First published in 2018 by

First published in 2018 by

Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC

With offices at:

65 Parker Street, Suite 7

Newburyport, MA 01950

www.redwheelweiser.com Copyright 2002, 2018 by Ceisiwr Serith

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC. Reviewers may quote brief passages. Original edition published in 2002 by Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC.

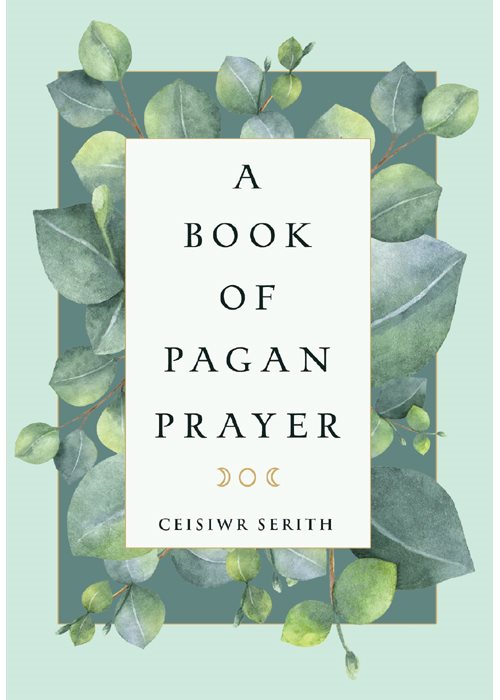

ISBN 978-1-57863-255-8. ISBN: 978-1-57863-649-5 Names: Serith, Ceisiwr, 1957- author. Title: A book of pagan prayer / Ceisiwr Serith.

Description: Newburyport : Weiser Books, 2018. | Originally published: 2002.

| Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018035607 | ISBN 9781578636495 (5 x 7 pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Prayers. | Neopaganism--Prayers and devotions. | Neopaganism--Prayers and devotions.

Classification: LCC BF1572.P73 S47 2018 | DDC 299/.94--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018035607 Cover design by Kathryn Sky-Peck

Interior black sun graphic by Ratatosk, dist. under CCA-Share Alike 2.0

Interior by Steve Amarillo / Urban Design LLC

Typeset in Ascender Tinos and Emigre Mrs. Eaves Printed in Canada

MAR

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter For Phyllis R. Huggett

who told me I was smart

CONTENTS

PREFACE FOR THE NEW EDITION

When I started writing this book back in the 1980s, I was concerned with how not only it, but also the very concept of Pagan prayer, would be received. I had often read and heard comments like, Pagans exercise their own power through magic; they don't grovel before the gods in prayer. This hostility towards prayer disturbed and confused me.

Though I read books on neo-Paganism, I also read books by and about ancient Paganism even more, and one thing I encountered over and over was prayer. All of the Indian Vedas were prayers. Characters in Greek tragedies prayed at the drop of a corpse. Cato provided texts of Roman prayers. And this was just in the Indo-European cultures. Spreading my net wider, I found prayers in the Americas, Africa, the South Pacific, China, Japaneverywhere people held to religions.

And not only in the Abrahamic religions, as seem to be believed by many neo-Pagans. This universality can only be explained, I believe, by an equally universal desire to make contact with the divine, whether seen as personal or not. This desire is found deep within every human being, and comes to the fore in those who are religious. I needn't have worried. My book fell on fertile ground. Since then, many more Pagans have involved themselves in prayer and in the writing of prayers.

While I would like to think that my books played a part in this, I believe that there are other, more powerful factors at work. First, there is the universal desire to pray. I believe that many Pagans had a hunger that eventually burst forth in the practice of prayer. Second, I saw the development of a form of Wicca and neo-Paganism that emphasized deities beside the God and the Goddess. This awoke a desire for a personal relationship with them and a need to differentiate between them. It also raised the question of why one would worship different deities; the obvious answer was that they fulfilled different concerns, which led to the need for prayers to address those concerns.

Third, the development of the worship of more than two deities led to more research into the ancient information. This was further inspired by the rise of Reconstructionist Paganism, of people who wanted to worship in ancient ways; their research discovered the importance of praying in Paganism. Fourth, the mainstreaming of Paganism has decreased the need for Pagans to define themselves by what they aren't. This has meant a lessening of wholesale rejection of the practices of other religions. These factors and no doubt other ones I haven't identified have led to a rebirth of Pagan prayer. Websites, social media, and Pagan magazines now frequently feature prayers, both ancient and modern, and now, given permission to pray, Pagans have responded. I am obviously happy with this.

I believe that it will lead to a deepening not only of our relationships with the sacred beings, but also of our awareness of the sacred in the world we live in. A person who immerses themselves in prayer is immersing themselves in the sacred. This can only be to our benefit. In writing this and other books, I've learned a lot about prayers. Since this learning hasn't caused me to reject major parts of what is in this book, I haven't made any radical changes to it. I would like to talk a little bit about the changes I have made and a little bit about what I've learned about prayer since the book's first publication.

In it, I emphasize the function of prayer as communication. Communication has to be between. There is a speaker, and there is a listener or listeners. In prayer, these listeners are the deities, the ancestors, the nature spiritsany or all sacred beings. But if you look at my prayers, you'll find ones that don't seem to have a sacred audience. These are divided into two types.

The first is to things that don't seem to be numinousa bowl of water, for example. However, anything can be seen as sacred in some way or to some extent. This is like the Shinto idea of a kami; a numinous presence that is possessed by anything special. Not just the sun, not just a mountain like Mt. Fuji, but even a well-made knife or teacup can have (or be, the distinction is not necessary) a kami. This connection may be immediately perceived.

But it may be created, especially in the West, by acting as if the kami existed, by talking oneself into belief in its existence. In this way, the entire universe can be made sacred, which is something that many Pagans believe already. The second exception is one where there seems to be no recipient at all. These prayers come across as simple poems that express a situation. But even here there is a recipient. The situation itself is sacred and may be seen as receiving the prayer.

Or the recipients may be all those who hear the prayer, even if it is only a single person. And it is not the ordinary people, but the part of them that is identified as sacred. By treating the person as sacred, they are raised to a status of a numinous being who may appropriately receive prayer. The most obvious changes that readers of the first edition will notice is that I've rearranged the chapters, rearranged the prayers in the chapters, moved some prayers to different chapters, and created two new chapters from one. I think this makes the book easier to use. The chapters are now arranged similarly to my second book A Pagan Ritual Prayer Book; that is, in an order that follows that of a ritual.

I moved all the litanies to appropriate chapters, assuming that most people can figure out what prayers can be used. I discovered that some prayers were in the wrong chapters, and fixed that. I realized as I was doing this that the prayers weren't labeled as to the deities they were addressed to and that they weren't in any logical order within each chapter. They are now in the order of General, the God and Goddess, the God, the Goddess, the All-Gods, other deities (alphabetically), the Ancestors, and the Land Spirits. You will also find that I've added a few deities. I also had the happy opportunity to fix a major problem with the first version.

Next page

First published in 2018 by

First published in 2018 by