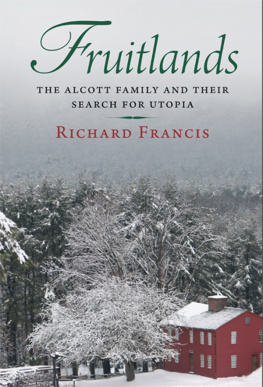

Fruitlands

Also by Richard Francis

Transcendental Utopias: Individual and Community at Brook Farm, Fruitlands, and Walden

Ann the Word: The Story of Ann Lee, Female Messiah, Mother of the Shakers, The Woman Clothed with the Sun

Judge Sewall's Apology: The Salem Witch Trials and the Forming of an American Conscience

Fruitlands

THE ALCOTT FAMILY AND

THEIR SEARCH FOR UTOPIA

by

R ICHARDF RANCIS

YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS | NEW HAVEN AND LONDON

Copyright 2010 Richard Francis

The right of Richard Francis to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office: sales.press@yale.edu yalepress.yale.edu

Europe Office: sales@yaleup.co.uk

Set in Arno Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Francis, Richard, 1945

Fruitlands: the Alcott family and their search for utopia / Richard Francis.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-300-14041-5 (cl: alk. paper) 1. Fruitlands (Harvard, Mass.)History. 2. Alcott, Amos Bronson, 17991888Family. 3. UtopiasMassachusettsHarvardHistory19th century. 4. Communal livingMassachusettsHarvardHistory19th century. 5. Transcendentalism(New England) I. Title.

HX656.F78F73 2010

307.7709744'3dc22

2010019705

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

2014 2013 2012 2011 2010

Contents

List of Illustrations

Plate section

This book is for

Will, Sam, Zac, and Eli

Helen

Jo

my own family

Introduction

A BOUT THIRTY MILES west of Boston there is a pleasant country lane called Prospect Hill Road, alongside which are plump suburban houses with cars in their driveways, basket ball hoops, sheltering bushes and trees. At a certain point on the west side of the road, the land falls away and a huge view opens upthe prospect of Prospect Hill. A driveway snakes down with a scattering of buildings on each side of it. The far one, a deep red clapboard farmhouse, is situated about two-thirds of the way down the slope, tucked into a shallow dell. Beyond it the valley bottoms out into an intervale, as it is technically known, a low-level tract of land by a river, the Nashua River in this case. The view stretches for miles to a couple of far mountains, Wachusett and Monadnock, the intervening land mainly forest with occasional scars from highways, a military base, a prison. But it is still a beautiful place. Standing on the slope of Prospect Hill in the summertime is like being on the shore of a vast green lake.

In 1843 an odd assortment of people assembled at that remote farmhouse (none of the other buildings were there then) to begin an experiment in living. This is the story of one of history's most unsuccessful utopias everbut also one of the most dramatic and significant.

In 1842 Bronson Alcott, a forty-two-year-old out-of-pocket philosopher in a state of deep depression, was funded by his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson to go to England on a morale-boosting trip. Over at Ham, in Surrey, a group of Englishmen had set up a community called Alcott House in his honor.

Both Alcott and his English admirers believed that the Garden of Eden would return if only people avoided meat, cheese, milk, eggs, tea, coffee, and alcohol, preferably living on water and fruit. The English contingent also thought that a new generation of perfected humans could be born if sexual intercourse became entirely devoid of lust and passion. Alcott, however, was happily married and already the father of four daughters (one of whom was the future author of Little Women).

Nevertheless two of the Englishmen, Charles Lane and Henry Wright, decided to go back to America with him to set up a utopian experiment in New England. Lane's ten-year-old son William (product of a previous unhappy marriage) came too. They crammed into the Alcotts' family home in Concord, and then the following summer everyone moved out to the farmhouse off Prospect Hill Road, which they named Fruitlands. Here, with a handful of other followers, they tried to live a self-sufficient life, eating their own produce and wearing homemade linen clothes (one of them believed in wearing nothing at all, in imitation of Adam and Eve).

Soon tension developed on all fronts. Alcott and Lane liked to go on penniless pilgrimages, taking rides across country without paying for them, in an effort to gather new recruitsthey had a tendency to do this just when demanding farm work needed to be done, leaving it to the women and children. The farm chores themselves were made more difficult because the community disapproved of using animals to plow the ground and prohibited the use of manure. There were arguments about money (since the Alcotts did not have any, Lane had to pay for everything). The leaders accused each other of being tyrannical. There was despair about their inability to attract recruits to their austere way of life (the community peaked at thirteen members). One member left because Fruitlands was not spiritual enough; another found the regime too tough (she was thrown out for eating a piece of fish, at least according to one account); anotherthe nudistdecided it was not tough enough and left to be more abstemious elsewhere. Above all, Abigail Alcott realized that Lane's beliefs threatened her marriage and devalued her role as a mother. Soon a battle developed between the two for the possession of her husband. As a savage winter began, she hatched a plan with her brother to bring Fruitlands to an end.

Despite their eccentricity, many of the Fruitlanders' ideas ring bells today. They thought pollution and environmental damage could destroy civilization; they intuited the interconnectedness of all living things, and had an inkling of ecology long before the science had been invented; they were passionately opposed to slavery, and supported women's rights; they believed in civil disobedience, and espoused anarchism. Their experiment is a blend of outmoded and surprisingly modern ways of thinking about the world. Above all it is a very human story of misunderstanding and jealousy, in which a group of idealists end by trying to destroy each other.

Fruitlands was one of a number of utopian communities that were being established in New England at that time. The year previously the Northampton Community for Association and Education had been set up about forty miles from the Fruitlands site on the western edge of Massachusetts; at about the same time the Hopedale Community was established about thirty-five miles to the southwest. These experiments, like Fruitlands itself, advocated abolitionism and temperance but ultimately were not simply a product of particular grievances or issues. They reflected large-scale political and social unease running through both Europe and America, giving rise to the Chartist movement in Britain, for example, and in due course manifesting itself in the repeal of the Corn Laws and, on the European mainland, the revolutions of 1848. The broad impulse behind the American experiments was a reaction to the industrial revolution and the rise of cities, with their consequent social injustice, poverty, and environmental deteriorationdevelopments that had taken place later in the U.S.A. than on the other side of the Atlantic but which were making themselves felt by the 1840s.

Next page

![Alcott - Louisa May Alcott: [a personal biography]](/uploads/posts/book/163779/thumbs/alcott-louisa-may-alcott-a-personal-biography.jpg)