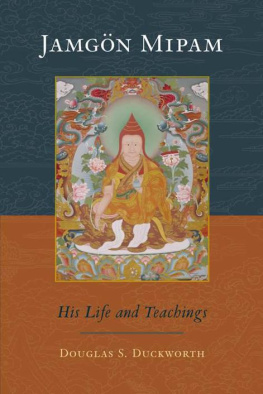

J AMGN M IPAM

His Life and Teachings

Douglas Duckworth

Shambhala

Boston & London

2011

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

2011 by Douglas Duckworth

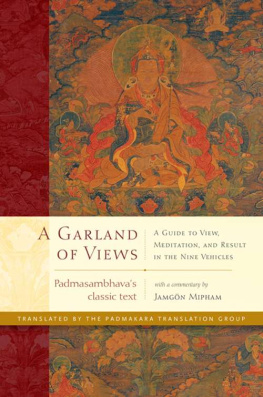

Cover art: Thangka of Jamgn Mipam by Noedup Rongae. Used with permission of Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Duckworth, Douglas S., 1971

Jamgn Mipam: his life and teachings / Douglas Duckworth.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes translations from Tibetan.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2763-9

ISBN 978-1-59030-669-7 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Mi-pham-rgya-mtsho, Jam-mgon Ju, 18461912. 2. Buddhist philosophy.

I. Mi-pham-rgya-mtsho, Jam-mgon Ju, 18461912. Selections. English. 2011. II. Title.

BQ972.I637D83 2011

294.3923092dc22

2011012950

C ONTENTS

This book contains many Sanskrit diacritics and special characters. If you encounter difficulty displaying these characters, please set your e-reader device to publisher defaults (if available) or to an alternate font.

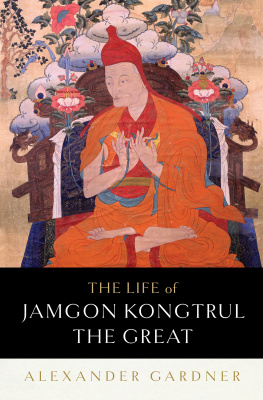

T HIS BOOK REVOLVES around one of the most extraordinary figures in the history of Tibet, Jamgn Mipam (18461912). Mipam (commonly written as Mipham but pronounced Mipam) shaped the trajectory of the Nyingma school, a Buddhist tradition from Tibet that traces its history back to its early transmission from India in the eighth century. Mipam is a major figure in this tradition, and in terms of the breadth and depth of his writings, he is in a class of his own. His works live today as part of the curriculum of study at several contemporary monastic colleges in Tibet, India, and Nepal. Thus, Mipam is not simply a towering figure of historical importance; he continues to hold a central place in a flourishing Buddhist tradition. Although he lived quite late in the long history of Buddhist development in Tibet, his influence on the Nyingma school has been enormous.

This book is an introduction to Mipams life and works. It is organized into three main sections: the first provides some general background; the second presents an overview of some of the main themes in his work; and the last offers translated excerpts from his writings. Using this framework, I hope to give a sense of who Mipam was and present a survey of the rich heritage he has passed on.

Part One gives a context for understanding Mipam and his writings. Not a lot of biographical information about Mipam is availablewhich is surprising, considering the contribution he made to Buddhist thought and monastic educationbut what we do know about his life and particularly from his works reveals that he was an extraordinary genius. He spent most of his life in meditation retreat, yet he was also actively involved in Buddhist scholarship. Mipam wrote extensively and not just on a few areas of Buddhist thought. He wrote on an incredibly wide range of scriptures and traditions, and his works address topics that extend well beyond the classic Buddhist scriptures. In addition to surveying these topics, Part One touches on some important features of Buddhist traditions in India and Tibet, providing a background for the tapestry of Mipams texts and allowing us to better appreciate his contribution.

Part Two gives an overview of Mipams interpretation of Buddhism. This section looks at major themes in his corpus to discover how he presents Buddhist theory and practice. In particular, this section looks more deeply into Mipams interpretation of emptiness, a central issue in Buddhist philosophy, and contrasts his interpretation with those of other prominent Tibetan figures.

Part Three contains a sample of his writings. Each of the excerpts includes a short introduction to provide a context and help the reader appreciate significant elements of the passage. The selections draw from a wide range of Mipams writings to illustrate the eloquent way in which he articulated the key issues explained in Parts One and Two. References to a number of these translations are provided in several chapters in Part Two, so the reader can immediately jump to the relevant selections to further explore the issues raised in the text.

Mipam was a sophisticated thinker who, in a grand synthesis, took on a number of difficult points in Buddhist thought. While this is an introductory book aimed at a general audience, it also deals with some tough issues in Buddhist philosophy, which is inevitable when dealing with someone like Mipam. For this reason, a person new to Buddhist philosophy may want to read slowly and even read some sections more than once. Taking time to assimilate ideas is crucial to the process of integrating the significance of philosophical texts, Buddhist or otherwise. Understanding Mipams works is certainly not easy, but to glimpse even part of the beauty of such a masters compositions is well worth the effort. Given that he spent so much of his life in meditation retreat, his philosophical writings are deeply rooted in an experiential orientation and can be read as quintessential instructions for Buddhist practice.

PART ONE

ONE

M IPAM WAS A descendent of the Ju ( ju ) clan. Clans and family lines are an important part of Tibetan identity, and they occupy a central place in Tibetan culture. Mipams father, who was a doctor, belonged to this clan, which is said to have a divine ancestry. The Ju clan gets its name from the word ju, which is interpreted to mean holding on to the rope of the luminous deities who descended from the sky. His mother was also of high status; she was a daughter of a minister in the kingdom of Deg, where Mipam was born. His homeland was a region at the center of intellectual culture in eastern Tibet in the nineteenth century.

His name, Mipam Gyatso, (which literally means undefeatable ocean), was given to him by his uncle. As is the case in the life stories of most prominent lamas in Tibet, Mipam is presented in his as a child prodigy. Yet given the momentous influence of such a recent figure as Mipam, we are left with relatively few details of his life.

His studies began when he was about six years old, and he memorized Ascertaining the Three Vows, an important Nyingma text on Buddhist vows. of moral disciplinethe foundation of all Buddhist practices. Further, this text covers a wide range of Buddhist teachingsfrom the Lesser Vehicle all the way to Secret Mantraand shows how they all can be integrated without contradiction, which is a major theme throughout Mipams works.

When he was only ten, Mipam was said to be unobstructed in reading and writing, and he began to compose a few short texts. Some traditional Tibetan scholars claim that among his earliest compositions, at the age of seven, no less, was his famed Beacon of Certainty, a masterwork of philosophical poetry. This would be an amazing feat and is a testament to the high regard in which Mipams scholarship and intellect is held.

Mipams creative intellect was not restricted to mainstream Buddhist topics. While Gendn Chpel (19031951)the famous Tibetan author, rebel, and iconoclastis known for his commentary on the Kma Sutra (the famed sex manual of ancient India), Mipam was actually the first Tibetan to write a commentary on it. This shows both his originality and the eclectic character of his literary works.

According to his biography, he became a novice monk when he was twelve, following the local tradition of his homeland. He entered the monastery of Jumohor, which is a branch of the Nyingma monastery of Zhechen. There he came to be known as the little scholar-monk. Early in his life, when he was about fifteen or sixteen, he did a retreat on Majur in a hermitage at Junyung for a year and a half. Majur is a deity associated with wisdom, and throughout his life, Mipam had a special connection with this deity. Through successfully accomplishing this practice in his youth, it was said that he knew the Buddhist scriptures, as well as the arts, without studying. From then on, he did not need to study texts other than simply receiving a reading transmission ( lung ). A reading transmission involves the formal authorization to study a text when a teacher imparts the blessings of the embodied meaning of the words by reading it aloud to a student. Oral transmission from teacher to student is an important part of the Buddhist tradition in Tibet.

Next page