Closed Systems and Open Minds

Closed Systems and Open Minds

The Limits of Navety in Social Anthropology

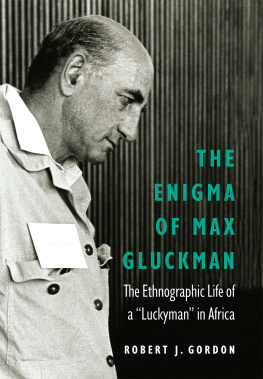

Edited By MAX GLUCKMAN

First published 1964 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1964, Max Gluckman, Ely Devons, V. W. Turner, F. G. Bailey, A. L. Epstein, Tom Lupton, Shiela Cunnison, William Watson.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2006049917

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Closed systems and open minds : the limits of navety in social anthropolpogy / Max Gluckman, editor.1st pbk. printing.

p. cm.

Originally published: Chicago : Aldine Pub. Co., 1964.

Essays written during the years 1957-58 by members at various times of

the Department of Social Anthropology and Sociology at the University of

ManchesterPref.

ISBN 0-202-30859-6 (alk. paper)

1. Sociology. 2. Anthropology. 3. Social psychology. 4. Social systems. I. Gluckman, Max, 1911-1975.

HM545.C56 2006

301dc22

2006049917

ISBN 13: 978-0-202-30859-3 (pbk)

This book consists of essays written during the years 1957-58 by members at various times of the Department of Social Anthropology and Sociology at the University of Manchester. The Department had agreed to present a series of papers on a common theme to a meeting of the Association of Social Anthropologists in Edinburgh in September 1957. The Association was at that time hoping to publish Memoirs covering its proceedings, and it planned that groups of members would prepare each Memoir. Research at Manchester had covered the study of African tribes and Indian villages in the traditional field of anthropology, but members of the Department had also studied factories, villages, and other fields of social relationship in Britain. Working in these diverse fields we became interested in the question of what was common in our methods and analyses, and how they were distinguished from and related to those of other social and human sciences. This question had been discussed with colleagues in other subjects in the Faculty of Economic and Social Studies, particularly with Professors Ely Devons in Economics, Dorothy Emmet in Philosophy, and W. J. M. Mackenzie in Government.

One of the issues which recurred in these discussions and was raised frequently by Devons was, what basic assumptions were implied by social anthropologists in their work? Another issue, related to this, was by what criteria social anthropologists decided how to limit the field of their studies? Naturally this led to argument about the effect of these assumptions and limitations on the significance of social anthropological analysis. The Department therefore decided to read papers to the Association meeting at Edinburgh dealing with these twin themes. The arguments were not in general or theoretically methodological terms, save for a brief introduction by Gluckman, but each contributing member of the Department analysed a recent piece of his research with these two issues in mind. At an early stage of the discussions, Gluckman suggested that social anthropologists were justified in making nave assumptions outside their own field of study: indeed they had a duty to be nave, but this navety would limit the conclusions that could be drawn from their analyses. It was decided, therefore, to make the limits of navety in social research the common theme of the Manchester contribution to the Edinburgh meeting.

The papers by Lupton and Cunnison, by Epstein, and by Watson, published here, were given at Edinburgh in 1957. We stress the date because Epsteins theory predicts later developments; and Watson puts forward a theory which has been independently put forward, at least in part, by later publications, such as Whytes The Organization Man (1957). Turners paper was presented at the following meeting of the Association of Social Anthropologists at University College, London, in March 1958.

The Association found it impossible to undertake the financial obligation of publishing Memoirs, and we decided to try to collect further papers around the main theme from present and former members of the Department and independently to publish these in a book. Bailey read his paper to a seminar late in 1958, but others who hoped to write articles on aspects of the problem which we wished to cover, were in the end not able to do so.

All the papers were discussed at seminars in Manchester, and Devons, who had been closely associated with the Department of Social Anthropology since its foundation at Manchester, attended most of these seminars. He agreed, though not an anthropologist, to join with Gluckman in writing a commentary on the essays and the problems in general. It became clear in discussion that the issues involved were important in other social sciences, and Devons, as an economist, stressed particularly the manner in which they affected economics. This accounts for the references to economics in the introductory and concluding chapters. But these chapters are concerned primarily with the problems which face social anthropologists, and the references to economics (like those to psycho-analysis) are included to emphasise that the issues discussed throughout the book are important in all social and behavioural sciences. In order to anticipate criticism we here state that the references to economics are included merely for this purpose: a full discussion of these problems in economics would require another book.

Writing the introductory and concluding chapters jointly raised a few difficulties. We have agreed throughout on the central methodological issues: indeed, it was this general agreement about problems of studying society, and about the nature of knowledge itself, which helped stimulate our interest in each others subjects at Manchester. We have worked out our own contribution to this book through long discussion and several written versions. Despite the fact that we brought to our task different expertise and experience, we never disagreed on methodological issues. We had to strive for clarity, not for accommodation. We did differ on a few occasions in our evaluation of specific hypotheses, and in our judgment on what material from outside the essays in this book we should use to illustrate our argument. Though we both believe that the problem arises in all sciences, we repeat that the book is about social anthropology; hence Gluckman selected for discussion the work that he considered had raised major problems for anthropologists. It would have been tedious for the reader had we tried to denote any difference in emphasis that Devons would have placed on these problems, and we have therefore throughout used the phrasing, We....