Bibliography

(Books in Japanese are indicated by parenthetical translations of their titles.)

Gakko Kendo Kenkyukai (Society for the Study of School Kendo): Gakko Kendo no Shido (Guide for Teaching Kendo in School), Shubunsha, Tokyo, 1958

Hiyashi, Sansei: Kendo Hoten (Dictionary of Kendo), Mizuhosha, Tokyo , 1953

Inami, Hakusui: Nippon To (The Jaoanese Sword ), Cosmo Publishing Co ., Tokyo 1948

Kaneko, Kinji: Kendo Gaku (Learning Kendo), Shibundo Shoten, Tokyo, 1929

Kashiwai, S.: Kendo no Manahikata (Styles in Learning Kendo), Kinensha, Tokyo, 1956

Mitamura, Kunihiko: Dai Nippon Naginata Kyohan (The Study of Japanese Naginata), Shubundo Shoten, Tokyo, 1938

Nagai, Takaichiro; Otaki, T ado; and Nakano, Yasoji: Sumo, Judo, Kendo (Sumo , Judo, and Kendo), Popurasha, Tokyo, 1960

Nakayama, Hiromichi: Nippon Kendo to Seiyo Kengi (Japanese Kendo and Western Sword Techniques), Shimbi Shoin, Tokyo, 1937

Nawata, Tadao: Kendo no Riron to Jissai (The Theory and Practice of Kendo), Rokumeikan , Tokyo, 1938

Nitobe, Inazo: Bushido: The Soul of Japan, G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1905

Noma, Hisashi: Kendo Tokuhon (Textbook of Kendo). Dai Nippon Yubenkai Kodansha, Tokyo, 1939

Noma, Seiji: Budo Hokan (Handbook of Martial Arts), Dai Nippon Yubenkai Kodansha, Tokyo, 1934

Numata, Yorisuke: Nippon Monshogaku (Study of Japanese Crests), Meiji Shoin, Tokyo, 1926

Sasamori , Junzo: Kendo (Kendo), Obunsha, Tokyo , 1955

Shimizu, Mura: Token Zensho (Study of the Sword), Seikokan, Tokyo, 1926

Shimogawa, C.: Kendo no Hattatsu (The Progress of Kendo), Dai Nippon Butoku-kai Hombu, Kyoto, 1925

Takano, Hiromasa: Shin Kendo (The New Kendo), Meishinsha, Tokyo , 1933

Uragami, Eietsu, and T akeuchi, J.: Kyudo (Archery), Kembunsha, Tokyo, 1928

Warner, Gordon: An Old Sword Flashes in the Dark Shadow, Black Belt Magazine, Vol. 1 , No. 3, Los Angeles, April 1962

:Bushido: Misused and Misunderstood, Kashu Mainichi, Los Angeles, December 1959

:Swords and Armor of Europe and Japan," Black Belt Magazine, Vol. I, No. 2, Los Angeles, January 1962

:Tiger in the Forest," Rafu Shimpo, Los Angeles, January 1961

Wataya, Setsu: Nippon Bugei Shoden (History of Japanese Martial Arts), Jimbutsu Oraisha, Tokyo, 1961

Yamada, A.; Ito, C.; and Motoori, S.: Bujutsu Sosho (The Martial Arts), Hiroya Kokusho Kankokai, Tokyo, 1925

Yamada , Jirokichi: Nippon Kendo Shi (History of Japanese Kendo), Suishinsha, Tokyo, 1922

:Shinshin Shuyo to Kendo Shugi (Physical and Mental Training in Kendo), 2 vols., Suishinsha, Tokyo, 1923

Yumoto, John M.: The Samurai Sword: A Handbook, Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc., Rutland, Vermont, and Tokyo

Tou wa ichiji no haji,

towanu wa matsudai no haji

To ask may be a moment's shame, but not to ask

and remain ignorant is a lifelong shame

1

The Kendo Tradition

Beginnings

It is stated in the opening paragraph of the Japanese government's publication, Its Land, People, and Culture, that the "exact date when the ancestors of the [Yamato] people first settled in the Japanese islands and developed their own culture...remains shrouded in obscurity. Thus it is apparent that little factual knowledge remains of Japan's ancient past.

In the two great anthologies, the Kojiki and the Nihon-shoki, dating from the early 8th century A.D., are brought together a large number of the old Japanese legends, and in the writings of later periods the great wealth of historical landmarks in the life of the Japanese people are ready for the researcher. These old legends make up part of the Japanese national history, and as each nation has its own particular legendary character, each national story is cherished by the population with a personal pride.

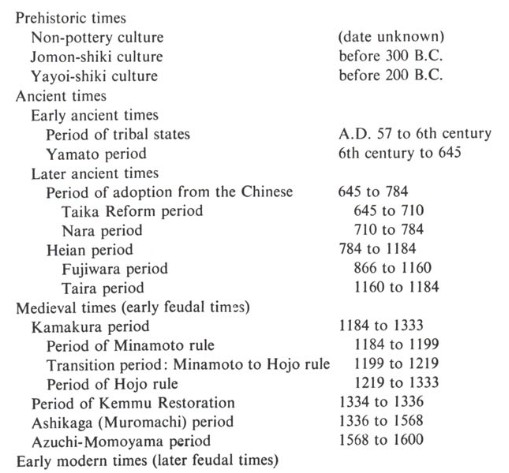

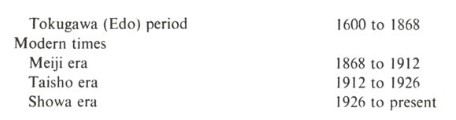

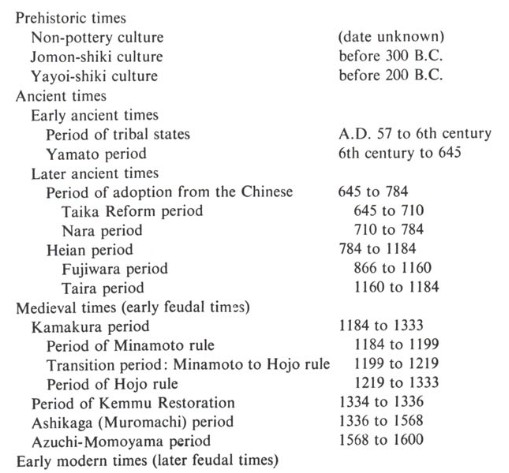

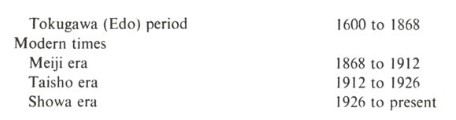

In the study of Japan's historical past, as in the study of any Asian country's past, there will be found specific periods and eras , with the name of each era corresponding to that of the ruling head , but seldom can one find a Christian calendar date to pinpoint the ancient Japanese event in a given Western period of history. For the general orientation of the reader as he follows the history of kendo in this opening chapter, an outline of Japanese historical periods is given below. With this ready reference chart at hand, he can place events in Japanese history correspondently in his own Western historical background.

At this point a note on Japanese personal and era names is pertinent. It must be remembered that in Japan, as in China and Korea, the family name precedes the given name, although in this book, except for the names of feudal daimyo, the Western practice of given name first is followed. It was not until after the Meiji Restoration of 1867 that all Japanese families came to have family names. During the Tokugawa period (1600-1867), just prior to the Meiji Restoration , only the people of the court or the military classes used family names. It should be further pointed out that in Japan even the Imperial Family does not have a name of its own. Therefore only the era name is listed, and when the present emperor came to the throne in 1926 he was known as Michi no Miya Hirohito, although his name will be placed in history as that of Showa (1926- ). For the convenience of the reader, era names appearing in the text are identified in terms of Western-style dates.

Generally a country will have throughout the periods of every century of its own history many chapters written on its particular martial arts. Also, a country will have a national martial art or arts particular to its own culture. The archives of some national libraries hold exciting literature for anyone who cares to hold an armchair conference covering such interesting martial facets of a respective country.

There remains a wealth of such material hidden in the Chinese ideograms of ancient Japanese writings that tell of the struggle for existence by the Japanese bushi and later the knights or samurai. The most important fact about the history of kendo, although this martial art was not called that in the beginning, is that it developed out of Japan's long historical past and is entirely an original art with the Japanese.

It is difficult for even the most able scholars to produce accurately dated historical studies from the three volumes of the Kojiki. The material deals with the period from the mythological ages down to the reign of Suiko Tenno (Empress Suiko, 592-628). The same problem is met in working with the thirty volumes of the Nihon-shoki, completed in 720. These volumes follow the history of Japan from the mythological ages down to the reign of Jito Tenno (Empress Jito, 686-97).

These two documents are generally utilized by Japanese historians to cover the many facets of the ancient past, and it is in them that the first reference is made to Choisai Iizasa in connection with the founding of kenjutsu (ken means sword and jutsu technique or art, and together they mean swordsmanship).

Other historians select Kunimatsu no Mahito as the founder of this ancient art because he was the direct descendant of Amatsu Koyane no Mikoto and was famous as a swordsman. This fable continues with the idea that Kunimatsu no Mahito's style of swordsmanship was the Kashima no tachi or Kashima Shrine style of the sword. The Japanese are aware that Mahito is not a real name, but they have called the style or form of such swordsmanship by this name, and it has continued to be so called through the centuries down to the present.