AFRICAN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDIES OF THE 20TH CENTURY

Volume 35

WITCHCRAFT, SORCERY AND SOCIAL CATEGORIES AMONG THE SAFWA

WITCHCRAFT, SORCERY AND SOCIAL CATEGORIES AMONG THE SAFWA

ALAN HARWOOD

First published in 1970 by Oxford University Press for the International African Institute.

This edition first published in 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1970 International African Institute

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-8153-8713-8 (Set)

ISBN: 978-0-429-48813-9 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-59414-2 (Volume 35) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-48901-3 (Volume 35) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

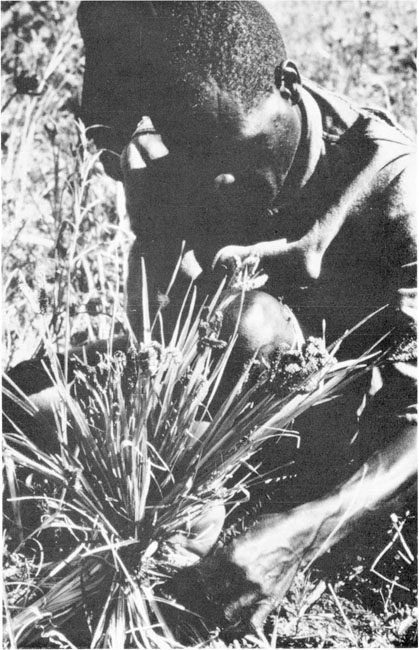

Headman cutting a special sheaf of millet which is reserved as seed for the following year

WITCHCRAFT, SORCERY, AND SOCIAL CATEGORIES AMONG THE SAFWA

-------------

ALAN HARWOOD

Published for the

International African Institute

by the

Oxford University Press

1970

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Preface

- Itonga and witchcraft, medicines and sorcery:

a comparative view of Safwa beliefs

Oxford University Press, Ely House, London W. 1

GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON

CAPE TOWN SALISBURY IBADAN NAIROBI LUSAKA ADDIS ABABA

BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI LAHORE DACCA

KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE HONG KONG TOKYO

International African Institute 1970

Printed in Great Britain

by Ebenezer Baylis and Son, Ltd.

The Trinity Press, Worcester, and London

LIST OF PLATES

LIST OF TABLES

LIST OF FIGURES

LIST OF MAPS

I came to write about witchcraft and sorcery among the Safwa by a very indirect route. In the spring of 1962 I was awarded a Pre-Doctoral Research Training Fellowship from the Social Science Research Council (U.S.) to prepare a general ethnography of the Funga, a group located in the Livingstone Mountains of what was then the Southern Highlands Region of Tanganyika. I had selected the Kinga partly because of their scanty coverage in the ethnographic literature but mainly because I was interested in problems of swidden agriculture in a mountain environment.

About six weeks before leaving for East Africa, I learned that another anthropologist, Dr. George Park, had already begun research among the Kinga. On arrival, I met with Park and Dr. Derek Stenning, who was then Chairman of the East African Institute of Social Research. For a number of reasons, methodological and financial, we agreed that it was not advisable for two anthropologists to locate among the Kinga. This decision led me to reconnoitre neighbouring peoples. I surveyed the Pangwa, Safwa, and very briefly the Sangu. Since Safwa territory contains mountains, plains, extinct volcanic craters, and other ecological niches which augured well for a study of agricultural techniques, I chose to settle with this group.

Although I gathered material on Safwa agricultural practices (some of which I have reported briefly elsewhere, Harwood 1964), the Safwa themselves led me to another fascinating area of their cultureideas about the cause of disease and the relationship between these ideas and interpersonal disputes. In this roundabout way I came to write the dissertation on witchcraft, sorcery, and social classification which forms the basis of this book.

Altogether I spent seventeen months among the Safwa from early November 1962, to late March 1964. Approximately fifteen months of this time were spent in one community, which I call Ipepete, and it is largely the kindness and generosity of the people of this settlement which made my field work possible. Since this book often discusses family and other disputes which many of my former neighbours would not want publicized, I have protected their identities by changing all personal names and the names of all communities.

Ipepete, like all Safwa communities, is a group of dispersed compounds and houses. I lived in one of a unique cluster of recently built, rectangular, mudbrick houses, the rest of which were inhabited by young Safwa men and their wives. One of these young men, the son of the local headman, served as my first assistant and teacher of the Safwa language. With his and others help, I eventually attained sufficient command of the language to be able to conduct my daily activities and question people without the help of an interpreter. I nevertheless went to important interviews or events with an English-speaking assistant who could provide clarification if needed. I did not attain sufficient mastery of Safwa to comprehend fully conversations in which I was not directly involved.

In the early days of my field stay I spent much of my time with young men about 15 to 30 years of age. They and children proved the most patient language teachers. The youths who sought me out tended to be those who had spent some time among strangers at mines either in South Africa or Zambia. Because they were familiar with some features of my worldradios, movies, magazines, African geographyas well as the indigenous world of ancestors, kin responsibilities, and hoe farming, they helped me in the transition to this latter world. In time I talked more and more with the older adults (the 40 to 60 year olds) who were committed to this world, and it was largely they who furthered my understanding of witchcraft and sorcery. To them, thank youendaga, mwasalipa.

I would like to thank the Social Science Research Council (U.S.), which supported my field research, and the U.S. Public Health Service, which awarded me a grant while I was writing up the material. I am also indebted to Professor Harold Conklin for his influence and encouragement during my anthropological training.

In preparing this study for publication, I am particularly grateful for the helpful comments of Professors Morton Fried, Terence Hopkins, John Middleton, and Aidan Southall, all of whom read the manuscript at one or another stage of completion. To them I owe many improvements. I would also like to thank Dr. David Crabb for advising me on Safwa orthography and Mr. Donald Miller for preparing the maps and diagrams. I am indebted to the International African Institute for undertaking the publication and to Miss Barbara Pym for her editorial assistance.