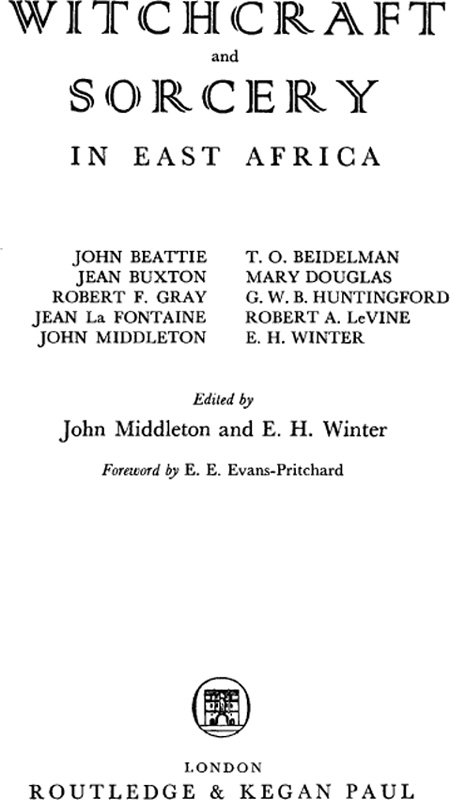

First published in 1963

Reprinted in 2004 by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, 0X14 4RN

Transferred to Digital Printing 2009

Rout ledge is an imprint of the lay lor & Francis Group

1963 Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

The publishers have made every effort to contact authors/copyright holders of the works reprinted in Routledge Library EditionsAnthropology and Ethnography. This has not been possible in every case, however, and we would welcome correspondence from those individuals/companies we have been unable to trace.

These reprints are taken from original copies of each book. In many cases the condition of these originals is not perfect. The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of these reprints, but wishes to point out that certain characteristics of the original copies will, of necessity, be apparent in reprints thereof.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Witchcraft and Sorcery in East Africa

ISBN 0-415-32556-0 (set)

ISBN 978-1-136-55152-9 (ePub)

ISBN 0-415-33073-4

Miniset: Witchcraft, Folklore and Mythology

Series: Routledge Library Editions Anthropology and Ethnography

First published 1963

by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

Broadway House, 6874 Carter Lane

London, E.C.4

Printed in Great Britain

by The Chapel River Press Ltd

Andover, Hants

Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd 1963

No part of this book may be reproduced

in any form without permission from

the publisher, except for the quotation

of brief passages in criticism

E. E. Evans-Pritchard

I HAVE been asked by the Editors and other contributors to this volume to write a brief and personal foreword to it. I have been paid this compliment in recognition of my attempt to place the study of African witchcraft and kindred topics on a scientific basis. The first results of my researches were published in Sudan Notes and Records thirty-five years ago, and it is twenty-six years since my monograph Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic among the Azande appeared. No purpose would be served by my restating the argument of that book, but I may be permitted to say that on the whole the major conclusions reached in it have been confirmed by further researches among African peoples, though these, some of which have been excellent studies, have in the intervening years been disappointingly few. This is strange, for most, perhaps all, African peoples have witchcraft or sorcery beliefsor bothin some degree, and one would have thought that they would have engaged the attention of ethnographers more than they appear to have done. All the more reason, therefore, to welcome the present volume which takes the study of witchcraft and sorcery a step forward and also provides a textbook which should be of value in anthropological departments and of interest to nonspecialists. It is not generally appreciated how much light has been shed on witchcraft ideas in general by anthropological research during the last few decades, and the present essays on the subject in a number of African societies and the critical analysis in the Introduction should help to dispel the many misunderstandings and misconceptions about it that one finds not only in popular thought but also in learned works. This is not a subject of what is sometimes called mere academic interest. Belief in witchcraft may have almost entirely disappeared in our own culture, where it died hard, but in Africa it is still very prevalent, and not only among the uneducated.

Nothing can give a student greater pleasure than to see his own work continued by a younger generation, so I conclude this short and informal note by expressing my gratification that there is now a renewed interest in a subject to the study of which I have devoted some years of my life, and by offering my thanks to the Editors and other contributors for the honour they have done me in allowing me to associate my name with theirs.

John Middleton and E. H. Winter

I

T HE subject of witchcraft and sorcery is a matter of great importance and also one on which there is a great deal of misunderstanding. Beliefs about witches and sorcerers have a world-wide distribution; in Africa their occurrence is almost universal. Although in some societies they play a very minor role in the daily lives of the people, in most it is no exaggeration to say that one cannot gain any fundamental grasp of the attitudes which people have towards one another nor can one understand many aspects of their behaviour in a wide range of social situations without a fairly extensive knowledge of their ideas regarding good, evil and causation, and their associated beliefs in witches and sorcerers. Witch beliefs have played a very important role in Western society until very recent times. The fact that most Europeans no longer hold these ideas, though, and the fact that they regard them as superstitions, products of ignorance and error, often hampers communication between Europeans and Africans. And the failure to understand the precise nature of witchcraft beliefs and, of even greater significance, the failure to understand the roles of these beliefs in the context of the lives of those who hold them, is often at the basis of nave statements that the African mind is different in some fundamental way from the European mind and in an ultimate sense incomprehensible. But these beliefs are social, not psychological, phenomena and must be so analysed.

This volume contains a number of essays in which the relevant facts from various societies are described and analysed. Since they speak for themselves we wish to devote these introductory pages to an assessment of the present status of research in this field and to suggestions concerning lines along which future inquiries could profitably be pursued.