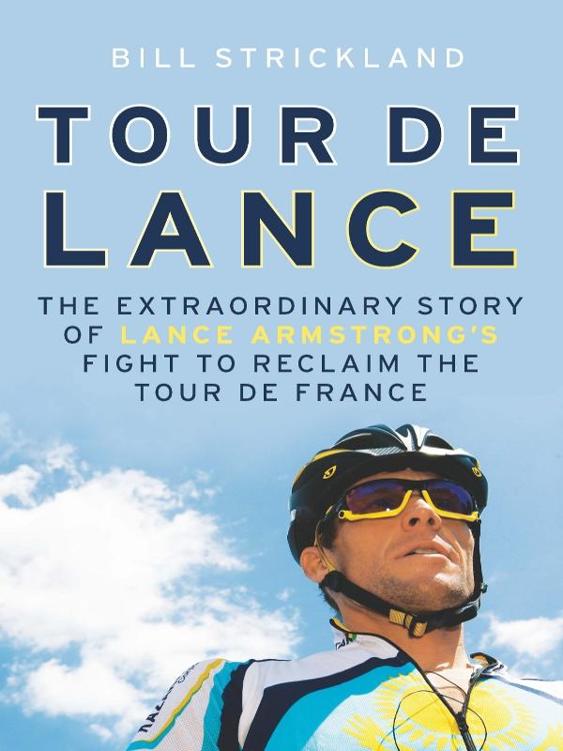

TOUR DE LANCE

ALSO BY BILL STRICKLAND

We Might as Well Win (coauthored with Johan Bruyneel)

Ten Points

The Quotable Cyclist

TOUR DE LANCE The Extraordinary Story of Lance Armstrongs Fight

to Reclaim the Tour de France BILL STRICKLAND

First published in Australia and New Zealand by Allen & Unwin in 2010

First published in the United States in 2010 by Harmony Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Copyright Bill Strickland 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

| Phone: | (61 2) 8425 0100 |

| Fax: | (61 2) 9906 2218 |

| Email: | info@allenandunwin.com |

| Web: | www.allenandunwin.com |

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.librariesaustralia.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74237 307 2

Design by Gretchen Achilles

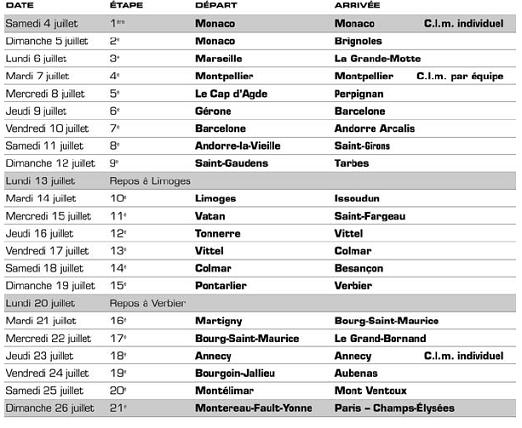

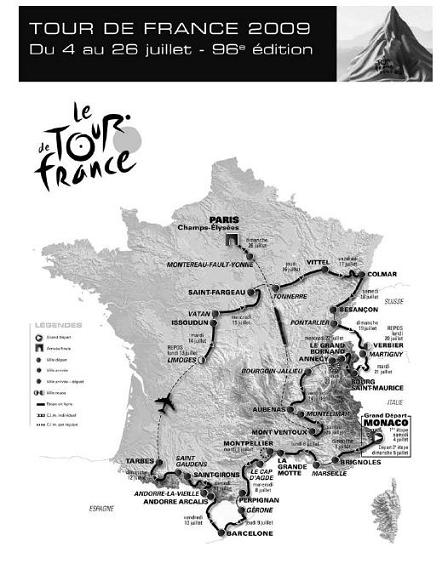

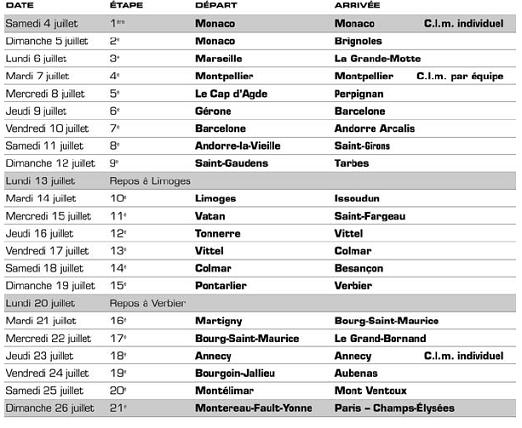

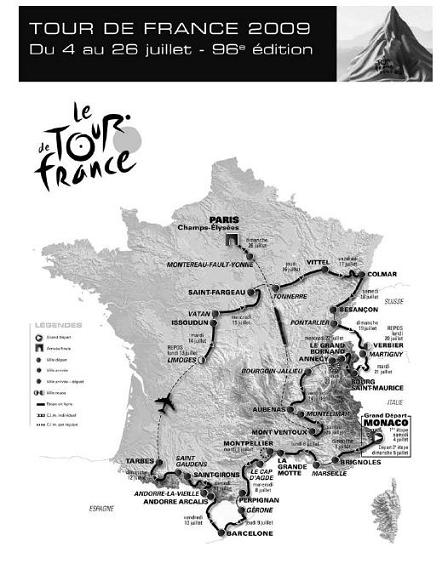

2009 Tour de France map courtesy of ASO (American Sports Organisation)

Insert photographs copyright James Startt

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Beth,

my rhythm

CONTENTS

Character

on its way toward destiny

my favorite kind of helplessness. STEPHEN DUNN , Irresistible

H ere he is, Lance Armstrong. And there he goes: a blue-and-yellow-and-white figure on a black-and-yellow bike streaking over the gray surface of a road in Monaco late on a summer morning, the suns yellow pale in comparison to the shoulders of his jersey, the skys blue like nothing more than the original idea for the magnificent tones that wrap around his back and legs. He is bent forward and low over the top of the bike, arcing himself butt to fingertips from the saddle to the handlebar like an airfoil, like a thing dreamed of and studied in prototypes and finally forged in perfection to round out the top profile of a bicycle in a way that makes it slippery against the forces of friction.

His feet each make a complete circle about 120 times a minute, or two revolutions a second, which is roughly the same cadence Usain Bolt maintains for 9.71 seconds to win a gold medal. Today, Armstrong will sustain this furious whirling of his feet for around 20 minutes. Some days he does it for six hours. This maelstrom occurs with a precision that if visible would surprise the untrained eye, and contains a daintiness that the sports acolytes would find embarrassing. At the lowest point of a stroke Armstrongs foot lies almost flat on the pedal. As his leg begins to pull up on the pedal his foot starts to point down, and this oppositional change continues until his foot is almost vertical, a ballerinas pose that is imperceptible as it appears and vanishes in around one-eighth of a second. Then his foot comes over the top of the pedal stroke. His heel drops, and the muscles of his leg begin pushing the pedal forward with visible force. The calves have ripped themselves in half lengthwise by their own development, a deep V cut into their center in a muscle configuration peculiar to cyclists. Whatever tissue that was not useful for the execution of this pedal stroke has been eroded by years and years and years of miles and miles and miles of training. The thigh is its equal on a larger scale, the glutes and the hamstrings also, with everything extraneous scooped away. It is an act of violence and disregard, the way these muscles ram the foot forward then plunge it down to the lowest point of the revolution to start the whole stroke over. Twice a second Lance Armstrong does this with each leg, while its opposite leg in unthinking synchronicity performs the counter-movement, the frightening muscular explosion on one side while the ballerinas pose is struck on the other.

His upper body betrays none of this effort. It floats placid above the dervish of his legs, covered in a skinsuit that appears more skin than suit in the way it ripples with every contour of his physique. The fabric of this suit draws sweat from his skin out to the air to be evaporated in seconds and cool him, and it also has been blended and tailored in such a way to soothe the swirling air into a smooth flow that diverges around his body instead of battering against it. The suit was custom-made, yet between the measuring and todays Stage 1 time trial of the 2009 Tour de France, Armstrong shed more weight than anyone could have guessed. He is lighter for this Tour than he has ever been, even in his prime from 1999 to 2005, and there are wrinkles around the armpits and the backs of his quads where the material sags a little, unable to conform to the new concavities Armstrong has carved into his body. The zipper of the skinsuit is undone a few inches, a casual act that doubtless breaks the hearts of the suits designers and aerodynamic experts, who might have worked months to eliminate such minuscule amounts of drag. Snaking out of the unzipped collar is a black cord that leads to a radio earpiece taped into Armstrongs right ear with white medical tape gone a little greasy from some mechanics fingertips. The pull tab of the zipper swings as Armstrong pedals, its metronomic motion coming not from his upper body, which remains still, but from a slight rocking of the entire bike itself.

This minor sway does not affect his steering. Any disruption it might cause is absorbed somewhere during its transmission from his torso through his arms, which are bent at the elbow nearly 90 degrees, then stretched out along aero bars that protrude in front of his bike. One black-gloved hand lies unmoving on each bar, and if you could touch these hands you would be startled by how relaxed they are. He is not clenching the bar but resting his fingers around it, the way someone might lightly palm but not grip a handrail on a set of familiar stairs. To clench would be to direct energy into something not necessary for propelling his bike forward. His hands move when the driver in the car behind him, his team director Johan Bruyneel, speaks to him through the earpiece and tells him to shift or to change his speed or set up for a corner or a climb or a long, straight flat section of the course. When this happens Armstrongs fingers snap forward and make a subtle but crisp movement that clicks a lever on the end of the bar, which pulls a twined steel cable that moves the rear derailleur either right or left, dragging the chain onto a different cog.

Next page