For my mother,

Hazel Cooper

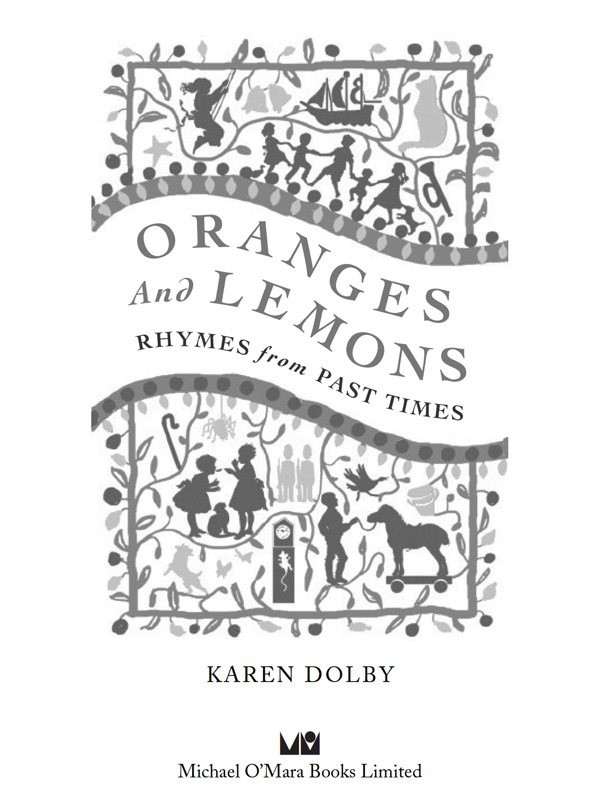

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Michael OMara Books Limited 9 Lion Yard Tremadoc Road London SW4 7NQ Copyright Michael OMara Books Limited 2012 All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 978-1-84317-959-7 in hardback print format ISBN: 978-1-84317-975-7 in EPub format ISBN: 978-1-84317-976-4 in Mobipocket format Designed and typeset by K DESIGN, Winscombe, Somerset www.mombooks.com

When I came to write this book, I was surprised how clearly I could remember the words to many of the nursery rhymes I learned as a young child. The verses are apparently effortlessly fixed in my memory when it seems so easy to forget much of what Ive carefully tried to learn since.

For many of us, nursery rhymes are the first verses we hear, the first lines we learn by heart. They are interwoven with our earliest memories, whether miming the actions, learning to count, or simply enjoying the rhythm and sound of the words and lines. I can still remember the book of rhymes I looked at with my mother when I was very small, and picture the illustrations. I think this is true for many people and probably the reason why nursery rhymes are so fondly remembered and firmly lodged in our consciousness. The majority of the rhymes are anonymous, part of an oral tradition of folk memories passed on by word of mouth from generation to generation. They were first written down on broadsheets and in chapbooks, often little more than pamphlets, containing poems, stories, songs, and religious tracts, illustrated with engravings which made them popular with the many people at the time who were unable to read.

In most cases, nursery rhymes were only collected into published books from the eighteenth century onwards when a growing interest in childrens literature developed. The first anthology was Tommy Thumbs Pretty Song Book, which was printed in London around 1744. Others quickly followed. Specific melodies or games were also often associated with the rhymes and these were very widely known. But nursery rhymes are so much more than simple verses for children. Some have a decidedly sinister edge, which is perhaps why they have been used to such chilling effect in horror films.

Many are very old, dating back to the Elizabethan era, and some even further to medieval ballads, or classical odes. They may recall past events and characters otherwise long forgotten, or parody royalty and political figures from a time when open dissent was a serious offence. Some of the oldest rhymes have the best-documented histories, for others the origins are completely hidden, and although there are theories, it is impossible to know for certain what is true and what is just a good tale. Over the centuries, the distinction between myth and history can become blurred. Perhaps thats part of their charm, and decoding the hidden meanings offers a tantalizing glimpse of the past and a fascinating insight into our social history.  The most innocent-sounding little rhymes can hide the most surprising stories: for instance, was little Jack Horner a sixteenth-century chancer who took advantage of a trusting boss and turbulent times to advance his family fortunes? And folklore suggests the rhyming couplet, When Adam delved and Eve span, Who was then a gentleman? dates from the years following the Black Death.

The most innocent-sounding little rhymes can hide the most surprising stories: for instance, was little Jack Horner a sixteenth-century chancer who took advantage of a trusting boss and turbulent times to advance his family fortunes? And folklore suggests the rhyming couplet, When Adam delved and Eve span, Who was then a gentleman? dates from the years following the Black Death.

Referring to the equality known in the Garden of Eden, it was used as a rally call to revolution, a cry for freedom from the rigid feudal system, which helped to fire the movement leading to the Peasants Revolt in 1381. However, although its a popular idea, Ring-A-Ring O Roses is probably not linked to the Great Plague. It may not even be particularly old, not appearing in the earliest anthologies. There are references to nursery rhymes in Shakespeare and Pepys, in eighteenth-century pantomimes and early scientific studies. There are remarkable similarities between the rhymes told in Britain, America, and throughout Europe. Oranges And Lemons is a collection of the most well-known and best-loved nursery rhymes, along with some that may be less familiar. Oranges And Lemons is a collection of the most well-known and best-loved nursery rhymes, along with some that may be less familiar.

The book looks at the history of the rhymes and the controversies surrounding their origins. Although children throughout the ages demand that rhymes be told again in exactly the same way, variations in wording have evolved. The versions I have included are the ones I remember, the rhymes I have tried to pass on to my own children, and I apologize if they differ from the versions you knew and loved.

Thanks to everyone who passed on their favourite rhymes and stories, and to the editorial and design teams at Michael OMara, especially Louise Dixon and Patrick Knowles.

Alphabet rhymes have always been popular as a fun way to help children learn to read, and their vivid imagery lends itself to lively illustrations. Counting-out rhymes are remarkably international and many are variations of the same ancient codes.

Used as a formula for choosing who is it in childrens games, their apparent simplicity may hide a more sinister past. A Was an Apple Pie A was an apple pie; B bit it, C cut it, D dealt it, E eat it, F fought for it, G got it, H had it, I inspected it, J jumped for it, K kept it, L longed for it, M mourned for it, N nodded at it, O opened it, P peeped in it, Q quartered it, R ran for it, S stole it, T took it, U upset it, V viewed it, W wanted it, X, Y, Z, and ampersand All wished for a piece in hand.  This simple rhyme, teaching the alphabet, has a long history and was known in the reign of Charles II, when letters A to G were quoted in a religious pamphlet. The vowels I and U are also missing from other early versions as no distinction used to be made between the letters I and J, and U and V when written as capitals. It was published in a childrens spelling book in 1742 in London, and first printed in America in 1750 in Boston. After that, it often appeared in eighteenth-century chapbooks and by the beginning of the nineteenth century there were many variations.

This simple rhyme, teaching the alphabet, has a long history and was known in the reign of Charles II, when letters A to G were quoted in a religious pamphlet. The vowels I and U are also missing from other early versions as no distinction used to be made between the letters I and J, and U and V when written as capitals. It was published in a childrens spelling book in 1742 in London, and first printed in America in 1750 in Boston. After that, it often appeared in eighteenth-century chapbooks and by the beginning of the nineteenth century there were many variations.

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Michael OMara Books Limited 9 Lion Yard Tremadoc Road London SW4 7NQ Copyright Michael OMara Books Limited 2012 All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 978-1-84317-959-7 in hardback print format ISBN: 978-1-84317-975-7 in EPub format ISBN: 978-1-84317-976-4 in Mobipocket format Designed and typeset by K DESIGN, Winscombe, Somerset www.mombooks.com

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Michael OMara Books Limited 9 Lion Yard Tremadoc Road London SW4 7NQ Copyright Michael OMara Books Limited 2012 All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 978-1-84317-959-7 in hardback print format ISBN: 978-1-84317-975-7 in EPub format ISBN: 978-1-84317-976-4 in Mobipocket format Designed and typeset by K DESIGN, Winscombe, Somerset www.mombooks.com

The most innocent-sounding little rhymes can hide the most surprising stories: for instance, was little Jack Horner a sixteenth-century chancer who took advantage of a trusting boss and turbulent times to advance his family fortunes? And folklore suggests the rhyming couplet, When Adam delved and Eve span, Who was then a gentleman? dates from the years following the Black Death.

The most innocent-sounding little rhymes can hide the most surprising stories: for instance, was little Jack Horner a sixteenth-century chancer who took advantage of a trusting boss and turbulent times to advance his family fortunes? And folklore suggests the rhyming couplet, When Adam delved and Eve span, Who was then a gentleman? dates from the years following the Black Death.

Alphabet rhymes have always been popular as a fun way to help children learn to read, and their vivid imagery lends itself to lively illustrations. Counting-out rhymes are remarkably international and many are variations of the same ancient codes.

Alphabet rhymes have always been popular as a fun way to help children learn to read, and their vivid imagery lends itself to lively illustrations. Counting-out rhymes are remarkably international and many are variations of the same ancient codes.  This simple rhyme, teaching the alphabet, has a long history and was known in the reign of Charles II, when letters A to G were quoted in a religious pamphlet. The vowels I and U are also missing from other early versions as no distinction used to be made between the letters I and J, and U and V when written as capitals. It was published in a childrens spelling book in 1742 in London, and first printed in America in 1750 in Boston. After that, it often appeared in eighteenth-century chapbooks and by the beginning of the nineteenth century there were many variations.

This simple rhyme, teaching the alphabet, has a long history and was known in the reign of Charles II, when letters A to G were quoted in a religious pamphlet. The vowels I and U are also missing from other early versions as no distinction used to be made between the letters I and J, and U and V when written as capitals. It was published in a childrens spelling book in 1742 in London, and first printed in America in 1750 in Boston. After that, it often appeared in eighteenth-century chapbooks and by the beginning of the nineteenth century there were many variations.