The translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften InternationalTranslation Funding for Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Office, the collecting society VG WORT, and the German Publishers & Booksellers Association.

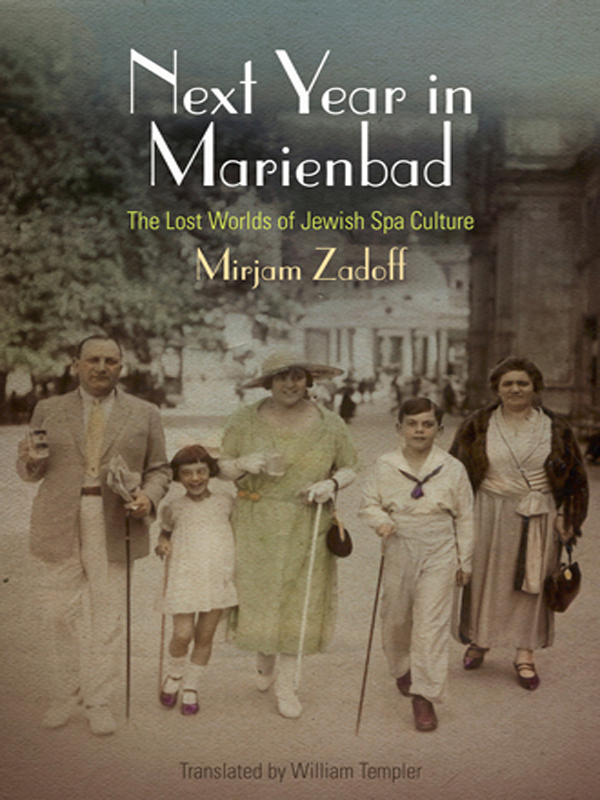

Originally published as Nchstes Jahr in Marienbad by Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. Copyright 2007 Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG

English translation copyright 2012 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A Cataloging-in-Publication record is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8122-4466-3

For Noam and Amos

Renault: And what in heaven's name brought you to Casablanca?

Rick: My health. I came to Casablanca for the waters.

Renault: Waters? What waters? We're in the desert.

Rick: I was misinformed.

Casablanca, Michael Curtiz (director), Julius J. and Philip G. Epstein, Howard Koch (screenplay), 1942

Culture is a book with a red cover. Astonished and opening it up, you ask what kind of book this is. Do you believe it is the Bible that everyone travels with? No, my friend, culture is Baedeker.

Gershom Scholem, Diaries, 17 August 1914

Introduction

The (Mirrored) Playroom

Departing for Paradise

But oh, Kitty! Now we come to the passage. You can just see a little peep of the passage in Looking-glass House, if you leave the door of our drawing-room open: and it's very like our passage as far as you can see, only you know it may be quite different on beyond.

Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1872)

So Isaac lay and looked at the firmament. And since the stars that illuminate the sea are the same stars that illuminate the land, he looked at them, and thought of his hometown, for it is the way of the stars to lead the thoughts of a person as they are wont. About the same time elsewhere in Eastern Europe, in the world that Yitzchak Kummer had left behind, there was another fictional departure. In his Yiddish novel The Brothers Ashkenazi, Israel J. Singer vividly describes a lively scene at the train station in the Russian industrial town of Lodz. As Chassidim, farmers, and emigrants crowd together in front of the third-class coaches of a train about to leave for the West, beside other, better coaches, the wealthier bestow flowers and sweets on their departing friends and family:

Before first-class and second-class wagons, well-dressed, self-assured passengers were gathered. Porters struggled under mounds of trunks, valises, hatboxes, traveling cases, and portmanteaux filled with enough dresses and accessories for two weeks at a fashionable resort. Dressed in their long gowns and huge plumed hats, the ladies minced along, conversing in German, even though they were still miles from the German border.

Fleeing the oppressive summer heat in Lodz, the prosperous Jewish middle class was, as every year, leaving for a stay at a spa in the West. In but two short generations, Singer's protagonists had climbed the social and economic ladder into the middle and upper classes of the city, although they still lived a largely Orthodox observant Jewish life. And so they traveled to a health resort that could offer a Jewish ambient and the necessary Jewish infrastructure. People gathered in the Austrian Kurort of Carlsbad.

In these two very different tales of departure, the western Bohemian watering place of Carlsbad embodied the image of a place of powerful attraction for European Jewry around 1900. Carlsbad and its nearby sister towns Marienbad and Franzensbad were a veritable mineral springs magnet, attracting the Jewish middle classes as well as Zionists and Chassidim; this even while others, as Singer commented with a touch of irony, had previously avoided the resort because it had become too Jewish.

In actual fact, during the summer season, an unusually large number of trains from Europe both East and West regularly stopped at Carlsbad Central Station. In the 1870s, the spa was connected up with the continental rail network, thus eliminating the need for the difficult journey by postal coach. As a result, the popularity of the spa soared, and with it the rapidly mounting number of visitors.

Figure 1. Carlsbad, Alte und Neue Wiese, 1900.

Once disembarked at the Carlsbad station, travelers had a short journey to the spa area, either by horse-drawn cab, sulky, omnibus, or on foot. Situated in a long, narrow valley on the Tepl River, surrounded by heavily wooded hills, the town greeted guests on arrival with a memorable cityscape: a dense assortment of historical promenades, lobbies, and monumental buildingsan exuberantly eclectic clutter, a multi-story, gaily colored rendezvous of the cream gteaux.

If the geographical space that was Carlsbad, situated snug in its narrow valley, presented one and the same vista of entry for all who arrived, extending from the station through the commercial center to the district of the spa, the historical place is multifaceted. It offers numerous channels of access. These lead into a literary space, an imagined place, a locality of nostalgic memory, a place of encounter, a site of illness and health, a habitat of pleasure and amusement, a feminine space, a Jewish place, a German place, a Czech one.

Of the possible channels of access, the present study focuses on the above-mentioned and widespread imagination of Carlsbad as a Jewish place, with different sides and protagonists, infused with connotations both positive and negative.

Summertime Topography

It's hard to write about Carlsbad. Not because there's nothing to talk about, but because there's just too much there.

Zevi Hirsch Wachsman, In land fun maharal un masarik

Every summer, a network of destinations promising recreation and recuperation were offered anew to an international middle-class spa public. An imaginary archipelago

Ever since the middle classes began in the last third of the nineteenth century to create a new form of mass spas, Jewish spa patrons had played a central role in the summertime experience as a key middle-class group. spa patrons and physicians, businessmen, and office workers who were resident there for the season. Over the years, this interaction generated functioning multifaceted Jewish networks and infrastructures.