INEQUALITY

First published 2006 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2006 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Classic readings in race, class, and gender / edited by David B. Grusky and Szonja Szelnyi.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8133-4330-3 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8133-4330-5

1. Equality. 2. Social stratification. 3. Social classes. 4. Race. 5. Sex role. I. Grusky, David B. II. Szelnyi, Szonja, 1960

HM821.C584 2006

305.01dc22

2005028911

ISBN 13: 978-0-8133-4330-3 (pbk)

For Bob Hauser

List of Tables and Figures

The main rationale for publishing an anthology of classic readings is that doing so frees instructors and other scholars from the time-consuming and routine task of assembling the readings themselves. It is unlikely, we think, that such a task is regarded by many as an attractive one, especially because there is rather little room for creativity or discretion in making the selections. To the contrary, our recent analysis of graduate and undergraduate syllabi in inequality courses revealed that instructors across the country are assigning much the same classics, almost as if some invisible hand guided them. That is, just as high school teachers of U.S. literature find themselves obliged to assign Hemingway, Faulkner, Steinbeck, and Fitzgerald, so too instructors of graduate and undergraduate inequality courses evidently find themselves obliged to assign Marx, Weber, Wilson, and Bourdieu (among others). Whatever our personal tastes or preferences might be, these classics have become part of the intellectual world in which we live, and any student who is to be inducted into that world simply must know of them. There are accordingly real economies to be had in owning up to the standardization of our syllabi and centralizing the task of assembling the classics.

If there is much consensus on the classics, it is coupled, however, with an equally striking dissensus on how one might best cull from the massive contemporary literature on inequality. In our analysis of inequality syllabi, we found that the various contemporary pieces that are chosen to supplement the common core are quite idiosyncratic and betray a host of differing viewpoints about the areas or approaches that are most important, most likely to yield a payoff in the future, or most appropriate given the interests or needs of the students being taught.

It was precisely this combination of consensus and dissensus in inequality syllabi that motivated Steve Catalano, our Westview Press editor, to approach us about editing a new anthology that represents exclusively the common core and foregoes the temptation to cull from the contemporary research literature. We were instantly attracted to the idea. The present reader is intended, then, to represent the classical core alone, a core that may then be supplemented with contemporary selections of the instructors choosing that presumably reflect the approach that is most appropriate for her or his students.

We of course hope that many scholars will continue to appreciate the convenience of a more comprehensive reader that combines the classics with contemporary pieces. For those scholars, we unsurprisingly recommend our own comprehensive reader, Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective (2001, Boulder, CO: Westview Press). This reader will continue to be updated at regular intervals to reflect current developments in the field. Although we stand by the contemporary readings in that anthology as a defensible, if not necessarily consensual, representation of the state of the field, we appreciate that some scholars will inevitably wish to chart a different course through the contemporary literature. We offer our new anthology for precisely those renegade scholars.

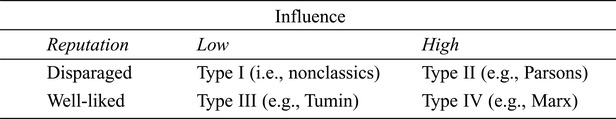

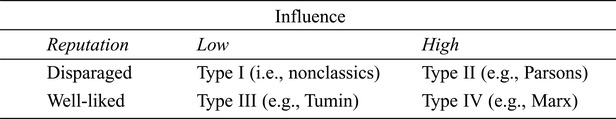

We dont mean to suggest that our selection of classics in the present anthology was a completely mechanical process lacking altogether in discretion or judgment on our end. As suggested by the , the concept of a classic is itself something of an amalgam, as it pertains at once to

(a) pieces that are widely regarded as examples of excellent scholarship (i.e., a reputational criterion), and (b) pieces that, whatever their reputational ranking may be, have decisively affected either the course of scholarship or, more spectacularly, the course of human history (e.g., Marx). Although some classics are regarded as such by virtue of a reputational criterion, others are regarded as classics not because scholars find them intellectually persuasive but because they appreciate that the world of inequality scholarship has, for whatever reason, been irrevocably influenced by them.

The vast majority of inequality scholarship fails to satisfy either of these tests and thus falls outside the space of classics (see [1,1] cell). The remaining cells in our 22 table represent, however, three quite distinct types of classics, all of which are represented in our anthology. First, the Type II classic is one which has profoundly affected the course of research and theorizing in the field, even though a sizable contingent of sociologists no longer embrace the ideas, theories, or approaches it represents. By way of example, consider the influential work of Parsons on the structure of modern stratification systems, a line of work that spawned an industry of scholarship on prestige scales and other gradational representations of inequality. Influential though it was, Parsons is hardly worshipped by contemporary inequality scholars in the way that, say, Weber still is, although no one would question the influence of Parsons. Likewise, there are very few Davis-Moore function-alists among the ranks of contemporary inequality scholars, yet presumably no one would question the influence of functionalism or the role of Davis and Moore in popularizing it.

Obversely, the Type III classic is one that most everyone still appreciates as unusually insightful or creative, yet for any number of reasons it never engendered a school of research or had substantial impact on the development of inequality research. For a classic of this sort, there is much in the way of deferential and decorative citing, but it nonetheless remains largely on the sidelines because it was introduced at an impropitious time or because it wasnt readily convertible into a research program. This category includes, perhaps, the pieces by Tumin, Turner, Veblen, and Hartmann.

Finally, the remaining pieces in our anthology arguably fall into the (2,2) cell, a category reserved for classics that deeply influenced the course of the field and are still well-received among a very broad constituency. For example, few scholars indeed would dispute the creativity and continuing relevance of the Blau-Duncan status attainment model, nor would they dispute the impact of this model on the field. We would of course like to believe that many of our selections fall into the (2,2) cell representing such doubly blessed classics.