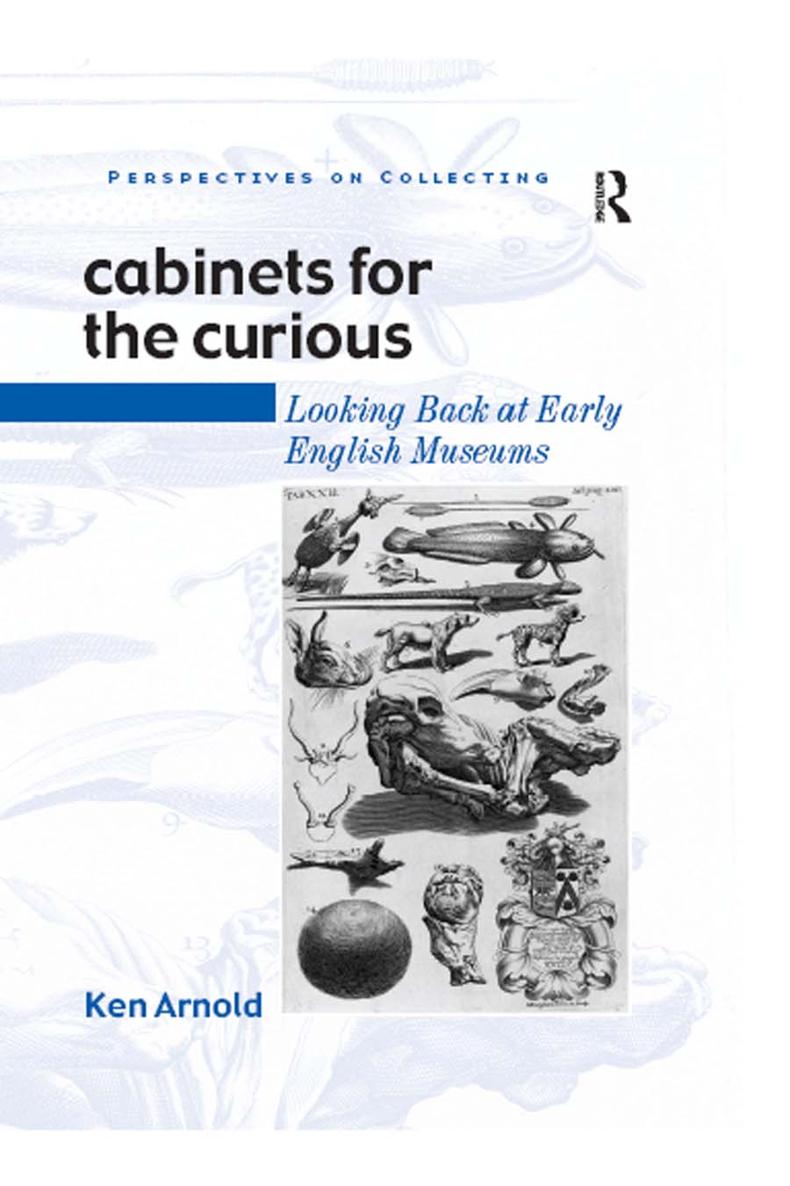

CABINETS FOR THE CURIOUS

For Raymond Arnold (19232004)

who first showed me how

the past could live in the present

Cabinets for the Curious

Looking Back at Early English Museums

KEN ARNOLD

The Wellcome Trust, UK

First published 2006 by Ashgate Publishing

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Ken Arnold 2006

Ken Arnold has asserted his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Arnold, Ken, 1960

Cabinets for the curious : looking back at early English museums. (Perspectives on collecting)

1. Museums England History 17th century 2. Museum techniques England History 17th century

I. Title

069'.0942'09032

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Arnold, Ken.

Cabinets for the curious: looking back at early English museums/Ken Arnold.

p. cm.(Perspectives on collecting)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-7546-0506-X (alk. paper)

1. MuseumsEnglandHistory. 2. MuseumsEnglandPhilosophy. 3. Cabinets of curiositiesEnglandHistory. 4. Collectors and collectingEnglandHistory. 5. Museum techniquesEnglandHistory. I. Title. II. Series.

AM42.E54.A76 2005

069'.0942dc22

2004020631

ISBN 13: 978-0-7546-0506-5 (hbk)

Contents

The study of collecting is a crucial facet in the contemporary turn towards the understanding of social practice, seen as the medium through which individuals and communities create self-identity. Social construction of the meanings of material culture is at the heart of this project, and the collecting process, through which objects are put into meaningful relationships seen as producing knowledge, value, aesthetic and prestige, is central to it. Perspectives on Collecting is intended to bring together detailed studies and broader over-views, drawn from the analysis of a wide range of collecting practices, which together will develop a sustained exploration of the field.

Susan Pearce, General Editor

A number of recent volumes have shed much light on the collecting habits upon which Renaissance cabinets of curiosities were based. This is an examination of their English counterparts, but in it I am less concerned with how Englands first museums were actually amassed. Another body of contemporary work has added considerably to our understanding of people and institutions that collect today. My focus on contemporary practice is slightly different too. For as an exhibition maker by trade, my interest is almost invariably in attempting to animate objects after they have been accessioned. And similarly, my historical focus is on what people did with objects after collections had been assembled. This then is a book about how to use museum objects then and now.

The initial ideas for this work were formed during research I undertook for a Ph.D. completed for Princeton University in 1992. Almost all of my professional life since then has been spent in museums and with collections. The structure and argument of the book deliberately juxtaposes historical and contemporary material in the same fashion that I have attempted to make the most of the parallels between academic and vocational pursuits.

As a contribution to the history of science the historical essays that follow seek to highlight the role played by museum makers and keepers in the production of factual knowledge during the scientific revolution. A small contribution to our understanding of how early modern science developed in England, this history also spotlights a foundational moment in the history of museums. For no matter how great the subsequent changes in their management, use and conception have been, the idea that museums could provide isolated spaces in which objects could be kept and contemplated has remained at the heart of their mission ever since. It is my contention that approaches taken to this challenge in seventeenth-century England can usefully illuminate contemporary work.

This book therefore serves two complementary functions. First, it provides a detailed cultural history of early-modern English museums within the context of seventeenth-century science. Second, it uses that story to establish an intellectual framework in which to make new sense of questions that trouble museums today about both the role of objects within them as well as their broader social function.

Historians of idea have maybe especially good reasons to be aware of the pyramid of support that keeps afloat any intellectual enterprise. Working, as I have, for more than ten years on this project has extended the base of this particular pyramid far and wide, so compounding the sense that I cannot possibly mention all those to whom thanks are due.

In my early efforts to tackle the historical material for this book I gained much from the example of teachers gathered at Princeton University in the late 80s and early 90s. Even more significant was the extremely lively and enjoyable companionship of other post-graduate historians. Amongst them one deserves particular thanks. Evidence of John Carsons ability to comment with supportive insight and sympathy, and then to make it clear that more was possible more profound questions, more rigorous arguments, more convincing evidence, more daring connections and more elegant rhetoric is to be found on just about any page in this volume.

It was towards the end of my Ph.D. research that I gained my first exposure to the awe-inspiring challenge of making a public exhibition. This was at the Smithsonian Institution, and since then I have been privileged to undertake similar work at the British Museum, the Livesey Museum, Croydon Clocktower, the Science Museum and Wellcome Trust, all in London. During this time, I have lost track of the number of occasions when I have written or spoken about the collaborative nature of exhibition work. Fellow curators, designers, marketing and communications professionals, artists and scientists, lawyers and librarians, and even an occasional conservation scientist, have all influenced my understanding of what museums do.

A few other individuals need special mention. In Croydon I was fortunate enough to work with the inspirational museum figure Sally MacDonald, and from there to be hired by another, Janet Vitmayer, at the Livesey Museum. In a range of projects at the British Museum I have been lucky to encounter a number of influential figures, particularly John Mack. In 1999 I was very fortunate in joining an interdisciplinary research group centred in Irvine, California, headed up by Bruce Robertson and Mark Meadow. In master-minding an audacious research project under the suggestive title of Microcosms, they spurred me on to a very fruitful development of my ideas. My understanding of contemporary museums was also significantly enriched by a period of study at Leicester University, where I was taught by Gaynor Kavanagh, Eileen Hooper-Greenhill and the wise-woman of museum studies Sue Pearce. Her specific interest in and encouragement of my work have much influenced this publication. In ten years of exciting employment at the Wellcome Trust, I have gained much from many colleagues.