Michael Gellert - Modern Mysticism: Jung, Zen and the Still Good Hand of God

Here you can read online Michael Gellert - Modern Mysticism: Jung, Zen and the Still Good Hand of God full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1994, publisher: Nicolas-Hays, Inc, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Modern Mysticism: Jung, Zen and the Still Good Hand of God

- Author:

- Publisher:Nicolas-Hays, Inc

- Genre:

- Year:1994

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Modern Mysticism: Jung, Zen and the Still Good Hand of God: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Modern Mysticism: Jung, Zen and the Still Good Hand of God" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Gellert takes us on a moving journey to explain modern mysticism and the highest religious experience.

Modern Mysticism: Jung, Zen and the Still Good Hand of God — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Modern Mysticism: Jung, Zen and the Still Good Hand of God" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

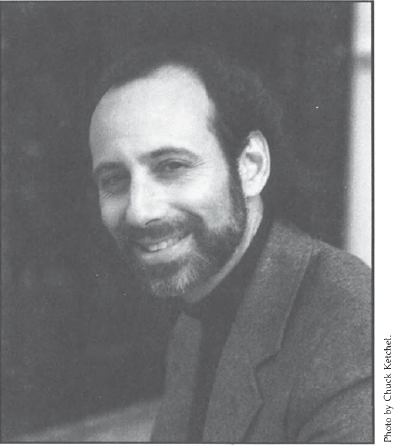

Michael Gellert has Master's degrees in religious studies and social work. He has studied with Marshall McLuhan at the University of Toronto, and undertook Zen training with the Zen master Koun Yamada in Japan. He has worked and traveled extensively in Asia. Mr. Gellert has taught psychology and religion at Vanier College (Montreal), Hunter College of the City University of New York, and the College of New Rochelle. He was Coordinator of District Council 37's Personal Service Unit Outreach Program, an employee assistance program for the City of New York. He is currently a psychotherapist in private practice in Santa Monica, California, and is in the Analyst Training Program of the C.G. Jung Institute of Los Angeles.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people have shared in the making of this book. Gary Granger, with whom I have enjoyed a spiritual comraderie for twenty years, contributed much time, critical reflection, and valuable insight, helping to elucidate some of the book's more difficult ideas. Also integral was George Gellert: he was always a source of encouragement, a wellspring of constructive suggestions, and a brother in the truest sense of the meaning. And Betty Lundsted, my publisher and editor, applied her wise discretion in details great and small, significantly influencing the book's discussion and helping to refine it into its present form.

I am particularly grateful to Susan Engel for introducing me to the Ann and Erlo van Waveren Foundation, and for providing other valuable assistance just when it was needed. To the Ann and Erlo van Waveren Foundation itself, I am most indebted. With its strong commitment to research in depth psychology and its generous fellowship, it was a source of both moral and financial support. And a word of deep appreciation goes to Dr. Aryeh Maidenbaum: he too was a steady source of encouragement and insight, and was helpful in more ways than he probably imagines.

Julie Mendlowitz, my loving companion through much of the book's creation, deserves heartfelt thanks for being very supportive and understanding about the demands placed upon my time. Alvin Muckley, Elizabeth Czerwinska, Susan Hochberg, and Lorraine Altman were also always ready to lend their listening ears and offer good cheer. For their very special ways of listening and dialoguing, I wish to acknowledge Nicole Corey, Dr. John Clark III, and Maggie Weintraub. And for contributing ideas that have enhanced the presentation of the text, I would like to thank Jerry Mendlowitz, David Deneau, Lucy Lentini, Natassia Cole, and Andy Sos.

There are other people who have touched my life in one way or another over the years, and though they did not contribute directly to the research or writing process, they helped me arrive at a place where I could sit down and write this book. They include Rabbi Izidor Lorincz, Dr. Paul Kugler, the late Koun Yamada-roshi, Barbara Sicherman, Dr. Paul Babarik, Brahm and Carole Canzer, Norman and Harriet Weinstein, and all my colleagues from District Council 37. The other friends and teachers who have helped in this way are too many to mention here, but I am sure they know who they are and how appreciative I am.

And finally, I wish to express my gratitude to some others who have provided material for this book. Lewis Freedman graciously made available his recorded interviews with Ingmar Bergman; Reynold Miller, Victor T., and Ellen S. shared personal experiences; the estate of General George Patton kindly gave me permission to quote from General Patton's poetry; and Random House let me use an excerpt from Composition of Thus Spake Zarathustra in Friedrich Nietzsche's Ecce Homo and The Birth of Tragedy, translated by Clifton P. Fadiman. Other authors to whom acknowledgements are due are: Donald Keene, for a quotation from his translation of the Japanese Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves (Man'ysh); Raymond B. Blakney, for a passage from his Meister Eckhart: A Modern Translation, published by Harper & Row, 1941 (fragment 37, p. 246); and Osbert Moore, for an excerpt from A Thinker's Notebook.

APPENDIX

THE DREAM JOURNAL

This is a Jungian method for keeping a dream journal. It of course does not include all the Jungian and other ways of working with dreams. What it provides are Jung's basic ways of exploring dreams.

The journal itself should be a notebook large enough to contain a lengthy period of entries. Like in any journal, the entries should be dated, as you may wish to reread them at a later time. Indeed, reviewing the journal periodically is a vital part of dream work. Often the significance of a dream only becomes fully apparent when it is seen in context of other dreams from the same period or even another period. The psyche does not necessarily unfold linearly. Also, by periodically reviewing the journal and seeing shifts in recurring themes and situations, and with recurring symbols (people, animals, etc.), you can get a sense of the direction the psyche is moving in. Of course, very important to this will be the changes you make in your actual life in response to what you learn from your dreams. The dream journal thus becomes a kind of diary or autobiography, but an autobiography of the unconscious as much as of yourself.

Every dream entry should have five parts. They are as follows:

1. Dream: This section is an exact description of the dream, how you felt in it, and its mood. It should not include conscious associations, but just the facts. If you know that you have forgotten certain parts, you may indicate this so that you know where something is missing.

2. Associations: This section and those that follow consist of the conscious work that you do with the dream, and so they should be undertaken in a deliberate way and obviously not in the middle of the night. Without these sections, the dream's meanings remain unconscious, and it is as if the dream never happened. In this section you go through the dream part by part and write out all your conscious associations, to each event, place, and situation, and to each person, animal, creature, and object of importance. You may here associate the dream to something going on in your life, asking yourself what the dream is trying to tell you, or what it in turn is trying to ask you.

This is a tricky part of the dream work, for often we think we have arrived at a dream's meaning from our associations when in fact our associations are often part of the problem that the dream may be commenting on. As Jung said, our problems are revealed by our associations, and not solved by them. The reason for this is that our associations come from the ego, and not the unconscious or the Self. Our ego and its attitudes are our blind spot, and are personified in the dream by ourselves, by the dream ego. Hillman captured this problem when he said that everything in a dream is exactly the way it should be, except the ego. This problem of the ego's blind spot is also why both Freud and Jung felt that to analyze one's dreams optimally, one needs another personpreferably a trained therapist or analystto act as a mirror that reflects one back to oneself more objectively. In the final analysis, our associations to a dream give us a clue, and not necessarily the dream's message.

3. Active Imagination: This is Jung's technique for making a dream's meaning conscious. It is also a kind of meditation. One form of it is to imagine the dream continuing from where it left off. You review the dream, sink into it as if it is reoccurring, and then continue it to where you imagine it might have gone had it not ended where it did.

Another form is to pick a character in the dream other than the dream ego and write out a dialogue with it. The character may be a central character, but sometimes a seemingly peripheral character in a dream may hold the key to it. The character may also be nonhuman, that is, an animal, a tree, or any other magical creature or object. Active imagination is a process of the imagination, and as with dreams, anything is possible.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Modern Mysticism: Jung, Zen and the Still Good Hand of God»

Look at similar books to Modern Mysticism: Jung, Zen and the Still Good Hand of God. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Modern Mysticism: Jung, Zen and the Still Good Hand of God and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.