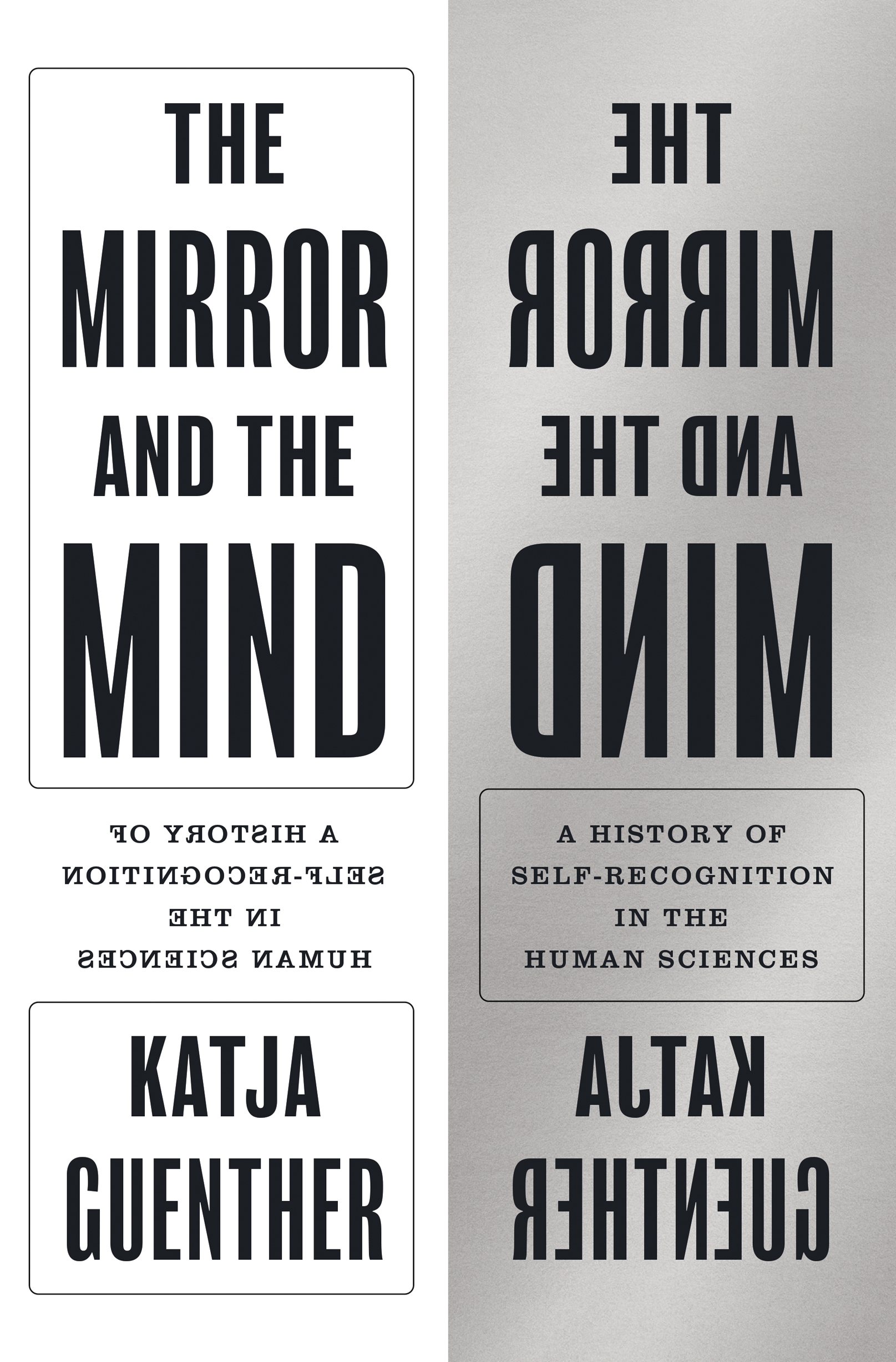

THE MIRROR AND THE MIND

PRINCETON MODERN KNOWLEDGE

Michael D. Gordin, Princeton University, Series Editor

For a list of titles in the series, go to https://press.princeton.edu/series/princeton-modern-knowledge.

The Mirror and the Mind

A HISTORY OF SELF-RECOGNITION IN THE HUMAN SCIENCES

KATJA GUENTHER

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2022 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

99 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6JX

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-23725-1

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-23726-8

Version 1.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022940842

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Eric Crahan and Barbara Shi

Production Editorial: Karen Carter

Jacket/Cover Design: Karl Spurzem

Production: Danielle Amatucci

Publicity: Kate Farquhar-Thomson and Alyssa Sanford

Copyeditor: Kathleen Kageff

To my family

Strange, that there are dreams, that there are mirrors.

Strange that the ordinary, worn-out ways

of every day encompass the imagined

and endless universe woven by reflections.

JORGE LUIS BORGES, MIRRORS

CONTENTS

THE MIRROR AND THE MIND

Introduction

PERIPATETIC PRACTICES

THE MIRROR SELF-RECOGNITION TEST is, in its experimental setup at least, extremely simple. A mirror is placed in an open space, often attached to a wall or standing vertically on the floor. The subject, perhaps a small child or an animal, is put in front of it. These circumstances are reproduced daily in countless homes around the world. Nothing could be more common. And yet, if present at the right time, paying attention to the right subject, one might observe something extraordinary. The subject might start by acting surprised at the image. It might approach it cautiously, or perhaps even aggressively, because the image seems to be similarly suspicious and unfriendly. But often, and after a little time, things begin to change. The subject no longer appears on edge. It is relaxed, happy even; perhaps it smiles. Playfulness has replaced suspicion. The subject might move its hands, its eyes shifting back and forth between the physical body and its reflection. It might open its mouth wide, leaning into the mirror so that it can see its teeth in the reflection, perhaps even pick out a piece of food caught between two teeth. Throughout this process, we are confronted only with outward behavior, the way the body moves at different stages of the encounter. But it is easy, unavoidable perhaps, to see these as the outward signs of an internal psychological drama, whereby the subject looks in the mirror and slowly comes to see itself. Might we be witness to the dawning of self-consciousness?

When I told people that I was working on a book about mirrors, I received a wide range of responses. A medievalist colleague cited Saint Paul: Videmus nunc per speculum et in aenigmate (1 Cor. 13:12, Vulg.) (We do not now see [God] but through a mirror, darkly). Another confessed to me that he used to stare at the mirror as a young man to see if he really existed (he did not say what was the result). One shared how intrigued she was with the use of mirrors in the film The Black Swan, where the mirror revealed to the protagonist Nina Sayers (played by Natalie Portman) her hidden and dark identities. Yet others evoked the myth of Narcissus losing himself in his reflected image, or Aesops dog, who foolishly jumped at his reflected image in a river to steal another dogs bone, thus losing the one he had to start with. My own motivation for the book came from a personal experience of observing my twin girls playing with a mirror when they were small. Despite its mundane ubiquity, the mirror remains a strange and endlessly fascinating object, because it seems to tell us new truths about who we are.

A History of Mirrors

The mirror has not always been an everyday item. In the ancient world, when mirrors were made from polished bronze or metal alloys, they were available only to a select few.

A dramatic increase in size and decrease in cost was secured in the sixteenth century by glassmakers from the island of Murano near Venice. Drawing on centuries of glassmaking expertise (and using the highest-quality ingredients including seawater, and a type of wood that burned to produce a clear flame), they were able to make glass that was pure and clear. Thanks to their refined technique, they were also able to make larger mirrors, measuring up to forty square inches. These brought the Republic of Venice substantial wealth, and its wares were prized across Europe and the Middle East.

The French broke the Venetian monopoly in the late sixteenth century. The company Saint-Gobain, heavily subsidized by the state, managed to lure a few artisans from Murano to Paris, where they perfected the method of casting large glass mirrors. It pervades the most intimate as much as the most public spaces. It has also, in the guise of the mirror test, pervaded the history of the modern mind sciences.

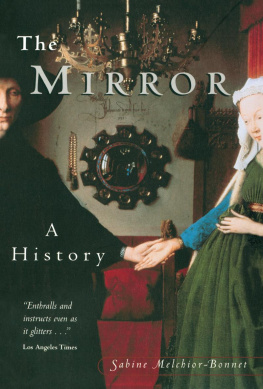

FIGURE 0.1. Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434. The mirror also has a revealing function: two people are entering the room, one of whom could be the painter. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Psychology and Its Others

The history of the mind sciences has traditionally been told as a sequence of different intellectual movements.

This book, by examining a single test, and following it wherever it appears, carves a less familiar path. The mirror test is particularly valuable because it allows us to think through the disciplinary richness of the mind sciences. For reasons that will become clear, the test often sat on the margins of different academic fields, connecting psychology with neurology, but also with evolutionary biology, psychoanalysis, anthropology, linguistics, and cybernetics. It also moved between pure and applied research, and research and therapy. It did not respect national borders either. As we will see, an analysis of the mirror test requires us to move between Germany, France, Britain, North America, and beyond.

Though it can be followed as a guiding thread crossing national and disciplinary lines, the mirror test did not form an intellectual tradition, in the sense of a clearly articulated network of textual references. Some mirror researchers appealed to a slowly expanding canonDarwin and Preyer, and then Lacan, Amsterdam, and Gallupand in the first two chapters of the book I will analyze the type of intellectual inheritance and influence with which most historians will be familiar. The later chapters, however, tend to deal with scientists who were mostly unaware of these predecessors, and worked independently. Often the mirror emerged in their work serendipitously. When mirrors are common household objects, one might easily encounter a mirror response by chance or integrate it into a research project as an ad hoc measure.