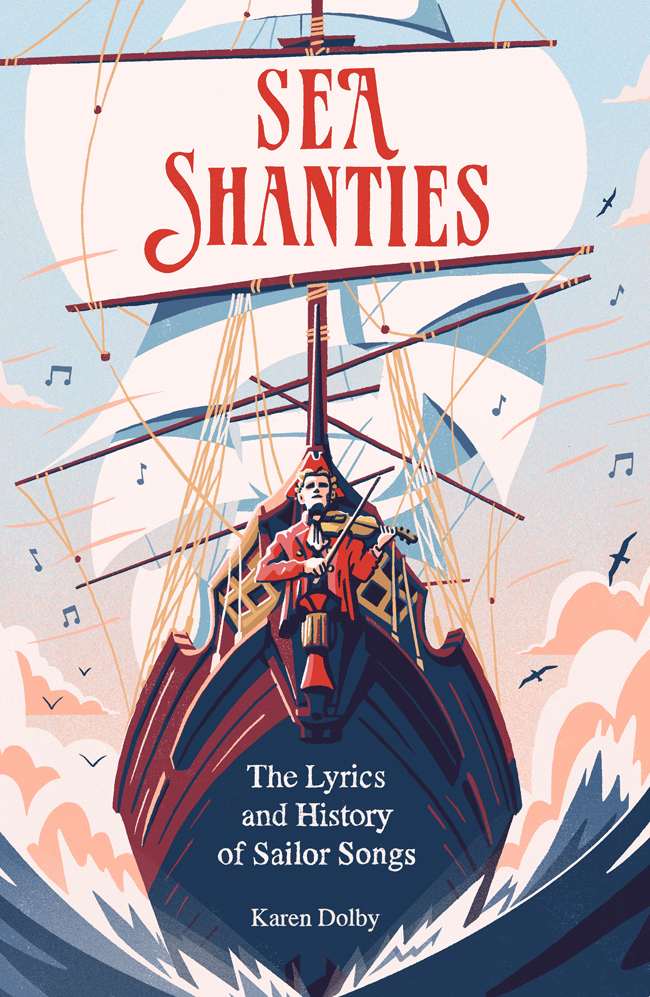

Sea

Shanties

Also by Karen Dolby

Oranges and Lemons

Historys Naughty Bits

Auld Lang Syne

The Wicked Wit of Queen Elizabeth II

The Wicked Wit of Prince Philip

My Dearest, Dearest Albert

The Wicked Wit of Princess Margaret

The Wicked Wit of the Royal Family

Queen Elizabeth IIs Guide to Life

For my father, John Cooper

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Michael OMara Books Limited 2021

The shanties in this book are historical texts and do not represent the opinions of the publisher or the author.

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78929-376-0 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78929-377-7 in ebook format

www.mombooks.com

Illustrations by Aubrey Smith

CONTENTS

In December 2020, when Nathan Evans posted his version of Wellerman on TikTok, he had no idea he was about to take the internet by storm. Two months later, his post had over six and a half million views, he had a recording contract and had quit his job as a postman. The SeaShanty hashtag itself had a staggering 1.6 billion views, with the phenomenon reported globally, usually accompanied by a photo of a lads night out, singing a sea shanty, often their own rendition of Wellerman.

Perhaps it shouldnt be so surprising. Sea shanties were intended to be catchy, with lyrics and melodies that got into your head and stayed there. They were meant to inspire and invigorate, designed to help sailors with hard, repetitive tasks aboard merchant sailing ships away at sea for months at a stretch. And in the great age of sail in the nineteenth century, sailors needed all the help they could get. Life was brutal and hard. Shanties were initially popular with British and European crews, but spread internationally. Their subject matter was wide ranging, drawing on folklore, marches, and popular songs adapted on ship to match the task in hand with rhythmical lyrics and a lot of humour. To call them bawdy is an understatement and most fall a long way short of modern standards of political correctness. They were sung without instruments, usually led by a strong-voiced shantyman. Having a good singer on board was said to be worth at least a couple of extra hands, and shantymen could expect special privileges, including lighter duties or an extra ration of rum.

Shanties were sung a cappella, without accompaniment for the most part, while the crew worked to complete a task. However, musical instruments were often played on board during the sailors downtime. Stringed fiddles, most often violins, accordions and fifes small, high-pitched woodwind instruments similar to piccolos as well as tin whistles, were all played to accompany the men as they danced or sang forebitters and sea songs.

Herman Melville, the well-known author of Moby Dick, spent five years as a sailor at sea in the 1840s and in his semi-autobiographical novel, Redburn, wrote:

I soon got used to this singing, for the sailors never touched a rope without it. Sometimes, when no one happened to strike up, and the pulling, whatever it might be, did not seem to be getting forward very well, the mate would always say, Come men, cant any of you sing? Sing now and raise the dead It is a great thing in a sailor to know how to sing well, for he gets a great name by it from the officers, and a good deal of popularity among his shipmates. Some sea captains, before shipping a man, always ask him whether he can sing out at a rope.

Shanties are work songs, sung to relieve boredom, to amuse, and with the very specific purpose of assisting sailors to perform the many heavy, physical, monotonous jobs that had to be carried out daily on a ship. They draw on the very basic need for rhythm. People have always hummed, whistled and sung as they laboured. Sailors who needed to match one anothers stroke and to function as a unit relied on the shantys rhythm to help them keep tempo when working together so that everyone knew the exact moment when extra effort was needed, increasing efficiency.

On board sailing ships there were two main types of physical labour hauling and heaving, pulling and pushing in land parlance. Hauling shanties were used when pulling ropes to hoist and lower sails and flags, while heaving shanties were sung particularly beside the capstan or windlass to raise or drop the anchor or when moving heavy weights. The key to both was that everyone hauled or heaved simultaneously at the crucial point. There was a third category of song, not connected to a specific job, but a vital part of the sailors working day, sung in the precious downtime when chores were done. These sailor songs are known as forebitters, or focsle shanties after the forecastle, the deckhouse where the sailors had their living quarters.

Although the origins of some may be much earlier, the singing of sea shanties was at its height during the age of the merchant sailing ships in the nineteenth century. The forty years of conflict that began with the American Revolutionary War in 1775 and continued through the Napoleonic Wars had made a battleground of the Atlantic Ocean, along with the eastern seaboard of America and much of Europe. This finally ended with the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, and the way was opened for trade and travel. This increased the demand for speedier ocean crossings and new-style three-masted, square-rigged clippers were developed. While the frequency of sailings and the size of the ships increased, crew numbers remained largely unchanged. This meant longer hours, harder work and even harsher conditions for the sailors. It was against this background that sea shanties developed.

The word shanty itself seems to have been adopted around the middle of the nineteenth century. Sometimes called chanty or chantey, especially in the US, the word may be a derivation of the French chanter, to sing, although chant was commonly used for songs in Britain from the Middle Ages.

Shanties were sung on board the merchant vessels and packet ships that criss-crossed the Atlantic and went on to make the perilous voyage around Cape Horn to the western coast of the Americas, trading goods and carrying passengers seeking adventure and a better life across the Western Ocean. Apart from a couple of notable exceptions, shanties were not sung on either Royal Navy or US Navy ships, where instead, a strict system of signals, codes and rules was operated.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, wooden sailing ships were being replaced by iron and steel. Steam engines and propellers made sails and paddles redundant and there was not the same need for manpower; sea shanties thus no longer served the same important work purpose on board ship. It seemed the songs themselves might well be forgotten by everyone except for a handful of seamen who had worked on the tall ships in their heyday. Fortunately, folklorist song collectors such as Cecil Sharp, Joanna Colcord, Captain Whall and, most importantly, the last working shantyman Stan Hugill, among others, were determined to preserve this musical tradition. They recorded veteran sailors, printing and preserving shanty lyrics and music, often for the first time ever.