Mark Durie is a theologian, human rights activist and pastor of an Anglican church. He has published many articles and books on the language and culture of the Acehnese, Christian-Muslim relations, and religious freedom. He is a graduate of the Australian National University (BA Hons, PhD) and the Australian College of Theology (DipTh, BTh Hons). After holding visiting appointments at the University of Leiden, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Stanford University, and the University of California at Los Angeles and Santa Cruz, he became Head of the Department of Linguistics and Language Studies at the University of Melbourne, was elected a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities in 1992, and awarded an Australian Bicentennial Medal in 2001 for contributions to research.

Copyright February 2010 by Mark Durie No part of this work may be reproduced by electronic or other means, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing from the author, except as provided by United States of America copyright law. Scripture taken from the Holy Bible,

New International Version.

Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984 Biblica.

Used by permission of Zondervan Bible Publishers. Mark Durie, 1958

Published by felibri.com for Deror Books.

Contents

Acknowledgements

This project would have been impossible to undertake without the path-breaking work of Bat Yeor, who for more than thirty years pioneered and established the study of dhimmitude. I first encountered Bat Yeors writings in the mid-1990s, and the influence of her careful scholarship, original ideas, and profound analyses, developed in articles and books from the 1970s on, can be found all throughout this book. She was the scholar who first demonstrated the causal link between Islamic legislation and theology on the one hand, and the psychosocial condition of dhimmis on the other, a link which transcends time, geography and ethnicity. She made available a wide variety of painstakingly gathered primary source materials on the dhimma and dhimmi peoples at a time when this subject was shrouded in silence and denial.

I also gratefully acknowledge my indebtedness to the compilation of sources in Andrew Bostoms two edited collections on jihad and Islamic antisemitism, and also to the Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought for the collection of commentaries made available through altafsir.com.

I am thankful for the support of so many individuals, whose feedback, advice and encouragement have contributed much to the genesis of this book. Without their help, this book could never have been written.

I particularly wish to thank Esther Abihail for her invaluable assistance in translating classical Arabic sources.

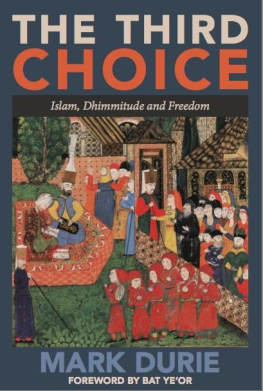

Front Cover: A depiction of the annual collection known as devshirme of Christian children. In a system of human tribute, boys were enslaved from the dhimmi communities of the Ottoman Empire, and either sold or converted to Islam and trained to serve as janissaries in the sultans army. A minority also became administrators.

In this scene, set somewhere in the Balkans, selected Christian boys, clothed in their new uniforms, stand ready for travel under the watchful eye of a guard, as functionaries count funds and write up lists of names. To one side, a mother and her priest remonstrate with a janissary officer, once a devshirme boy himself; at the back a distressed woman stands with arms wide as a girl clings to her dress; and at the lower right a father stands ready to hand over his son, as an older man looks on with compassion. (From the Sleymanname , a sixteenth century illustrated history of Sleyman the Magnificent, preserved in the Topkapi Palace Museum, Istanbul.)

Foreword by Bat Yeor

Since 9/11 the concept of dhimmitude first elaborated in the 1970s and initially known only to a handful of specialists has become widely recognized as its complexities and implications have been investigated and popularized. The first path breaking, iconoclastic presentations of dhimmitude as an aspect of history are being transformed into rich and diverse analyses of modern history and sociology. Mark Duries book belongs to this new trend, but has the added distinctive that it seeks the healing of those affected by dhimmitude.

Although conceived and written with a profound Christian sensitivity, Duries book can be read with the greatest profit by people from all persuasions, including atheists. In The Third Choice , the author examines the most crucial challenges of this new century. Today, whoever does not have a clear understanding of the complexities of the word dhimmitude can be considered an illiterate in matters of modern international policy, and blind to present and future realities.

Durie exposes in clear language the multidimensional aspects of dhimmitude, a concept that pertains to a fourteen-centuries-old civilization, birthed through jihad , and structured in accordance with the strict requirements of the Sharia . Dhimmitude has produced endless wars and suffering, and left its mark on countless historical and literary documents. Dhimmitude is the captive history of captive non-Muslim peoples, conquered by jihad and distributed across Africa, Asia and Europe. The author examines with rigorous precision the basic foundations of Islam the Quran, hadiths , sira and Sharia and exposes their inner connections with the political, economic and social system of dhimmitude for which they are the basis, and over which they exercise religious guardianship.

The strict scholarly rationalism of the author is particularly evident in the chapter on the theological significance of jizya , the head tax paid by non-Muslims under Islamic rule. Here Durie brings numerous and irrefutable sources illustrating the meaning, implications and religious justification of the jizya , which is the cost paid by non-Muslims for the right to live, albeit in humiliation. The jizya ritual, writes Durie, forces the dhimmi subject through his participation in it to forfeit his very head if he violates any of the terms of the dhimma covenant, which has spared his life. The author sheds new light on the jizya ritual, which he calls an enactment of ones own decapitation. His discussion of this virtual beheading brings new depth to the Muslim-non-Muslim relationship. Still today in the jihad wars throughout the world, or the jihadists threats against the West the jizya s symbolism expresses a fundamental dimension of the theological and political relationship between Muslims and non-Muslims.

Too few Westerners grasp that the concept of dhimmitude is crucial to understanding the relationship between Islam and non-Islam. As Durie argues, through a conspiracy of silence, the heads of state, church and community leaders, universities, and media smother its reality under a blanket of ignorance. With numerous examples, the author denounces this intimidated concealment, which, he affirms, is undermining Western Judeo-Christian civilization and is contrary to human freedom and dignity.

While the authors study encompasses a wide register of political and legal areas, he does not neglect the human impact of dhimmitude, with its painful manifestations of moral abjection, self-destruction, fear, denial and loss of dignity. Durie reminds us, with compassion and empathy, that scholarly studies on dhimmitude should not mask the physical and moral sufferings of populations living in perpetual denial of their most basic rights and personhood. The dimension of this human tragedy, perpetuated through generations, is a predominant concern of his mission, since he dedicates his book to the healing and freedom of all those who have fallen within the reach of dhimmitude, whatever their religious convictions, non-Muslim and Muslim alike. His purpose is to offer resources for understanding these subjects and the links between them. The ultimate purpose of the book, to which the chapters take the reader in stages, is to offer resources for securing freedom from the legacy of dhimmitude.