Table of Contents

Published 1998 by Prometheus Books

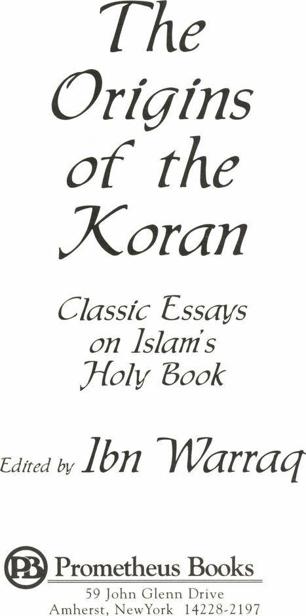

The Origins of the Koran: Classic Essays on Islams Holy Book. Copyright 1998 by Ibn Warraq. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Inquiries should be addressed to Prometheus Books, 59 John Glenn Drive, Amherst, New York 14228-2197, 716-691-0133. FAX: 716-691-0137.

02 01 00 99 98 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The origins of the Koran : classic essays on Islams holy book /edited by Ibn Warraq. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 1-57392-198-X (alk. paper)

1. KoranHistory. I. Ibn Warraq.

BP131.074 1998

297.1221-dc21

98-6075

CIP

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

PART ONE

Introduction

Introduction

Ibn Warraq

T HE STEREOTYPIC IMAGE OF THE Muslim holy warrior with a sword in one hand and the Koran in the other would only be plausible if he was left-handed, since no devout Muslim should or would touch a Koran with his left hand which is reserved for dirty chores. All Muslims revere the Koran with a reverence that borders on bibliolatry and superstition. It is, as Guillaume remarked, the holy of holies. It must never rest beneath other books, but always on top of them, one must never drink or smoke when it is being read aloud, and it must be listened to in silence. It is a talisman against disease and disaster.

In some Westerners it engenders other emotions. For Gibbon it was an incoherent rhapsody of fable,

For us in studying the Koran it is necessary to distinguish the historical from the theological attitude. Here we are only concerned with those truths that are yielded by a process of rational enquiry, by scientific examination. Critical investigation of the text of the Quran is a study which is still in its infancy, By 1990, more than fifty years after Jefferys lament, we still have the scandalous situation described by Andrew Rippin:

I have often encountered individuals who come to the study of Islam with a background in the historical study of the Hebrew Bible or early Christianity, and who express surprise at the lack of critical thought that appears in introductory textbooks on Islam. The notion that Islam was born in the clear light of history still seems to be assumed by a great many writers of such texts. While the need to reconcile varying historical traditions is generally recognized, usually this seems to pose no greater problem to the authors than having to determine what makes sense in a given situation. To students acquainted with approaches such as source criticism, oral formulaic compositions, literary analysis and structuralism, all quite commonly employed in the study of Judaism and Christianity, such naive historical study seems to suggest that Islam is being approached with less than academic candor.

The questions any critical investigation of the Koran hopes to answer are:

1. How did the Koran come to us?That is the compilation and the transmission of the Koran.

2. When was it written, and who wrote it?

3. What are the sources of the Koran? Where were the stories, legends, and principles that abound in the Koran acquired?

4. What is the Koran? Since there never was a textus receptus ne varietur of the Koran, we need to decide its authenticity.

I shall begin with the traditional account that is more or less accepted by most Western scholars, and then move on to the views of a small but very formidable, influential, and growing group of scholars inspired by the work of John Wansbrough.

According to the traditional account the Koran was revealed to Muhammad, usually by an angel, gradually over a period of years until his death in 632 C.F. It is not clear how much of the Koran had been written down by the time of Muhammads death, but it seems probable that there was no single manuscript in which the Prophet himself had collected all the revelations. Nonetheless, there are traditions which describe how the Prophet dictated this or that portion of the Koran to his secretaries.

THE COLLECTION UNDER ABU BAKR

Henceforth the traditional account becomes more and more confused; in fact there is no one tradition but several incompatible ones. According to one tradition, during Abu Bakrs brief caliphate (632-634), Umar, who himself was to succeed to the caliphate in 634, became worried at the fact that so many Muslims who had known the Koran by heart were killed during the Battle of Yamama, in Central Arabia. There was a real danger that parts of the Koran would be irretrievably lost unless a collection of the Koran was made before more of those who knew this or that part of the Koran by heart were killed. Abu Bakr eventually gave his consent to such a project, and asked Zaid ibn Thabit, the former secretary of the Prophet, to undertake this daunting task. So Zaid proceeded to collect the Koran from pieces of papyrus, flat stones, palm leaves, shoulder blades and ribs of animals, pieces of leather and wooden boards, as well as from the hearts of men. Zaid then copied out what he had collected on sheets or leaves (Arabic, suhuf ). Once complete, the Koran was handed over to Abu Bakr, and on his death passed to Umar, and upon his death passed to Umars daughter, Hafsa.

There are however different versions of this tradition; in some it is suggested that it was Abu Bakr who first had the idea to make the collection ; in other versions the credit is given to Ali, the fourth caliph and the founder of the Shias; other versions still completely exclude Abu Bakr. Then, it is argued that such a difficult task could not have been accomplished in just two years. Again, it is unlikely that those who died in the Battle of Yamama, being new converts, knew any of the Koran by heart. But what is considered the most telling point against this tradition of the first collection of the Koran under Abu Bakr is that once the collection was made it was not treated as an official codex, but almost as the private property of Hafsa. In other words, we find that no authority is attributed to Abu Bakrs Koran. It has been suggested that the entire story was invented to take the credit of having made the first official collection of the Koran away from Uthman, the third caliph, who was greatly disliked. Others have suggested that it was invented to take the collection of the Quran back as near as possible to Muhammads death.

THE COLLECTION UNDER UTHMAN

According to tradition, the next step was taken under Uthman (644656). One of Uthmans generals asked the caliph to make such a collection because serious disputes had broken out among his troops from different provinces in regard to the correct readings of the Koran. Uthman chose Zaid ibn Thabit to prepare the official text. Zaid, with the help of three members of noble Meccan families, carefully revised the Koran comparing his version with the leaves in the possession of Hafsa, Umars daughter; and as instructed, in case of difficulty as to the reading, Zaid followed the dialect of the Quraish, the Prophets tribe. The copies of the new version, which must have been completed between 650 and Uthmans death in 656, were sent to Kufa, Basra, Damascus, and perhaps Mecca, and one was, of course, kept in Medina. All other versions were ordered to be destroyed.