ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS: FOLK MUSIC

Volume 7

VILLAGE SONG & CULTURE

VILLAGE SONG & CULTURE

A Study Based on the Blunt Collection of Song from Adderbury North Oxfordshire

MICHAEL PICKERING

First published in 1982 by Croom Helm Ltd

This edition first published in 2016

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1982 Michael Pickering

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-138-94398-8 (Set)

ISBN: 978-1-315-66734-8 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-95410-6 (Volume 7) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-65075-3 (Volume 7) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

Village Song & Culture

A STUDY BASED ON THE BLUNT COLLECTION OF SONG FROM ADDERBURY NORTH OXFORDSHIRE

MICHAEL PICKERING

1982 Michael Pickering

Croom Helm Ltd, 2-10 St Johns Road, London SW11

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Pickering, Michael

Village song and culture.

1. Folk-songs, English - England - Adderbury - Social aspects

I. Title

301.57 ML3652

ISBN 0-7099-0059-7

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Biddles Ltd, Guildford and Kings Lynn

CONTENTS

FOR MY PARENTS

First and foremost, I wish to thank those people in or around Adderbury who have provided the oral information which proved so vital in developing an understanding of the village society of their childhood and of their Victorian forebears. Their names are in the text, but I am particularly in debt to Mr. Harry Tamp Austin, the late Fanny Hitchman, the late Wilf Walton, and Mrs. Winnie Wyatt.

I have written this book in the spaces between other tasks of work, but it derives essentially from research conducted at the Institute of Dialect and Folk Life Studies at Leeds University, and funded by the Department of Education and Science. For help and conversation in those years, my thanks to Stewart Sanderson and Steve Caunce. In my attempt to refer song to social context and to village culture generally, and to interpret song in relation to that context and culture, I have been helped most of all by Tony Green. His friendship and counsel display a great generosity. Several other friends and colleagues offered comments and encouragement, and I am grateful to Dan Schiller, Barry Troyna, Iain Steele, Mike Scott and Kevin Robins. David Buchan read through an earlier version, and provided useful criticism. I am indebted as well to Jeremy Hawthorn, who took time out from other commitments and kindly read through the manuscript. Any surviving errors and ineptitudes rest on my head alone.

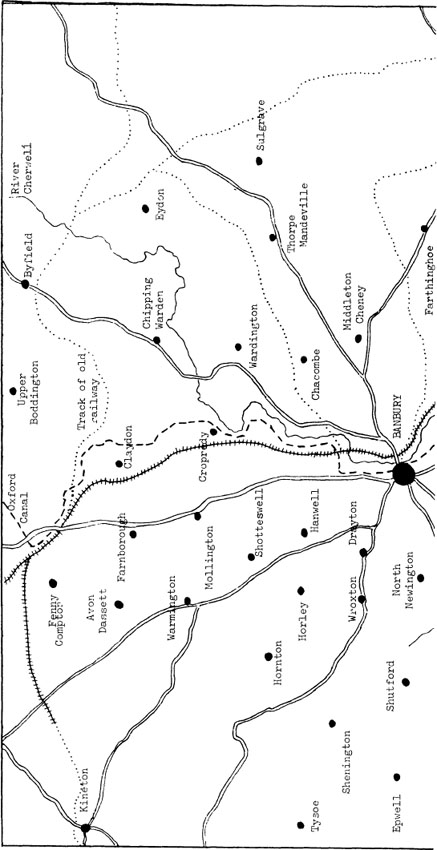

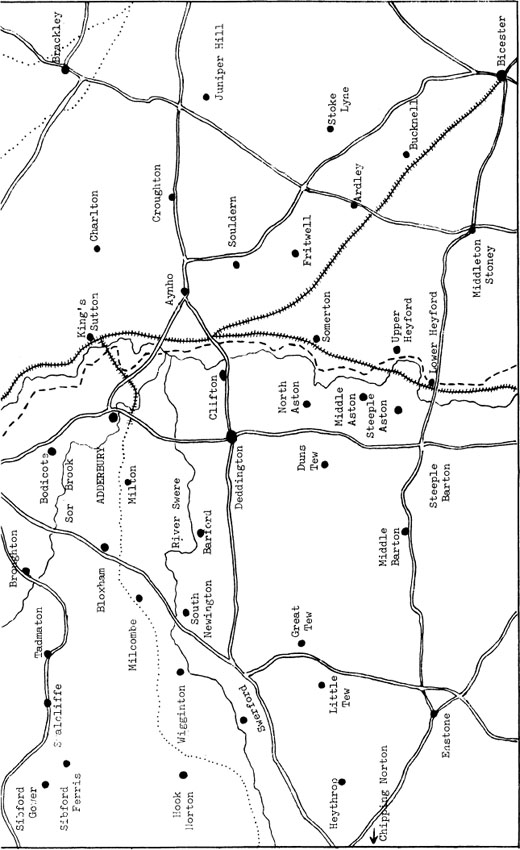

Alison Troyna drew the sketch map of Banburyshire, and Penny Harlow patiently and efficiently typed up the final script. Many other people, too numerous to mention by name, have also given more casual help and co-operation. To all of them I extend a sincere gratitude. Lastly, and by no means least, my friend Isabel has provided invaluable assistance and support in the haul towards completion of the text, and to her I owe my greatest debt.

Sketch Map of Banbury and Outlying District

The songs on which this study is based were once vibrant in the throats and ears and minds of living people. I have attempted to explore their roles and meanings in relation to the lives of those people, and to the cultural tradition and practice of which they were an integral part. In 1907, Cecil Sharp remarked on how intimately folk-singing and folk-dancing have, in the past, been bound up with the social life of the village, () and yet reading the many collections published since the early twentieth century upsurge of interest in what was ideologically conceived as the traditional song of country folk, precious little insight into the integration of rural life and song is to be gleaned.

The art of village song, though interwoven with particular traditions and the sense of the past inherent in those traditions, cannot be divorced from the historically specific existence and consciousness of working men and women. It must be released from the sanctified amnesia of a folk culture, and located within the particular patterns of social and material experience, solidarity and conflict, exploitation and resistance, to which village culture as a whole gave expressive shape and meaning, however obliquely or obscurely. The actual ways in which songs related to, and were a part of village life, are of course highly problematic, but it is an understanding of the place of song in the social life of villagers which this study endeavours, most of all, to reach. It is my contention that without an attempt to establish the nature of the relationship of song to social context, what is said to constitute an essential part of our national cultural heritage remains of no more value than the paper on which it is printed. No amount of pretty lettering or bucolic woodcuts will alter that. Furthermore, the mere printing of songs without reference to the contexts in which they were performed is an activity as laudable and valuable, historically, as the collection and display of Victorian pince-nez or Edwardian monocles.

A basic premise of this study is that there is no existence of the text, in the song and singing tradition on ) This incorporation cannot satisfactorily be explained by a catch-all notion of false consciousness. Whether village custom and culture was contestatory or incorporated cannot be decided at an abstract level; such questions must be addressed in relation to complex and shifting patterns of cultural domination, power and struggle, and these can only be seen in definite and specific historical terms. The achievements of the English folk song and dance movement must be set within the context of the cultural expropriation and the historical decontextualisation of these texts, and it is the negative and disabling effects of this side of those achievements that I am concerned here to counteract by means of reconstituting these texts in their original milieu, and in relation to the social practices which produced and informed them. I seek to gain them back, in other words, for the people from whose culture they were extracted, to be placed as unproblematic remnants of a past and more harmonious way of life in the national gallery of literature.

![Othmar Keel - The Song of Songs [Song of Solomon]](/uploads/posts/book/82605/thumbs/othmar-keel-the-song-of-songs-song-of-solomon.jpg)