Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

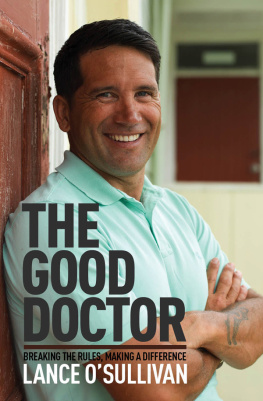

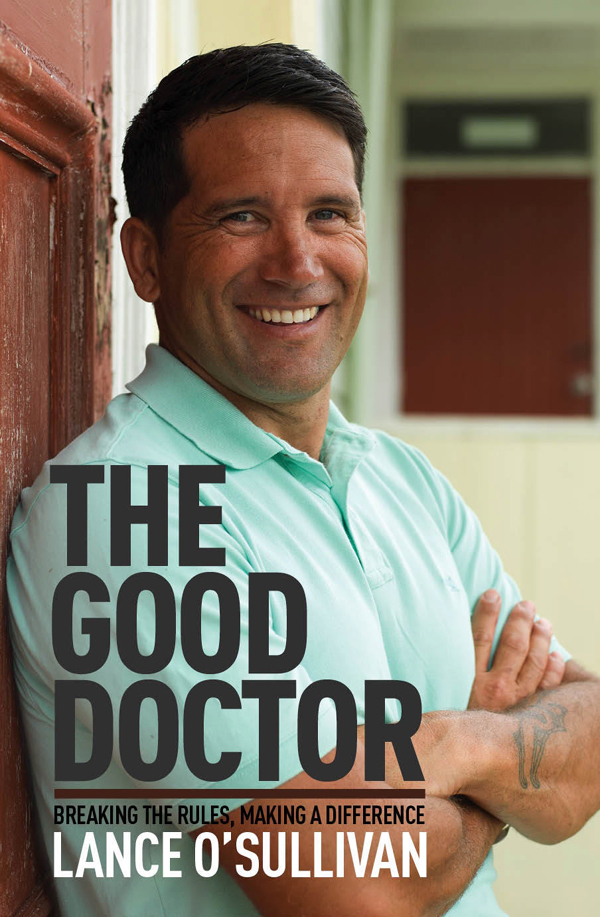

Text and photographs copyright Lance OSullivan 2015, unless otherwise credited.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Let the conversation begin...

Find out more about the author and discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.nz

INKEI TE MHIO KOE KO WAI KOE, I ANGA MAI KOE I HEA, KEI TE MHIO KOE. KEI TE ANGA ATU KI HEA

IF YOU KNOW WHO YOU ARE AND WHERE YOU ARE FROM, THEN YOU WILL KNOW WHERE YOU ARE GOING

Prologue

Making a Difference

TWO PATHWAYS DIVERGE

A couple of teaching staff were chatting in the secondary school staffroom as they got things ready for the lunchtime rush. As one of them poured cups of tea, a thought struck her.

Whatever happened to that boy, Lance OSullivan? I suppose hes in jail by now?

A third person, who had been my mums next-door neighbour, overheard the conversation and couldnt resist. Oh, she interrupted. Lance is at medical school.

You could have heard a pin drop.

Everyone thought we OSullivan boys were going to jail. Thats what a friend of my brothers told us, and I guess it looked that way for a while, more for me than my younger brother, Matt. We were easy marks the half-caste kids of a solo mother. Matt was high-spirited and mischievous, but by the time he got to college he was a good student. There were probably times he was tarred with the same brush as me, though, because for a few years there my future didnt look bright. I was in serious danger of becoming a statistic: a Mori boy who was failing at school and, at the age of 12 or so, had already had a brush or two with the law. By 15 Id been expelled from two schools and I had an attitude problem that was getting me into some pretty vicious fist fights.

No ones going to tell me what to do.

I was called a nigger by my Pkeh neighbours, and a honky by my Mori cousins. I was a pretty confused kid. Was I black or was I white? I was looking for my identity in all the wrong places among the troublemakers at school, my alcoholic father. Which way was my life going to go? The path I was on was leading me straight to failure.

The one thing that got me off that path and onto the right track was being able to make a different choice about my identity. I found myself, at the age of 15, in a Mori environment for the first time, surrounded by strong, positive Mori role models, with te reo flying all around me. I discovered there is a lot to be proud of in being a Mori man and then I found this huge thirst to know more.

Thats why I think my story is worth telling. I hope itll inspire other young people with the idea that you dont have to follow pathways that seem set in stone. You can dream and achieve. My story is one of making a go of things and also a story about the value of knowing who you are, and of contributing to the community and the country. Its about help coming along at just the right time.

As I learned more about my own identity and began to find out about the history of my people, and the realities of life for many Mori today Mori men, for instance, have a life expectancy thats 14 years less than non-Mori men; rheumatic fever, a lethal but preventable disease, has almost disappeared in Pkeh children but our rates for Mori and Pasifika children are among the highest in the developed world I was filled with a passion to help improve the situation for my people.

When I found my identity, I also found my self-belief and my purpose. But I still had no idea how I was going to make my contribution.

I could be a doctor, they said. But I knew no doctors. No one in my family not one of hundreds of cousins on my dads side had ever been to university, let alone medical school. But against all the odds, Id gone from being a drop-out to runner-up dux of Hato Petera College, and my future was now looking bright. My schoolteachers were encouraging me to think big: doctor, lawyer.

But medical schools really hard! Smart people go there people who arent like me.

Then one day my Auntie Nellie, my fathers sister, called me.

Nephew, she said that was how she talked to me Nephew, Id like you to come with me to a hui.

I was 17, and the hui was on a Friday night.

What is it, Auntie? I asked cautiously.

Its a hui on rongo Mori, traditional Mori healing.

OK, I said reluctantly.

I could see that I might find it useful, since people were saying I could be a doctor. So I went along to a marae in Mngere called Mataatua and its lucky I did, because something really important happened. A young Mori man stood up to address the hui and it turned out he was a doctor. He was in his mid-twenties, he spoke fluent Mori, elegant English. He was smart, he was charismatic, and he captured my heart. I couldnt stop staring.

Wow, I thought. Im going to be like you. Im going to be a Mori doctor who can stand and speak with a lot of confidence and snare peoples attention.

I was inspired, and I was aware of a thought leaping into life inside me:

I want to inspire others just like youve inspired me.

That man was in my life for 45 minutes when I talk about him in presentations I call him the 45-minute Man but he changed my life. To be like him, that goal was sitting at the peak of the maunga I was going to climb.

The time I spent listening to him had a huge impact on me, and it taught me that if I could give an hour to others, as he did, who knows what amazing things could follow. When we lead by example, we can have a big effect on the world.

So it was settled: thats what I was going to do. I was going to show leadership like him. I was going to go to medical school and somehow make a contribution to my people.

He was the first Mori doctor that Id ever seen. I didnt know they existed. I didnt know it was possible. And I get told that now, too, even 25 years later.

We didnt know there were any like you.

Fast forward about 15 years and Im in Kaitia running echocardiograms on schoolchildren as part of a Heart Foundation screening programme to detect heart disease caused by undiagnosed rheumatic fever. Of 870 kids, we found eight whose heart valves were diseased. Seven of them will have to have painful monthly penicillin injections until theyre 21 (and at least one of those, a young boy who has quite bad heart damage, is so afraid of the nurse with that needle that he now refuses the treatment, meaning he will almost certainly experience cardiac problems in his twenties and thirties).