Text copyright 2014 by Miriam Chaikin and Gabriel Lisowski Illustrations and introduction copyright 2014 by Gabriel Lisowski

First Edition

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Art editing: Michal Piekarski

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-62872-318-2

eISBN: 978-1-62872-387-8

Printed in China

For my grandmother, Regina Morgenstern

GL

For my great niece, Josie Alexandra Pearl

MC

Contents

I NTRODUCTION

The cities, towns, and villages of Europe were full of thriving Jewish communities before the advent of Hitler in the 1930s. Most Jews were religious, and most belonged to one of two main schools of Jewish thought, though there were also subgroups and splinters of one group or another.

One school, conservative, believed Jews ought to follow established Jewish law and to worship God with established prayer and by established custom. The other main school, known as Hasidim, which is Yiddish for the Pious, believed God should be worshipped more spontaneously, with joy and with song and dance.

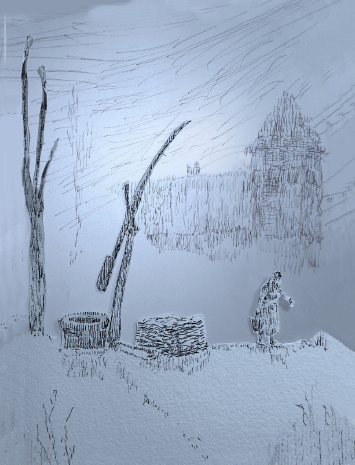

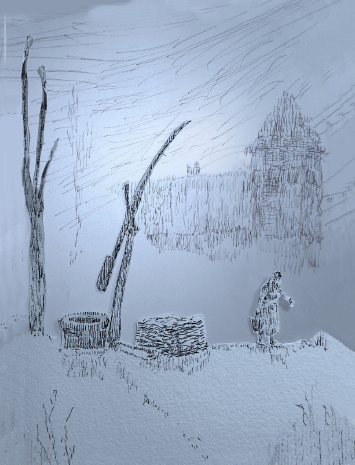

Although large communities of Jews settled in most European cities, Hasidim in Eastern Europe tended to establish themselves in shtetls, Yiddish for little towns. These were self-contained communities, comprised of little wooden houses on unpaved streets, a main synagogue, smaller places of worship, a study house, schools, a court, a cemetery, and a busy marketplace. The head of the shtetl was a charismatic Hasidic rebbe, who was a tzadik or holy Jew, someone whom followers believed to have access to Heaven and whom they accepted as their undisputed leaderlike a little king.

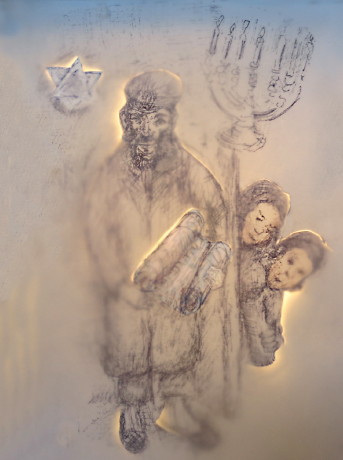

Such a Hasidic master was my maternal great-great-great grandfather, Rabbi Menahem Mendl (17871859) of Kotzk, in Poland. He was famous throughout Europe as a wise and strong-willed spiritual leader and was often called simply the Kotzker or Reb Mendl. People came from everywhere seeking his advice. The advice he gave was not always welcome, though. He was a stern and demanding leader. He minced no words and peppered his speech with insults.

Despite his reputation for rigor, young Jewish scholars came from far and wide to study with him. They had heard that the rebbe disdained the material world, ate little, and cared nothing for refinements of any kind. Even so, it is likely their first impression was one of surprise. Greeting them in the rebbes study was not a neatly dressed man with a combed beard but a tall, thin man with a straggly beard, dressed in rags and wearing house slippers.

His reputation and appearance put no one off. The brightest and most committed remained to become his disciples. His Hasidim, as he called them, revered him and strove to be like him, to the point of dressing in shabby clothes and replacing their shoes with house slippers. Their rebbe did not disappoint them. His scholarship and his reputation as a teacher led to the establishment of his own school of Hasidism. He was one of the great religious leaders who made of Poland a Makom Torah, a place for masters in Torah to study.

Self-examination, truth, and the suppression of ego were central to the Kotzkers teaching. Some Hasidim in other cities and towns were opposed to him. The son of one rabbi, despite his fathers opposition, went to study with the Kotzker. When he returned, his father asked him what he had learned in Kotzk. He said he had learned that it is possible for a person to become higher than an angel, if he wishes it, and that while God created the Beginning, that was only a start and it was up to the rest of us to carry on and build further.

Abraham Joshua Heschel, in his book A Passion for the Truth , finds similarities between the Kotzker and the Danish philosopher Soren Kirkegaard. Both advocated suppressing the ego, the love of self, which they believed led to corruption. To both, the inner life of a person was the main concern. Both sought to strip off the outer garment of belief, the ritual acts, and to strive for truth.

Heschel also compares the rebbe to other Jewish thinkers. Vilna, in Lithuania, was once the center of Jewish learning. Rabbi Elijah, the Gaon (genius) of Vilna, was famous for his work correcting classical texts. While the Gaon was antagonistic to the Kotzkers Hasidic movement, the Kotzker had a high opinion of the Gaon and openly admired him. According to Heschel, The Gaon attained tranquility through Torah study; the Kotzker delved into spheres where spiritual volcanoes erupt. His reward was restlessness and agitation.

The family name of my ancestor Reb Mendl, the Kotzker, was Morgenstern. He established the Kotzker dynasty, as such families were known. His eldest son, Rabbi David Morgenstern, succeeded him as the Kotzker rebbe and was in turn succeeded by other Morgensterns. The family kept the Kotzker rabbinate until the outbreak of World War II, when Hitlers troops invaded Poland and marched across Europe.

Hitler turned the known world upside down in his quest for world domination. His forces rounded up and killed most Jews in work or death camps. Jewish families who managed to escape slaughter were uprooted and scattered to any port or place in the world that would take them in. Members of my immediate family sought refuge in Palestine, a British protectorate. My parents met there and there I was born, in Jerusalem, in 1946.

My father became Polish consul in Palestine until our family returned to Poland in 1948. Ten years later we moved to Vienna, where my father worked for the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Other members of our family remained behind, in Palestine, soon to be called Israel. My grandmother Regina was one of them. She made regular trips to Vienna to see us. As my Hasidic background always interested me, I would question her about Menahem Mendl whenever she came. My questions continued by letter when she returned home.

She told about the Rebbes fame and that he had always liked to be by himself, even when he was young. Later, when he became the Rebbe, he sought opportunities for solitude, to be rid of the mundane distractions that prevented him from basking in Gods light. One day, no one knows why, he isolated himself from the people and remained so for the last twenty years of his life. There are conflicting stories about what drove him to this, but there are no clear answers. An air of mystery remains.