Classic

Anthropology

Other Books by John W. Bennett

Human Ecology as Human Behavior:

Essays in Environmental and Development Anthropology, 1993, 1995.

Settling the Canadian-American West:

Pioneer Adaptation and Community Building (with Seena B. Kohl), 1995.

Of Time and the Enterprise:

North American Family Farm Management in a Context

Of Resource Marginality, 1982.

Northern Plainsmen: Adaptive Strategy and Agrarian Life, 1969.

Hutterian Bretheren:

The Agricultural Economy and Social Organization Of a

Communal People, 1967.

Paternalism in the Japanese Economy:

Anthropological Studies Of Oyabun-Kobun

Patterns (with Iwao Ishino), 1963.

In Search Of Identity:

The Japanese Overseas Scholar in America and Japan

(with H. Passin and R.K. McKnought), 1958.

Archaeological Explorations in Jo Daviess County, Illinois, 1945.

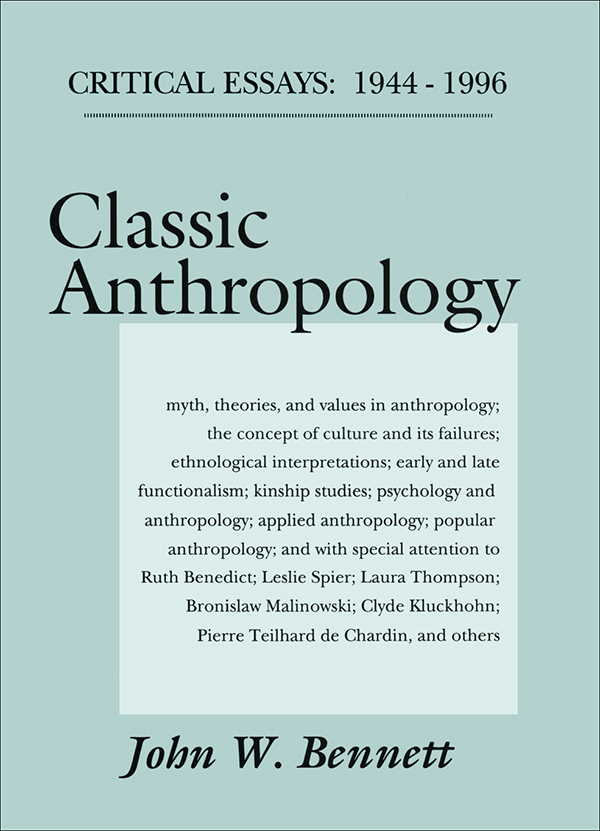

CRITICAL ESSAYS: 1944 - 1996

Classic

Anthropology

John W. Bennett

with contributions

by Leo A. Despres

and Michio Nagai

First published 1998 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 ThirdAvenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Copyright 1998 by Taylor & Francis

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 97-45618

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bennett, John William, 1915-

Classic anthropology : critical essays, 1944-1996 / John W.

Bennett with contributions by Leo A. Despres and Michio Nagai.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Anthropology. I. Despres, Leo A. II. Nagai, Michio.

III. Title.

GN25.B46 1998

301dc21

97-45618

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-1-56000-333-5 (hbk)

I would like to dedicate this book to the memory of the three Classic anthropologists whose work had the most influence on my early thinking and research:

Robert Redfield

W. Lloyd Warner

Clyde Kluckhohn

Contents

With an Epilogue concerning

With a Supplement: A Review of Subsequent Researches on the Sun Dance

With Two Supplements:

1. Letters Received after Publication of Article

2. A Review of Subsequent Studies of Pueblo Culture and Behavior

With a Supplement: Some Subsequent Studies of Witchcraft with Special Reference to Attempts to Distinguish between Social, Cultural, and Psychological Phenomena

(co-authored with Leo A. Despres) With an Epilogue, 1996

With a Supplement: The Career of Sol Tax and the Genesis of Action Anthropology

With a Supplement: A Note on the Critique of Benedicts Chrysanthemum and the Sword by Japanese Scholars (co-authored with Michio Nagai)

Tables and Figures

In 19941 thought it was about time to compile a bibliography of my writings, and in the course of that effort I reread a number of my earliest articles and essays on sociocultural anthropology, plus various associated correspondence and notes. I was struck by the fact that some of the pieces fell into a rough developmental sequence from the early 1920s to the 1950snot that I was actually writing in the 1920s but beginning in the early 1940s I produced a number of essays about theories and methods covering a time period from the 1910s to the 1950s. This gave me an idea: if I could supplement these older pieces with additional essays I would have a kind of personal intellectual history of the era. And the dates I eventually selectedfrom 1915 to 1955seemed to cover the period of classic efflorescence of anthropology in the twentieth century. Why not give it a name? The term Classic anthropology era came to mind, since much of the work produced during that period seems to be regarded as the most typical or perhaps the finest the discipline ever produced. The nature of the previously published pieces established the approach of the book: it could not be a formal history of the era and its works, on the order of Lowies 1937 masterpiece, nor a blockbuster compendium like Harriss 1968 volume. It would have to consist of a series of analytical essays on particularly important works and ideas that shaped the intellectual outlook of the eraor at least, my outlook.

Now, the trouble with a collection of essays is the difficulty of maintaining continuity and thematic integrity. In order to assist the reader in his effort to find some unity, I supply the following comments: first, the essays contain a running commentary on the concept of culturethat concept which represents the dominant idea in Classic anthropologyat least in the United States. I develop two principal criticisms: first, the concept always seemed to me to have little relevance as a tool for explaining the world around us. For example, in my on populist anthropology, each author of the three books discussed, after pages of archaeology and ethnology, winds up with devastating criticisms of contemporary society and world affairs hardly a word of which can be traced back to the anthropological concepts or research described earlier. It was also my early conviction that the anthropologists of the era never fully understood the consequences of using a second-order abstractiona collective nounto explain or interpret the nature of human behavior.

Second, anthropology during this era was dependent on data from tribal societiesthat is, relatively isolated folk cultures, mostly removed from modern urban-industrial civilization, although influenced by it. This specialized data inhibited the disciplines ability to comprehend the nature of modern culture as it had began in the eighteenth century in Europe. But at the same time, anthropologists insisted on interpreting modern life as if their specialized concepts and data had prepared them for the task!

Third, some of my essays comment on the moral ambiguity of anthropologys attempt to report on and understand people who were actually vulnerable to exploitationand possibly even made so by the reportage produced by ethnologists. Correlated is the peculiar resistance shown by academic anthropologists to applied social science (see ). I suspect this was due not only to scholarly arrogance, but also to a fear that such work might expose the moral shortcomings of the discipline. And these, of course, also were related to the prevailing relativism of anthropologys methodological and theoretical posture.