and rivers, hunted for game and wildfowl, and gathered roots, nuts, and berries. But despite the Naumkeags mobility, they were tied closely to their homeland. They believed they had occupied it since the beginning of time and it was the sacred resting place of their ancestors. They were intimately acquainted with each stream, marsh, and hill, and all the animals were imbued with Manitou, or spirit power. Thus the land did not just provide food and shelter to the Naumkeag; it was linked to their heritage and even their cosmology.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Salem: Place, Myth, and Memory»

Look at similar books to Salem: Place, Myth, and Memory. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Salem: Place, Myth, and Memory and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.