BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brown, Kevin. The Pox The Life and Near Death of a Very Social Disease. Sutton Publishing, 2006.

Gately, lain. Drink: A Cultural History of Alcohol. Gotham, 2009.

Harvie, David I. Limeys: The Conquest of Scurvy. Sutton Publishing, 2005.

Hempel, Sandra. The Medical Detective: John Snow, Cholera and the Mystery of the Broad Street Pump. Granta Books, 2006.

Honigsbaum, Mark. Living with Enza: The Forgotten Story of Britain and the Great Flu Pandemic of 1918. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Hurt, Raymond. Tuberculosis sanatorium regimen in the 1940s: a patients personal diary, Journal of Royal Society of Medicine, 2004, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov / pmc / articles / PMC1079536/.

Loudon, Irvine. Death in Childbirth: An International Study of Maternal Care and Maternal Mortality 1800 1950. Clarendon Press, 1992.

Olson, James Stuart. The History of Cancer: An Annotated Bibliography. Greenwood Press, 1989.

Porter, Roy. The Cambridge History of Medicine. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Porter, Roy. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity. Fontana Press, 1999.

Rocco, Fiammetta. The Miraculous Fever-Tree: Malaria, Medicine, and the Cure that Changed the World. Harper Collins, 2003.

Scull, Andrew. The Most Solitary of Afflictions: Madness and Society in Britain 1700 1900. Yale University Press, 1993.

Shaw, Anne and Reeves, Carole. The Children of Craig-y-nos: Life in a Welsh Tuberculosis Sanatorium, 1922 1959. Wellcome Trust, 2009.

Shrewsbury, JFD. A History of Bubonic Plague in the British Isles. Cambridge University Press, 1970.

Talty, Stephen. The Illustrious Dead: The Terrifying Story of How Typhus Killed Napoleons Greatest Army. Three Rivers Press, 2010.

Webb, Simon. Execution: A History of Capital Punishment in Britain. The History Press, 2011.

Chapter 1

INVESTIGATION, DIAGNOSIS, AND TREATMENT OF DISEASE

N ot all deaths are caused by disease, but a major proportion of this book is devoted to medical conditions that killed our ancestors, so its appropriate to begin with a chapter devoted to disease and healthcare.

These days we have great freedom to learn about illness for ourselves if we want to. We can read the same books and websites as our doctors, and even look at original clinical research. But it wasnt that long ago that medical knowledge was virtually the sole province of doctors who guarded it jealousy. Paradoxically, despite this protectionism a high proportion of what the medical profession thought they knew about disease before the late Victorian era was simply wrong.

Identifying Diseases

Apart from finding a cause of death in the first place (see Chapter 2), a significant problem for anyone interested in investigating the diseases that affected our forebears is the accuracy of diagnoses in former times. Its very clear that medical terms could often be used quite loosely. Some diseases have very characteristic or unique symptoms and so diagnosis is more likely to be accurate: smallpox, for example. However, in other circumstances a diagnosis might cover a multitude of ills. The man or woman in the seventeenth century who died of griping in the guts died of what? Appendicitis? A peptic ulcer? An intestinal infection? Bowel cancer?

A diagnosis might cover a range of possibilities and perhaps the most notorious of these is the word fever, which indicates an infection but what kind? The circumstances might give you clues, but without more detail one can only speculate. Similarly, the diagnosis of dropsy meant that someone had a build-up of fluid in the body, but it might have been by a variety of means heart failure or kidney disease being two principal contenders.

You should also note that some words with quite precise meanings these days might have been more mutable in the past. In our modern world the diagnosis of pleurisy means a quite particular disease of the lungs, but reading accounts of pleurisy in the past it seems as if it was sometimes used to refer to all sorts of chest complaints.

Even when there was an outbreak of an infectious disease in a community, chroniclers of the time may provide such limited detail that it is not possible to identify it reliably. In the sixteenth and late fifteenth centuries, for example, Britain was periodically ravaged by the sweating sickness. There were outbreaks in 1485, 1502, 1507, 1517, 1528, and 1551. However, it is described so scantily in contemporary sources that even now we are not sure what disease this was. The fever, joint ache and exhaustion suggest these may have been a series of severe influenza epidemics, but we will probably never know for sure. And it seems that the characteristics of an epidemic disease may change according to the strain of infectious micro-organism so the flu epidemic of 1918 killed many, many more people than that of 1889 or 1957.

What Killed Our Ancestors?

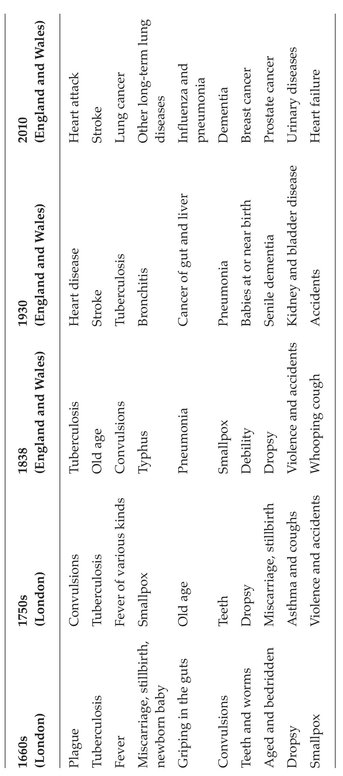

on the page opposite compares the top ten leading causes of death in random years chosen from the last five centuries. Of course its not really fair to make direct comparisons between these eras because, as noted above, the identification and classification of diseases has varied so much over the centuries. As time has progressed, diagnosis has become more accurate.

However, a general comparison is interesting. Infections such as TB, smallpox, fever, plague, typhus, and even whooping cough dominate the era before antibiotics and vaccines. The prevalence of convulsions as a cause of death probably reflects the high mortality for infants and newborn babies from infections in earlier times because fever in the very young may cause them to fit. Meningitis is another potential cause of fitting. Many of the cases of asthma and bronchitis in former times are probably what we would now call chest infections, although some may have been lung cancer.

Heart disease, cancer, and strokes only became more common in the twentieth century when people began to live long enough to develop these diseases which are more likely as people reach their late middle age. Similarly, dementia is largely a disease of the late twentieth century onwards when a high proportion of the population began to live beyond 75 years of age. Old age features as a common cause of death in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries and probably reflects a combination of all these medical conditions, but in former times many of the diseases of older adults were not diagnosed or even medically recognised.

: Top ten commonest causes off death for the years given, over the last five centuries.

(Sources: The data for the ten years of the 1660s and 1750s are from the Yearly Bills of Mortality for London; data of 1838 is derived from the second Annual Report of the Registrar-general of Births, Deaths, and Marriages ; and 1930 and 2010 data are taken from the Office of National Statistics www.statistics.gov.uk)

It is a little alarming to see that violence and accidents feature in the top ten only comparatively recently. However, technological developments in transport and safer working practices now mean that travel and the workplace are a lot safer than in previous centuries.