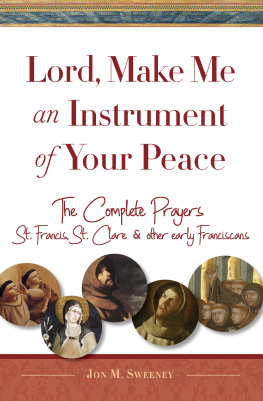

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.

Where there is hatred let me sow love,

Where there is injury let me sow pardon,

Where there is doubt, faith,

Where there is despair, hope,

Where there is darkness, light,

And where there is sadness, joy.

I NTRODUCTION

The Sunlight of God

When we try to understand God, we are like children trying to hold sunlight in our hands. We recognize the presence of something ineffable and mysterious, but always it eludes our grasp.

Thus it has always been, and thus it will always be. We know that, at heart, all great spiritual truths contain an utter simplicity, a shimmering depth of meaning that eludes definition and gives life a unity that no amount of analysis or knowledge can ever attain. But when we try to grasp that simplicity, we are always found wanting. We are left with the stone tablets, though we dream of being touched by the hand that gave them.

Over time we build great cathedrals of meaning and call them theology. They are brilliant monuments crafted by our intellect, worthy expressions of the best that we can do to approach the majesty and mystery of God through the mind. But ultimately they, too, are creations of stone. They may get us closer to the ways of God on earth, but they bring us no closer to his presence.

Occasionally, in every tradition, a work emerges that seems to give us a glimpse of that presence. It seems to come from the very heart of God and to contain the mystery and majesty that we so longingly seek. It is so clear, so simple, so direct and unassailable in its spiritual truth that it transcends analysis and understanding. It is the sunlight that animates the cathedral of our theology, the touch of the hand that brings the tablets of stone.

The Prayer of Saint Francis is such a work. It shines through all the contradictions and illuminates the way of the spirit like a light from the heart of God. It asks nothing of us that we cannot do, yet it commands the impossible. It is a mighty shout from a mountaintop and a quiet entreaty whispered with bowed head. It is profoundly and decidedly Christian yet irrefutably and fundamentally universal. It is a gentle hand guiding us along the long and difficult pathway to God.

Ours is a time when people of good faith yearn for such guidance. We want to be able to walk in the way of God without closing ourselves off to the ways of others.

The Prayer of Saint Francis allows us to do so. It gives voice to our faith without asking us to turn our backs on those who have chosen other paths. It is so pure, so human, so universal in its expression, that no good-hearted person of any faith would stand against it.

There is a story told by some of the Native American peoples about the stars in the midnight sky. Each star, they say, is a hole pierced in the veil of heaven by souls that have died, and the light that shines through is the light of God, the Great Spirit, the Great Mystery.

In such a sky, Francis must be one of the brightest stars, for no one has given us more of the light of God than he. Through his life, his works, and the legacy of his joyous faith, he seems to illuminate the very center of the human heart. And nowhere does he do this more beautifully than in his gentle prayer Lord make me an instrument of your peace.

In this beautiful and gentle prayer, he touches our deepest humanity and ignites the spark of our divinity. He makes the pathway clear, makes the stones come alive. In these few simple words, Francis places Gods sunlight in our hands.

T his morning I was awakened by the trilling of a single bird. It burst like sunlight into the lambent darkness, so sweet and pure as to seem to be the first sound ever heard in all creation.

I walked to the window to listen. The bird, unaware, continued its solitary anthem. The breeze had stilled; the night rustling had subsided. Peace lay over everything. It was as if I was present at the dawn of time.

Slowly the day began to wake. Light limned the distant horizon, turning the edges of the sky to lavender. The trees began to move with the gentle breathing of the wind. All around me life was stirring. But above it all, the single voice of the solitary bird sang out in celebration of the day.

As the light grew, other sounds began. The rustle of the branches, the bark of a dog, animals scurrying, people beginning their day. And as the sounds of daily life layered across the sunrise, the bird fell silent. It had played its part. Now it gave way to other, louder voices. Its song disappeared into the music of the morning.

Such a Franciscan vision, and how close to the first line of Franciss gentle prayer, Lord make me an instrument of your peace. It was as if the bird was offering up its own canticle to the sun, and I alone was blessed to be present to hear.

I thought of an image a teacher had once offered me. God, he said, is like a great symphony in which we must all play our individual parts. None of us can hear the whole; none of us is suited to play all the parts. We must be willing to accept the limitations of the instrument we have been given and to offer up our voice as part of the great and unimaginable creation that is the voice of God.

This bird, from the fullness of its being, was offering up its voice into that creation. I felt humbled and awed to have been in its presence.

Francis, more than any other saint, understood the godliness of music. He sang constantly. His prayers are filled with entreaties to sing to the Lord a new song and petitions for the earth to sing out to the Lord in praise. He was even said to stop often in the middle of a road, pick up a stick, and mimic the playing of a violin while he sang. It is as if prayer itself was song for Francis, and life itself was prayer.

Imagine what music must have been in his time. In a world with no machines, none of the background noise of modern life, and no way to capture the elusive and ethereal tones of music other than to hear them when they were created, it must have been a miraculous thing indeed to hear a sound, sonorous and haunting, created by the breath or the plucking of strings. It would rise up, like birds in flight, and float above the dross of the days, like the very voice of God itself.

What more hallowed object could have existed in such a world than something crafted by the skilled hand that could create such sounds and turn breath or touch into melody? To play an instrument would have been a divine skill. To be an instrument would have been a sacred thing indeed.

When Francis asks to be made an instrument of Gods peace, he is bowing down before Gods skill as maker, as musician, as composer of our days, and offering himself up to be shaped into a form through which the voice of God can be heard.

When we give ourselves to his prayer, we are asking the same.

I once had a conversation with a woman while I was on a train traveling across Canada. She was a musiciana violinistwho, as a child, had performed with major symphonies in America and Europe. She had been a prodigy, one of those rare individuals who seems to have a talent that comes from somewhere far beyond the realm of normal human affairs.