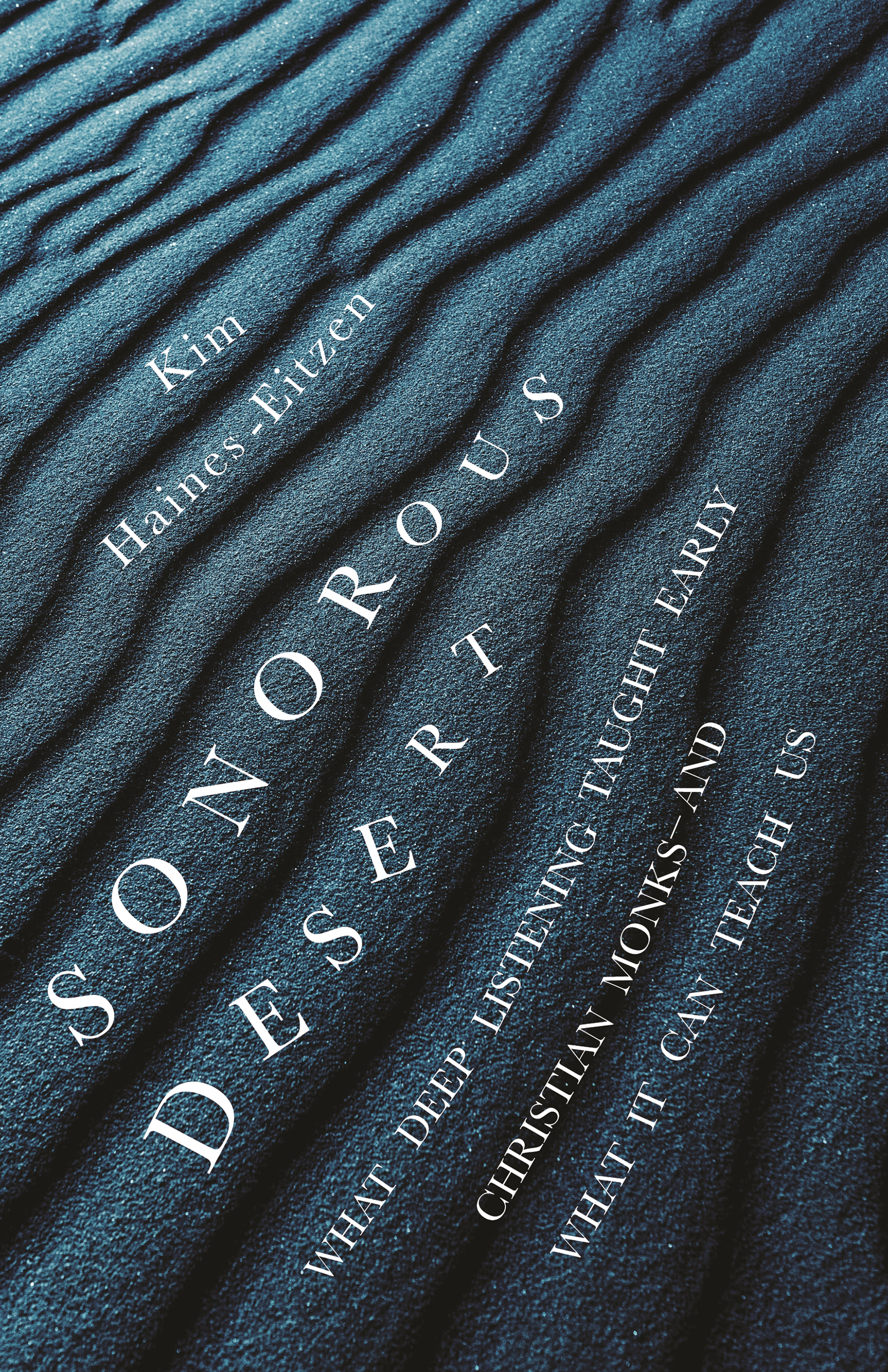

Sonorous Desert

Kim Haines-Eitzen

SONOROUS DESERT

What Deep Listening

Taught Early Christian Monksand What It Can Teach Us

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2022 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

99 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6JX

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Haines-Eitzen, Kim, author.

Title: Sonorous desert : what deep listening taught early Christian monks-and what it can teach us / Kim Haines-Eitzen.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021051264 (print) | LCCN 2021051265 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691232898 (acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780691237411 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: ListeningReligious aspectsChristianity. | Monastic and religious lifeHistoryEarly church, ca. 30600. | DesertsReligious aspectsChristianity. | SilenceReligious aspectsChristianity. | SolitudeReligious aspectsChristianity. | BISAC: RELIGION / Monasticism | RELIGION / Meditations

Classification: LCC BV4647.L56 H35 2022 (print) | LCC BV4647.L56 (ebook) | DDC 231.7dc23/eng/20211130

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021051264

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021051265

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Fred Appel and James Collier

Production Editorial: Natalie Baan

Text Design: Carmina Alvarez

Jacket Design: Layla Mac Rory

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: Kathryn Stevens and Maria Whelan

Copyeditor: Dana Henricks

Jacket image: Jonathan Borba from Pexels

To John, Eli, and Ben,

who enrich my listening life

immeasurably

And to my parents,

who set me on a listening path

from the beginning

Listening is a primary mode of understanding. As we listen to the world around us, we come to understand more deeply our place within it. Our listening animates the world. And the world listens back.

John Luther Adams,

The Place Where You Go to Listen

Contents

- xi

- xiii

- 1

- 23

- 41

- 59

- 75

- 93

- 109

- 123

Note to Readers and Listeners

Accompanying this book are recordings I have made in .

Ive also included a reading guide for monastic texts. The fact is that there was a rapidly growing literature about Christian beginning in the fourth century CE. In this book, I have drawn from the texts that speak most to the intersection of sound, desert, and monasticism, but they are only a small fraction of what is available. Although these texts were all written in languages other than English, I append a list of readily available English translations for those who wish to read the texts for themselves.

A Personal Prologue

In the course of writing this book, Ive been asked many times, usually by academic colleagues and friends, how I came to write about desert sounds and the ancient monastic quest for silence and solitude. They wonder how I, a historian of early Christianity and Judaism, could pivot from my earlier work on ancient scribes to a project about sound, hearing, and listening. The answer I have frequently given is that my work to this point has been focused on how the fact that most people couldnt read and write in the ancient world means we need to take sound and listening much more seriously in our understanding of the past. Most people in the ancient world heard the Bible, they didnt read it themselves; most people learned the stories of the ancient Greek and Roman gods by listening to stories or seeing them performed in the theatre, not by reading them. And the many ancient stories about the sounds of seduction (like the sirens who sing in Homers Odyssey), the sounds of war (like the sounds of trumpets used to launch battles), and the sounds of the apocalypse (again, trumpets, but also peals of thunder and the sound of sheer silence) reveal just how much sounds inspired the ancient imagination. In a predominantly oral world, hearing and listening mattered.

But the truth is that my research into desert sounds and early Christian desert monasticism has been as much a personal journey as it has been an academic one. When I reflect now on that questionthe question of how I turned toward themes of solitude, silence, nature, and the desertI realize that in some ways Ive been preparing to write this book my whole life. Seeds were sown in many places along the way.

None of us can remember the first sound we heard, for our ears and hearing develop while we are still in utero, beginning sometime around eighteen weeks. Six months before I was born, my mother fretted with my one-year-old sister inside our flat-roofed limestone home in the hills of Beit Jala, just to the south of Jerusalem, listening to the sounds of sirens and bombs in Jerusalem during the June war of 1967. My father had gone up the hill to watch from a rooftop as fighting unfolded.

My parents had moved to Jordan from Indiana the year before to study Arabic and to work with a humanitarian organization. They arrived full of hope and a commitment to service, instilled in them by their Mennonite backgrounds. Neither of them anticipated a war. I dont recall hearing the sounds my mother heard that June, of course, but I think somehow I learned something on a cellular level about sound and fear, place and identity, violence and belonging. I can only faintly imagine her fear, and the fear of so many women around the world, in a war-torn place. I began at an early age learning to listen, learning to keep quiet, learning to be watchful. A first seed, perhaps.

My mother likes to tell this story: when I was just a few months old, my parents drove from Beit Jala to Wadi Qilt, a historic canyon just east of Jerusalem, to visit the monastery of Saint George. She remembers how my father hiked up to the monastery, but she stayed in the cool shade at the base of the canyon, where the creek was flowing and the breeze moved through the trees, and I slept peacefully. So she says. I have returned to that monastery many times over the years, sometimes hiking the trails through the canyon. The research and writing of reminded me of my mothers story and enabled me to revisit a place Ive known since infancy.

In subsequent years growing up in Nazareth on a hospital compound, where my father worked as a chaplain, we marked time by the call of the mosques minaret five times a day, listened to the bells of the Basilica of Mary on Sundays, and knew where in town there were engagement parties or weddings, because the music resounded around the hills. We learned, too, the languages of Arabic and, later, Hebrew, adapting our ears and voices as needed. I listened closely to the doves and pigeons outside my window, knew when the gardener was working below by the sound of his reed flute, and, in 1973, heard the sirens that blared throughout the town during the Yom Kippur war. We listened to the sirens and took shelter in a cave dug into the limestone hill just across the road. It was quiet in there, the limestone flaking from the walls to the loamy floor. As a child, I thought it was somewhat festive, being interrupted from our dinner and needing to put our plates of food onto trays and walk across the street to the damp cavea cave that also had an altar and chapel tapestriesto join friends from the compound. But this is, Im sure, entirely too romantic a memory. The truth is sounds are often alarm calls and they can instill in us a visceral fear. We learn to keep safe by listening. And, sometimes, quiet is a comfort. The cool quiet of the forest behind the hospital compound, Kfar HaHoresh, was also a welcome respite from life (and death) at the hospital.