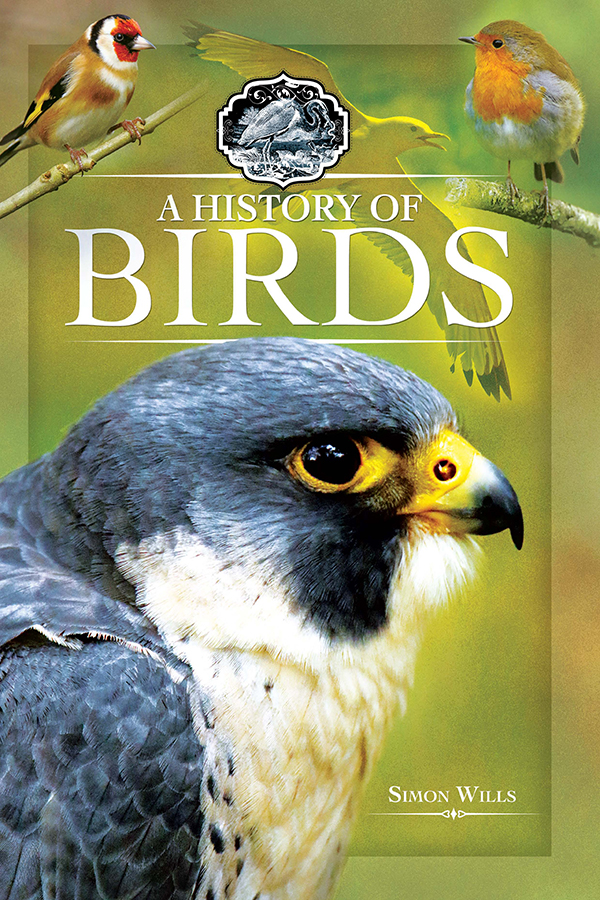

A History of Birds

To dear Dad, who loved birds and taught me so much.

I wish you had lived to see this book.

A History of Birds

Simon Wills

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword White Owl

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Simon Wills 2017

ISBN 978 1 52670 155 8

eISBN 978 1 52670 157 2

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52670 156 5

The right of Simon Wills to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas,

Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime,

Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport,

True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper,

Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press,

Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport,

Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Introduction

B irds are a very accessible part of the natural world, and always have been. I live on the outskirts of a large coastal city, and as I write this on an inhospitably cold and rainy day I can still look out the window and see birds. Theres a blackbird rooting through leaves under a bush in the garden; half a dozen gulls sail by; there are three woodpigeons huddled against the elements in the lower branches of a tree; a robin is singing somewhere close at hand despite the weather.

Our ancestors were more connected to nature than many of us today. A greater proportion of the population lived in rural areas and less land had been cleared for building, so birds were often even more visible. This is not to say that birds were not persecuted, because they were. Tudor laws labelled many birds as vermin and rewarded those who killed them; gamekeepers shot thousands of birds indiscriminately; some species were hunted for their flesh, eggs or feathers; others were killed as sport, their eggs were taken by collectors, or people wanted to keep them as pets. There were also odd beliefs about certain birds such as owls and kingfishers which encouraged people to kill them. Some species came close to extinction in the UK such as the red kite or the great crested grebe, and a few, like the great bustard, were actually exterminated.

Inevitably, and unfortunately, a history of the human relationship with birds is often a tale of avian exploitation. However, thats not the whole story. Birds have had significant symbolic meanings for all sorts of reasons. The Christian Church was an important influencer of this. When the Medieval Church labelled lapwings as deceitful, cormorants as gluttons, and jays as gossips, then this affected our ancestors attitudes to the natural world. Quite apart from this, the wider folklore around birds is rich and varied, and often it is difficult to know how some rather strange beliefs arose. It is easy to see why the eagle was regarded as an emblem of authority and power, but how did our ancestors come to believe that it kept a special stone in its nest with healing properties? Why did people believe that crows could foretell the future? In art and literature too, birds had symbolic associations that could be complex, and might vary according to the context: the peacocks beauty led it to symbolise vanity, but its allegedly incorruptible flesh meant it could also represent immortality.

Birds of all kinds have been kept as pets and human companions, from the humble sparrow to the beautiful parrots of the world. Birds were, and are, of economic significance too the meat and eggs of the chicken, the feathers of the goose that were so important for centuries as writing tools, and the enormous service that many birds perform by eating pests. There were whole careers that depended on birds for falconers, fletchers and farmers.

Birds fascinated our ancestors as much as they captivate us today. For millennia they have brightened our lives with their colours, their songs, their engaging behaviour, and their flight, which has come to symbolise freedom and inspired the portrayal of angels. Our forebears wrote poetry about birds, created music because of them, worshipped and depicted them, and even bestowed magical properties upon them. It is perhaps no coincidence that some of the oldest words in the English language are the names of birds.

The world would be a miserable place without birds, and in this book I hope to show how the relationship between us and our avian counterparts has evolved. Our modern attitudes are very much shaped by our ancestors beliefs and experiences.

Acknowledgements

S o many websites now make original historical texts and images available freely to researchers and I would like to take this opportunity to thank them, and especially the following:

British Library illuminated manuscripts: www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts ,

Internet Archive: https://archive.org/

Early English Books Online: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebogroup/

Google Books: https://books.google.co.uk/

Perseus Digital Library: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/

Wellcome Images: https://wellcomeimages.org/

University of Aberdeen for the Aberdeen Bestiary online: https://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/

Id also like to thank Scotford Lawrence, curator of the National Cycle Museum.

I am grateful to Michael Palmer of Photo Experience Days: www.photoexperiencedays.com who taught me how to use a new camera much better than any manual could have done.

Linne Matthews has been my editor at White Owl and I have really appreciated her patience, attention to detail, and kindness.

Finally, I would as always particularly like to thank my partner, B, who is so kind and supportive whenever I am writing a book. Every writer needs looking after!

Blackbird

T he name blackbird has been in use since at least medieval times, but our Anglo-Saxon forebears preferred the term ouzel (pronounced oozle). For many centuries these two words were used side by side in books of natural history the blackbird or ouzel but by the late nineteenth century it was blackbird that emerged as the dominant name.

In Scotland the bird was often known as the blackie and in certain areas of England the merle or colley, the latter probably because of its coal colour. Interestingly, eighteenth-century versions of the seasonal song The Twelve Days of Christmas describe blackbirds being sent on the fourth day:

The fourth day of Christmas

My true love sent to me:

Four colley birds,

Three French hens,

Two turtle doves

And a partridge in a pear tree.

Later adaptations seem to have changed colley birds to the more widely understood calling birds. Another set of famous verses to feature the blackbird is the nursery rhyme Sing a Song for Sixpence , which was known in the eighteenth century but may have earlier origins:

Next page