Contents

Guide

Page List

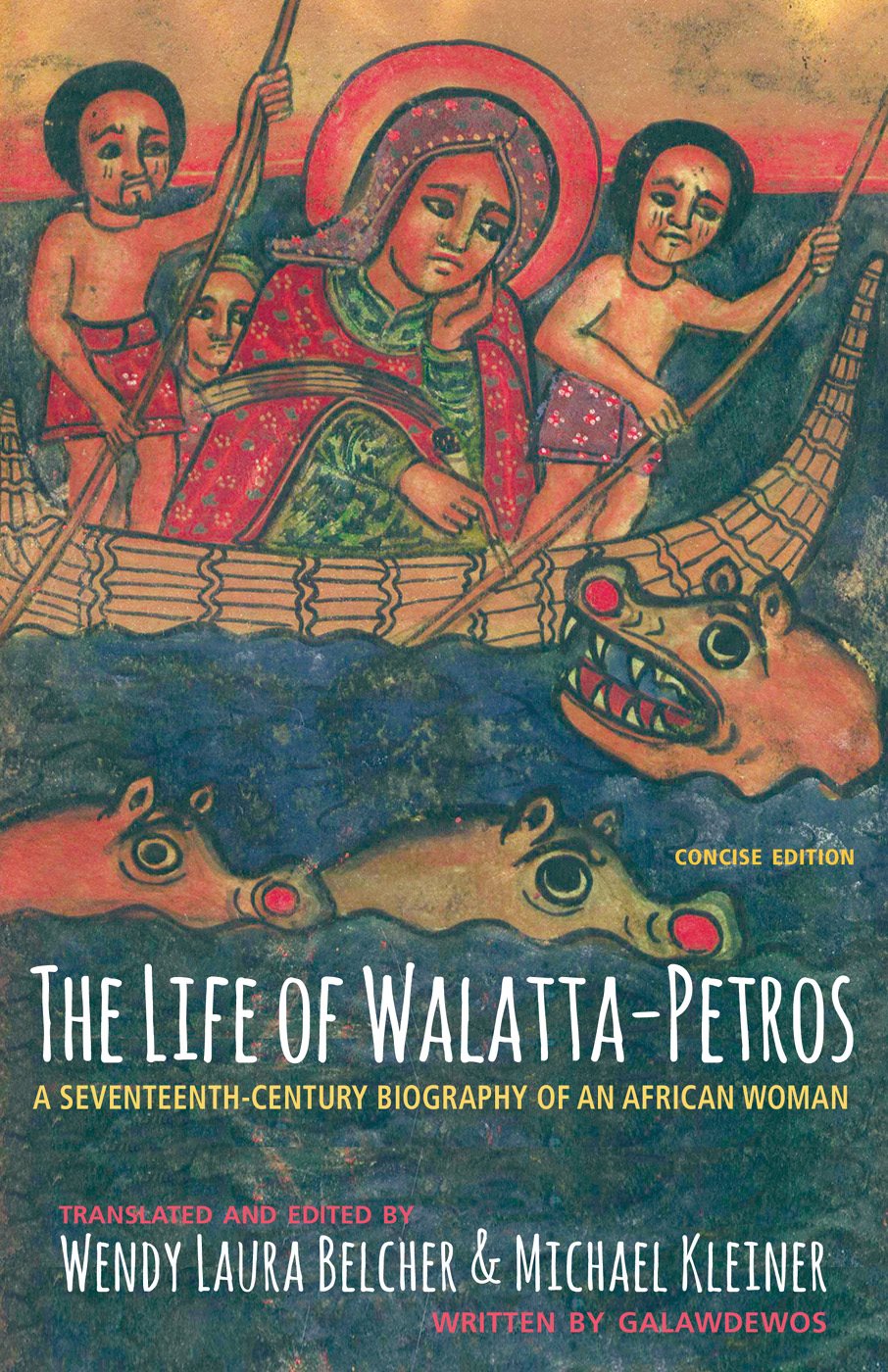

THE LIFE OF WALATTA-PETROS

THE LIFE OF WALATTA-PETROS

A SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY BIOGRAPHY

OF AN AFRICAN WOMAN

CONCISE EDITION

TRANSLATED AND EDITED BY

WENDY LAURA BELCHER AND MICHAEL KLEINER

WRITTEN BY GALAWDEWOS

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2018 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

This book includes material originally published in The Life

and Struggles of Our Mother Walatta Petros: A Seventeenth-Century

Biography of an Ethiopian Woman

(copyright 2015 by Princeton University Press).

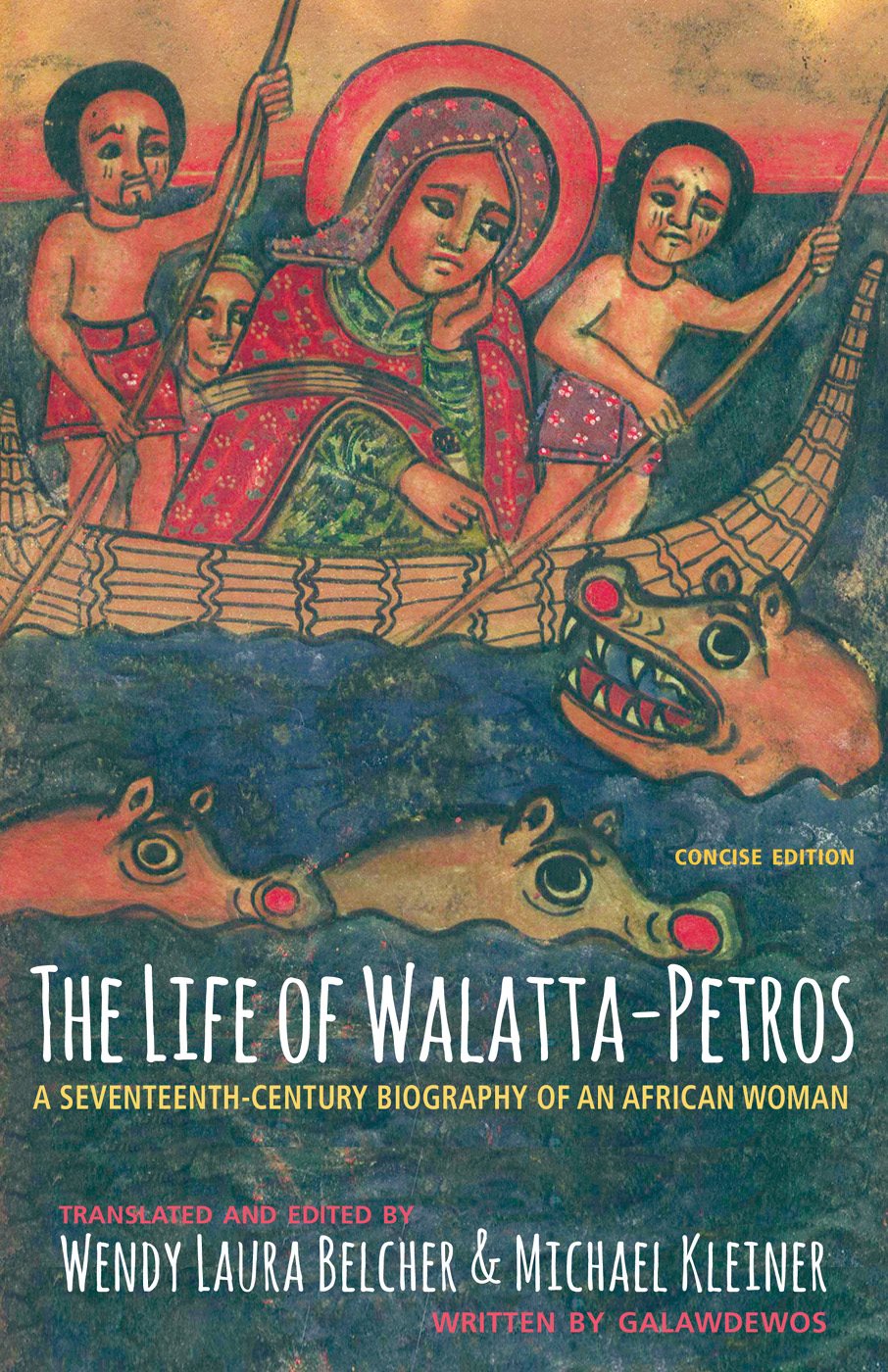

Cover art: Walatta Petros counting the hippos teeth on Lake Tana

(SLUB Dresden / Digital Collections / 3.A.6718)

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Control Number 2018935646

ISBN 978-0-691-18291-9

eISBN 9780691188898 (ebook)

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

CONTENTS

vii

xx

xxiii

xxv

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Wendy Laura Belcher

When I, one of the translators of this book, was four years old, my American family moved from rainy Seattle, Washington, to the highland city of Gondar, Ethiopia, so that my physician father could teach at a small medical college there. Over the next three years, I began to learn about the many facets of this East African country. You need to learn about them, too, if you are to understand the book you hold in your hands.

Flying low over the green Ethiopian countryside, I saw the thatched roofs of many round adobe churches. I visited a cathedral carved three stories down into the stone. I awoke most mornings to the sound of priests chanting. I learned that the peoples of highland Eritrea and Ethiopia, who call themselves the Habasha, are Christians and have been Christians for approximately seventeen hundred years, longer than most European peoples. Their church is called the Ethiopian Orthodox Church: it is not Roman Catholic, Protestant, or Eastern Orthodox. It is a special form of Christianity called non-Chalcedonian, and ancient churches in Egypt, Eritrea, Syria, Armenia, and India share many beliefs with them. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church reveres saints, about three hundred of whom are Habasha men and women who were especially holy leaders.

The college gatekeeper in Gondar patiently taught me how to write some of the several hundred characters of the traditional Ethiopian script, which looked nothing like the Latin or Roman alphabet I was studying in school. For instance, to write the sound qo you use the character , or to write the sound bu you use the character . I learned that the Habasha had been writing in the ancient African script and language of Gz () for almost two thousand years. The Habasha have used this ancient language for many centuries to conduct worship in their church services, to translate Christian and secular literature from elsewhere, and to write original texts of theology, poetry, saints lives, and history.

Hiking from our home in Gondar up the steep mountainside to an eighteenth-century stone castle, I saw men bent over their laps writing with cane pens on animal skin, called parchment. These scribes were monks who lived in one of the thousand Habasha monasteries. Habasha scribes have been producing bound manuscripts since at least the sixth century, many with lavish illustrations known as illuminations. These scribes ensured that their church and monastic libraries were rich in the most important texts, whether translations from other languages or original compositions in Gz, by copying important manuscripts from other churches and monasteries, preserving them without printing presses or cameras. Perhaps only a quarter of the manuscripts in these monastic libraries have been cataloged, much less digitized, so many of their riches are largely unknown outside their walls.

In other words, I learned at an early age that the Christianity, language, and books of Ethiopia and Eritrea had nothing to do with Europe. The book you hold in your hands will make sense if you, too, remember all this.

I introduce the book with these points because when I tell people that this book was written in Africa long ago, in 1672, their preconceptions often do not allow them to understand me. They simply cannot conceive that Africans were reading and writing books hundreds of years ago, or that some black peoples were both literate and Christian before some white peoples. They say things to me like, Wait, what European wrote this book? or Wait, in what European language was this book written? Sometimes they even correct me: Oh, I think you mean it was written in 1972. So let me say it clearly: This book was written almost three hundred and fifty years ago, by Africans, for Africans, in an African language, about African Christianity. It was not written by Europeans.

This book is an extraordinary true story about Ethiopia but also about early modern African womens lives, leadership, and passionsfull of vivid dialogue, heartbreak, and triumph. Indeed, it is the earliest-known book-length biography of an Ethiopian or African woman.

Historical and Religious Context of the Book

In the 1500s and early 1600s, Roman Catholic Jesuit missionaries traveled to highland Ethiopia to urge the Habasha to convert from their ancient form of African Christianity to Roman Catholicism. The Jesuits ultimately failed, in part due to their cultural insensitivity. They did not blame themselves, however. They blamed their failure instead on the Habasha noblewomen.

When I first read this accusation, I thought that it was simple misogyny: sure, blame the women! But the more I read, the more I began to understand that one of the earliest European efforts to colonize Africa did indeed fail in part because of African women. Many Habasha men of the court converted for reasons of state, but their mothers, wives, and daughters mostly did not. These women fought the Europeans with everything they hadfrom vigorous debate to outright murderand after a decade, the Habasha men joined them. Together, they banished all Europeans from the country. Indeed, Ethiopia became one of the few countries never to be colonized by Europeans.

The Christianity of the Habasha is different from that of the Protestants and Roman Catholics. First, their Christianity is very ascetic, meaning it is against worldly pleasures. It holds that weakening the body reduces desires and thus leads to purity. Fasting is very important; many Habasha abstain from eating animal products half of the days of the year. Monks and nuns go further, eating only one meal on those days. The faithful often engage in other ascetic practices as well, such as praying while standing in cold water, staying up all night in prayer, or living in caves. Second, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church has a doctrine of theosis, the transformation of human beings by grace. This doctrine means that human beings are not inevitably sinful but actually have the potential of becoming without sin, like the Virgin Mary, Jesuss mother. As a result, the ultimate goal of Habasha monks and nuns is to leave the human behind, in part by reducing the bodys desires to nothing. When reading this book, you will see many instances of human asceticism and holiness.

CONTENTS

CONTENTS