Notting Hill Editions is an independent British publisher. The company was founded by Tom Kremer (19302017), champion of innovation and the man responsible for popularising the Rubiks Cube.

After a successful business career in toy invention Tom decided, at the age of eighty, to fulfil his passion for literature. In a fast-moving digital world Toms aim was to revive the art of the essay, and to create exceptionally beautiful books that would be lingered over and cherished.

Hailed as the shape of things to come, the family-run press brings to print the most surprising thinkers of past and present. In an era of information-overload, these collectible pocket-size books distil ideas that linger in the mind.

S ince I began practising as a psychotherapist, three quarters of my clients have been between the age of thirty-five and fifty-five. They invariably arrive for their first session in a state of depression, anxiety and uncertainty, often unsure whether to give up a profession or a marriage. In this state of near breakdown, they feel overwhelmed by some insoluble, intractable problem. As I have traversed this challenging emotional rockface with client after client I am, time and again, impressed by how these periods of inner turmoil provide us with an unmatched opportunity to review our lives and explore our personalities. We can then attempt to adapt and reshape those aspects of our nature which constrict our development, that hold back our true potential and impede our sense of well-being.

This rite of passage that we have come to call the midlife crisis has an ancient provenance. Indeed, it is the subject of the second story ever told in the earliest stirrings of Western culture. Homers Odyssey recounts Odysseuss journey home to Ithaca after the end of the Trojan Wars. As the gods test his resolve, Odysseus is beset by a multitude of calamities and temptations that during the course of his long voyage home transform him from a youthful warrior into a wise and enlightened elder.

Several thousand years later another sacred text recounts a similar rite of passage undertaken by Dante Alighieri whose Divine Comedy begins with its famous opening sentence: Midway through this life upon which we are bound, I woke to find myself in a dark wood, where the right road was wholly lost and gone. This epic story describes Dantes journey through the Inferno, Purgatory and finally into Paradise, in the company of his guide and mentor Virgil and then his muse Beatrice.

These confrontations with inner demons and outer misfortune experienced by Odysseus and Dante have numerous parallels in Western religious texts and literature. They appear in the Old Testament stories of Jonah and Job, in Christs forty days and nights in the wilderness, in St John of the Crosss Dark Night of the Soul, in Goethes drama Faust, in Tolstoys accounts of Levin and Pierres tribulations and in Eliots East Coker. The sense that inner wisdom or a feeling of enlightenment and psychological repose can only be achieved through a crisis, an ordeal or a long hazardous journey is a belief that runs through the entire tradition of Western literature, mythology and spirituality.

As with Odysseus and Dante and as with the heroes and protagonists of Goethe, Tolstoy and Eliot many of my clients who experience this ordeal meet the challenge and undergo some form of transformation. As they recover they begin a new phase of life, having resolved their central difficulties and having made the necessary adaptions to their lives, having released once dormant potentialities. The midlife crisis is invariably a unique opportunity to grow and develop our personalities in a direction that will give our lives a deeper sense of meaning and purpose, a greater sense of fulfilment and a less troubled, richer engagement with our own true natures and the world around us.

A hundred years ago Freud and Jung produced two works that were to have an immeasurable impact upon the theory and clinical practice of psychotherapy. In 1920 Freud published Beyond the Pleasure Principle, which gave a comprehensive account of his repetition theory, while in the same year Jung was writing Psychological Types, in which he described for the first time his concept of individuation. These thoughts on the psychology of midlife have running through them continual references to these two theories which stand as cornerstones of the psychoanalytic revolution, two different models of the human psyche and two contrasting approaches to the practice of psychotherapy. Both, however, shed light on why this psychological rite of passage not only appears to be a necessary experience in our emotional development but also the role of the midlife crisis as a significant part of our evolution as a species.

There are perhaps three evolutionary processes that sculpt humanitys development biological, technical and ethical evolution. Biological and technological evolution are both accepted mechanisms of human development, but I would argue that ethical evolution provides a third tier to humanitys progress which becomes essential if we are to control our species technical advance, which if left unrestrained will put our existence at risk.

If our ethical progress does not keep up with our technological progress, the planet and our species will be placed under perpetual threat. Our midlife experience therefore is crucial in providing our species with the wisdom, compassion and altruism necessary to guide humanity safely through the challenges that lie ahead.

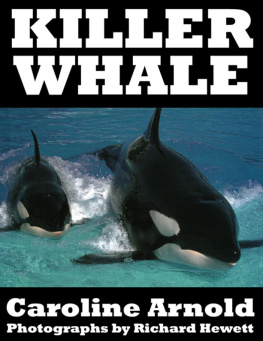

O nly two species of mammal have a post-reproductive life that lasts longer than their reproductive life. The first of these is the killer whale, or Orca. Pods of these whales are often led by very old females whose long experience and deep intuitive knowledge allow them to search out the rich grounds of food necessary to keep the pods well fed. The other species of mammal is Homo sapiens.

While the evolutionary purpose of the killer whales many years of extended life so far beyond their reproductive years seems clear, what of the Orcas human equivalent? One of the very few psychologists who has questioned why human life extends so far beyond the child-rearing years was Carl Jung.

Jung found an answer in the observation of primitive tribal cultures where elders are the protectors of the ethical and cultural wisdom of the tribe and it is this eldership which preserves the cultural heritage and the moral integrity of the community. For Jung, if a culture is to maintain its deepest, profoundest roots, while moving forward to embrace the challenges of historical and technical change, it needs to find a balance between the energy, vigour and competitiveness of those in the first half of life and the experience, dignity and wisdom of those in the second. The young braves or warriors of the tribe, with all their zest and vigour, ultimately obey the rules of the elders, and this equilibrium provides a culture with the essential balance between audacity and prudence, impetuosity and foresight, energy and moderation.

A striking example of how the wisdom of elders can constrain the belligerence of tribal warriors took place in October 1962 when humanity faced what the historian Arthur Schlesinger called the most dangerous moment in human history. On the morning of 16 October, the director of the CIA presented President Kennedy with irrefutable evidence that the Soviet Union was installing nuclear missiles on the island of Cuba, ninety miles from the US mainland. By mid-morning Kennedy had convened a meeting with his military chiefs, by the end of which the President had all but decided upon an immediate air strike against Cuba followed by a full-scale invasion of the island. Kennedy then was scheduled to have lunch with his US Ambassador to the United Nations, the veteran American politician and diplomat Adlai Stevenson. Kennedy greatly prized Stevensons experience and wisdom and had publicly stated that the integrity and credibility of Adlai Stevenson constitutes one of our greatest national assets.