C ONTENTS

In fond memory of my grandparents,

Maud and Leonard Struthers,

who did so much to put the magic

into my childhood Christmases

F OREWORD

Heap on more wood! the wind is chill;

But let it whistle as it will,

Well keep our Christmas merry still.

M ARMION , S IR W ALTER S COTT

EVERYONE HAS THEIR own idea of the perfect merry Christmas. It might be snowy or sunny, steeped in religious meaning or completely secular, an opportunity for total relaxation or some frenetic socialising, a time when old enmities are forgotten or new ones are created. No matter how we choose to spend our Christmas, it gives us another memory that we can look back on in years to come, just as our parents had, and their parents before them, and all the other countless generations going right back to the time when Christmas was first celebrated. And some of our collective memories go back even further than this.

In our artificially illuminated, non-stop world, it is easy to become cut off from the natural course of each season. In mid-December, especially for those of us living in southern Britain, we may not notice that the hours of daylight have shrunk so much that they have reached the darkest point of the winter solstice. Our ancestors, reliant on candles, lanterns and fires, felt gratitude and relief at the knowledge that the days would begin to lengthen again and the suns strength would return. Their lives depended on it, and they celebrated the start of another year with feasting and games long before the birth of Christ. Some of these age-old midwinter festivals still influence the way we celebrate the Twelve Days of Christmas, even if we arent aware of the fact.

The Book of Christmas explores many of these old traditions and activities, from the Roman Saturnalia to medieval mumming, from the antics of the Lord of Misrule to the strictures of the Puritans, from royal excesses to the trials of keeping Christmas when theres a war on. The book tells of angelic visitations, wise men from the east, the star and the stable. There are crackers and trees, candles and gifts, carols and entertainments, feasts and treats, joys and tribulations. And, just like finding those final presents hidden in the toe of a Christmas stocking, there is a lot more besides ancient superstitions, cherished customs, favourite Christmas stories, not to mention folklore, ghosts, sprites and strange legends. A blend of the comforting and the curious.

All the ingredients, in fact, for a delightfully merry Christmas and a happy New Year.

Jane Struthers

East Sussex

E CHOES F ROM THE P AST

The fairest season of the passing year

The merry, merry Christmas time is here.

T HE M ERRY C HRISTMAS T IME , G EORGE A RNOLD

M IDWINTER REVELS

LATE DECEMBER, WHEN the hours of daylight are short and much of nature appears to have gone to sleep, is one of the most important turning points of the year in the northern hemisphere. It is the time of the winter solstice, when the sun appears to be stationary in the sky (and, in the higher latitudes, almost completely disappears) before the days gradually begin to lengthen and the natural world wakes up once more. Its the perfect opportunity to cheer ourselves up with a monumental party and, for those of us with a sense of the spiritual in the middle of the mundane, to honour something greater than ourselves. This celebration has been enjoyed for millennia, in one guise or another.

Saturnalia

Saturnalia

Anyone who complains about the riotous nature of office Christmas parties, or who looks askance at the bottles of alcohol in other peoples supermarket trolleys, might like to reflect that there is nothing new about having a wild time during the winter solstice. The ancient Romans were particularly good at it, as they were with so many other things, and really threw themselves into their own midwinter celebrations, which they called Saturnalia. When they invaded Britain (the first successful invasion was in 54 BC ), they brought their practices with them, and these included Saturnalia.

The festival of Saturnalia was dedicated to the Roman god Saturn, who ruled over agriculture. At the darkest time of the year, when many crops and plants had disappeared underground or died off completely, the Romans wanted to honour their god so he would be pleased with them and bring them good harvests in the coming year. They also had a sense of nostalgia, and Saturnalia was an echo of how they thought life was lived in the time of Saturn.

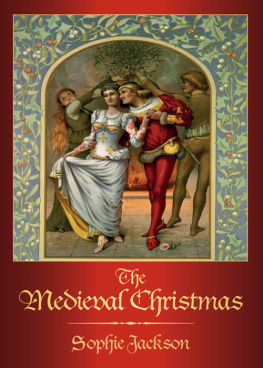

The festival began each year on 17 December, which was a day devoted to religious rites. Everyone went to the temple, where the woollen bands that normally secured the feet of the statue of Saturn were loosened so he could join in the celebrations, and the priests performed sacrifices. After this, there was a public banquet. Everything from schools to businesses and law courts closed down during Saturnalia, and no work was done. Instead, the Romans occupied themselves with the serious business of drinking, eating, dancing, celebrating and cavorting in as uninhibited a fashion as humanly possible. Each social group also elected a man who was the master of ceremonies during Saturnalia, issuing dares and overseeing all the jollity. He was possibly a forerunner of the medieval Lord of Misrule, who was elected to preside over the celebrations at Christmas.

Something else that marked out Saturnalia from the rest of the year was that the social order was turned on its head. Slaves, who were usually respectful and obeyed orders, became the masters. All sorts of activities that were normally forbidden, such as drinking and gambling, were open to them. The masters, whose word was usually law, took the subservient role, serving food to their slaves and carrying out their wishes.

The Romans also exchanged gifts during Saturnalia but often specifically on 23 December, which was known as Sigillaria. Their gifts were more usually tokens of friendship, such as wax or pottery figures, and candles, rather than lavish displays of wealth which would have run contrary to the topsy-turvy nature of the season.

Everyone had so much fun that its no wonder Saturnalia was gradually extended from a single day to a three-day festival, and finally to one that ran until 23 December. Unofficially, it often lasted longer than that, rather in the way that the Christmas holidays are frequently extended today.

The unconquered sun

The unconquered sun

The Romans of the third century celebrated 25 December as Dies natalis Solis Invicti the birthday of the unconquered sun. In 274, the Roman emperor Aurelian declared it to be a major holy day in honour of Sol, the sun god. Opinion is divided on whether this was the start of a new Roman cult or whether it was a revival of an older Syrian cult. Either way, it didnt last long and the figure of Sol disappeared from the face of Roman coinage in 324, during the reign of Constantine, the first Christian Roman emperor.

Saturnalia

Saturnalia