FOREWORD

Pam Grossman

I confess I was a bit wary when Frances reached out to request I sit for a portrait for Major Arcana: Witches in America . As someone who has identified as a witch for most of her life, I was used to piquing peoples curiosity. Yet my experiences of being put on display to exemplify someone elses idea of what a witch is hadnt always gone well.

Frances, however, understands that the image of myself as a witch and the image of myself as a person are interlinked. No matter which of these aspects is being emphasized to the public, I want to be sure that Im represented as multi-dimensional and powerful on my own terms. After speaking with her at our initial meeting, I felt assured that Frances wasnt looking to frame me as a freak or a fetishized femme fatale. Her approach is to depict modern witches as wholly self-possessed individuals. She realizes that the expression of my magic and the depiction of my personhood needed to be as integrated in her photographs as they are in my own identity.

Both Frances and I believe that every photograph of a woman or female-presenting individual has the potential to chip away at the wall of sexism thats been constructed over centuries. As a photographer, Frances has built up a riveting body of work that centers the female experience without exploiting it or trivializing it. That she has now decided to focus her camera on witches is particularly significant, for in doing so she is excavating the history of female imagery construction at its very foundations.

It can be argued that the image of the witch is one of the earliest examples of widespread propaganda against women. Though beliefs and stories about witches have existed in virtually every culture throughout history, the hyper-sexed, homicidal, Satan-worshipping witch as we know her came to prominence in fifteenth-century Europe. Friars of various sects of the Catholic church traveled throughout western Europe to warn villagers that bewitching, bedeviled dames dwelled among them, but it was the advent of the printing press that caused these ideasand, crucially, imagesabout witches to proliferate and spread to the masses.

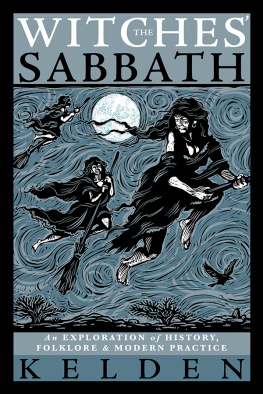

Heinrich Kramers Malleus Maleficarum (or The Hammer of Witches ) of 1486 stated that although anyone could be a witch, women were far more likely than men to fall prey to Satans persuasive tactics due to their innate gullibility, weakness, and insatiable carnality. Texts like this one not only informed people about the existence of nefarious witches, but many included visual renderings that showed them shape-shifting into animals, attacking unwitting neighbors with weather magic or weaponry, and happily swooning in the devils embrace. Their hair was often shown loose and uncovered, and they rode the skies with cooking forks, brooms, or other phallic stand-ins between their legs. Artists of the age such as Albrecht Drer and Hans Baldung Grien were inspired by these tomes and took things a step further by drawing witches that gathered in the nude to make all sorts of trouble. Their artworks were collected by wealthy men and kept in back rooms or curiosity cabinets for private titillation.

Over the next 200 years, witch-hunting manuals and pamphlets circulated throughout Europe and, eventually, the New England colonies. Tragically, this anti-witch crusade cost tens of thousands of people their lives over the next several centuries, and scholars estimate that between 7585 percent of those accused were women. Though its anachronistic to apply film critic Laura Mulveys male gaze terminology of the 1970s to sixteenth- and seventeenth-century witch hunting, its fair to point out that it was exclusively men who were authoring and illustrating the books that popularized the notion of depravedand usually femalewitches. And it was women who paid the price for it.

Since the nineteenth century, however, the word witch has taken on positive and often feminist connotations. Undoubtedly, Hollywood films such as MGMs The Wizard of Oz of 1939, the post-war British Pagan Revival, and the subsequent mid-twentieth-century birth of the modern religion of Wicca had a huge hand in its resignification. So, too, did the rise of women across societal strata. For who better to symbolize a subversive, feminine force than the marginalized, magical witch?

It is through this historical lenspardon the punthat Francess remarkable photographs are best viewed. Her pictures of modern witches offer a respectful, anthropological, and quite beautiful glimpse into a complex spiritual and political movement. But they also pull double duty in depicting these women and genderqueer individuals as subjects and not objects, thereby decoupling both feminine imagery and witch imagery from their centuries-old baggage of straight cis-male desire, fear, and control.

Some of these witches are sexy, but they are never objectified. Some might be shadowy, but they are never posed to shock. A photograph is, by nature, a flattened, two-dimensional picture forever frozen in time. And yet somehow, Francess series feels nuanced and fully formed, as does each witch within it. Individually, each subject comes across like their own craft-master and knowing guide who has graciously welcomed us into their sacred space.

This was certainly the intention. When Frances invited me to participate in this project, what she was really doing was inviting me to invite her. I was told I could wear whatever I felt most comfortable in and to choose a location that felt right to mewhich was, in my case, my home. When Frances arrived, she was curious, kind, and unimposing, while still deftly making use of natural light and artful angles. She managed to make my Brooklyn apartment feel suspended between worlds yet totally grounded. And she made me feel, well, enchanting and sincerely myself.

Taken as a whole, Francess pictures reveal a diverse and complex spectrum of contemporary witchery. Those who sat for her camera vary in practice and style, background and lived experience. Some of us are rather open about our witchcraft as we navigate our daily lives and shape our digital personas. For others, this was the first time they identified as a witch in public, but they trusted Frances as I did, for they too felt she would handle their image with care.

Together, these portraits form an eclectic visual coven that includes many different reflections of what it means to be a witch and how to truly represent female-led meaning-making. What those of us fortunate enough to be initiated into it share is a stance of strength, searching, and self-empowerment.

Witches might interface with invisible entities of whatever name we choose to call them. But in rendering us more visible, Frances has furthered our fight against patriarchal constraints and spiritual oppression. Shes cast a circle of change with the snap of a shutter.

And if thats not magic, I dont know what is.

Pam Grossman is the creator and host of The Witch Wave podcast and the author of Waking the Witch: Reflections on Women, Magic, and Power (Gallery Books) and What Is a Witch (Tin Can Forest Press). Her writing has appeared in such outlets as the New York Times , the Atlantic , TIME , Ms. Magazine , and her occulture blog, Phantasmaphile . She is cofounder of the Occult Humanities Conference at NYU and has been called the Terry Gross of witches ( New York Magazine ).

AUTHORS NOTE

Modern witchcraft comprises a vast landscape, home to many varying opinions and politics. These portraits and accompanying textual accounts represent the topography of that landscape. The opinions reflected herein are the subjects own.