To Sister Mary Davids parents, Michael and Mary Totah, and her sister, Monelle Totah

Contents

The Abbess and community of St Cecilias Abbey wish to express their gratitude to Sister Elizabeth Burgess for her selection, editing and organisation of Sister Mary Davids writings. We would like to thank, too, all those in the community who shared their private collections of notes from Sister Mary David or who helped to prepare the material for publication, especially Sister Mary Benedict Ryan for her help in reading through and commenting on the proofs, and Mother Eustochium Lee (Prioress), Mother Mary Thomas Brown (Sub-Prioress) and Sister Claire Waddelove for their painstaking work in helping to trace the sources of the many unreferenced texts.

Our thanks also go to Father Abbot Erik Varden for his enthusiasm and support for this project and for his perceptive foreword; to Robin Baird-Smith at Bloomsbury for his valuable guidance and kindly encouragement; and to Jamie Birkett and the editorial team for their expertise and courtesy.

Finally, we would like to extend our thanks to all Sister Mary Davids family, friends and admirers who have long desired the appearing of this book.

In Wagners opera Die Meistersinger , close to five hours of irrepressible singing flow from an encounter that takes place outside Nurembergs Katharinenkirche, where the young Eva Pogner sets eyes on a visiting knight, Walther von Stolzing. She knows at once, with certainty, that he is the man she will marry, he and none other. Magdalena, her chaperone, protests that the knight is quite unknown to her. Eva assures her that, no, he is not: she knew von Stolzing before she ever met him. Their first encounter was marked by recognition, for he came to her, she says, just like David, whose image had long held her in thrall. Ah!, warbles Magdalena, the king with the harp and long beard in the Masters guild sign? To which Eva replies,

No! The one whose pebbles brought Goliath down

sword in belt, sling in hand,

head haloed by blond locks,

the way Master Drer has painted him for us!

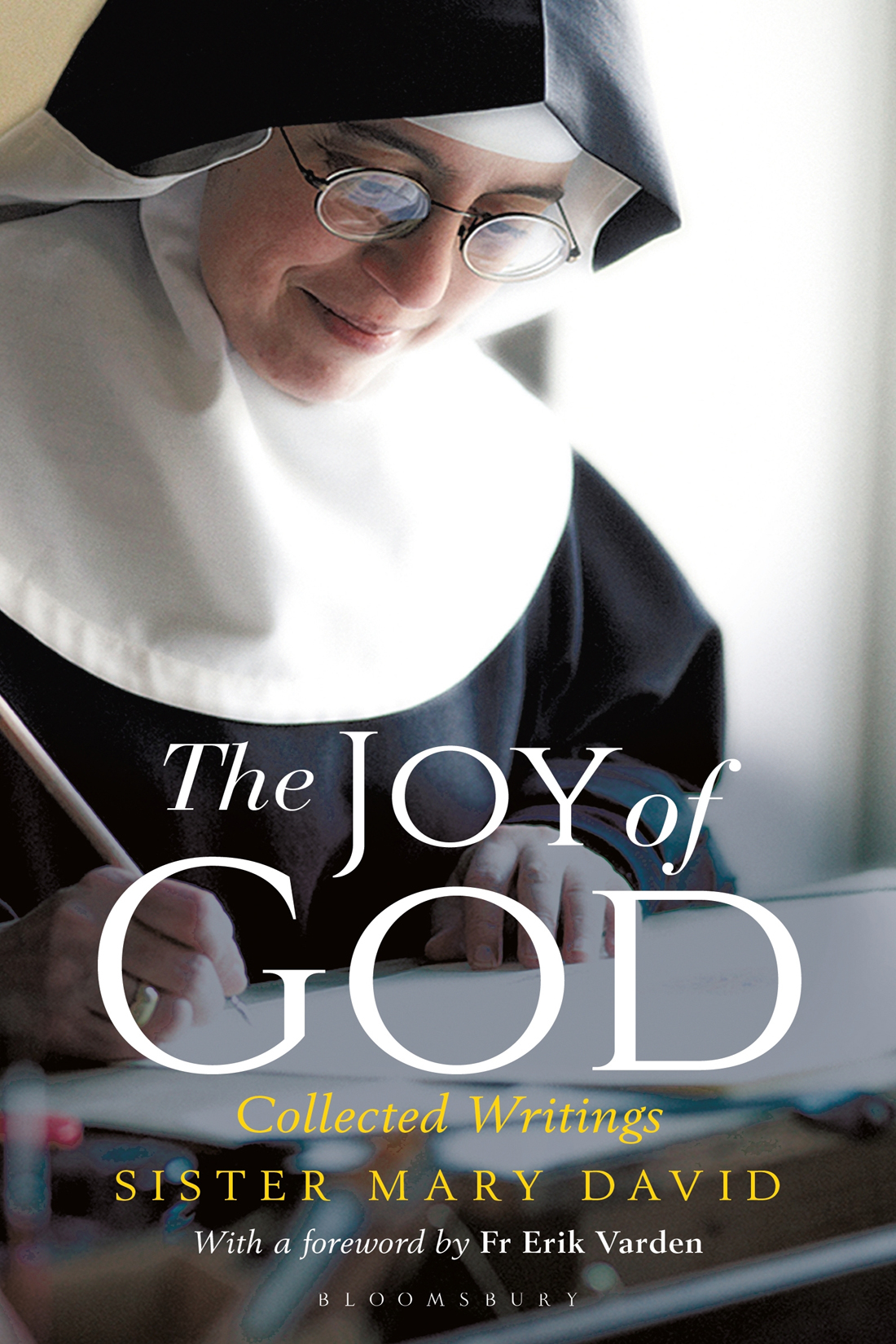

The scene provides an apt vignette with which to introduce the author of this book. After the manner of her Biblical patron, she embodied at once a venerable wisdom and a dash of charismatic pluckiness. No one who knew Sister Mary David Totah (who, like Israels king, was short of stature) will have any trouble imagining her stepping forth to confront some braggart Goliath in the name of goodness and truth, her heart firm in faith, her arsenal simply a handful of stones polished smooth by the waters of the brook from which God himself drank on taking our nature, thereby to lift up both his head and ours for thus the Fathers of the Church would illumine one Biblical passage with another, conflating Davids campaign against the Philistine (1 Samuel 17) with the pathos of the Davidic Psalters most poignantly Messianic Psalm (Psalm 110). It was a kind of reading in which Sister Mary David delighted. Possessed of a sharp, analytical mind, she also had a keen sense of poetry: her doctorate focused on the English symbolists. She was always one to go deeper, to probe further, to extend the horizon, dissatisfied with anything that was less than whole and mindful that the wholeness she sought will tend to exceed what words on their own can express; that it yields its secret most readily through images and signs; that it calls for a response that lets circumscribing reason soar ever higher towards the infinite expanse of love.

*

When at a crucial juncture in sacred history Israels elders decided to abandon the Mosaic institution of Judges and get a king for themselves, they gathered together and came to Samuel at Ramah (1 Samuel 7.4). David, Israels true founding king, later sought asylum in that town when the rages of his star-crossed predecessor Saul contrived his destruction (1 Samuel 19.18). Pundits disagree, as pundits do, on the finer points of Biblical geography, but there is much to indicate that Biblical Ramah overlaps with modern Ramallah, the birthplace of Sister Mary Davids mother and father. Her love of Scripture, its history and sensibility, was not just devoutly acquired; it ran in her blood.

She herself was born in Philadelphia, brought up in Louisiana. Still, her Palestinian origin defined her. It gave a peculiar warmth to her family life. It surrounded her, right into the cloister, with the fragrances and flavours of her fathers exquisite cookery. It gave her a visceral, enlightened understanding of people who found themselves, in one way or another, homeless. It bestowed on her, too, a sense of companionship and fun. Of her relations she wrote:

Naturally talkative and hard-working, they radiate hospitality and warmth; they are a people at home in the world, and one of my familys enduring gifts to me was the appreciation of created values, an awareness that God is glorified in our use and enjoyment of all he has given. There was nothing pinched, arid or abstract about home. I still remember the large family gatherings the platters of stuffed zucchini and vine-leaves, the dancing of the dubka at weddings, the rattle of dice on backgammon boards, and the good-natured shouting and roar of laughter between adults. A cousin once asked his father why he always fought with his relatives. Fight?, he laughed. Thats our way of talking.

Sister Mary David read English Literature at Loyola University, New Orleans, then completed an MA at Virginia. She came to Oxford to do graduate work, among the first intake of women at Christ Church. While covering herself apparently effortlessly with academic glory, she was gregarious, hospitable, and dependable. A contemporary tells of arriving at the college in 1981, feeling overwhelmed, and asking the Head Porter how on earth she was supposed to get started. He simply told her: Youd better go along and meet Miss Totah; thatll be best. A lifelong friendship ensued.

All the while, in Miss Totahs heart of hearts, a deep longing was configuring. Rooted in the Christian faith and practice of her childhood, it revealed itself early as a personal call, a jealous love in the language of Scripture, a love demanding all. Sister Mary David later described to her sisters in the monastery how, as a young woman, she had one day stood in the kitchen back home in Louisiana, among pines and sugar cane, emptying the dishwasher and having this overwhelming and intense experience of the love of God, and a piercing joy. I felt I could have died at that moment and my life would have been complete. From then on God was like a prism through which everything passed, enriching and intensifying life and filling it with wonder.

She first visited St Cecilias Abbey, a Benedictine monastery on the Isle of Wight, in 1984, by then securely launched in an academic career as associate professor of English Literature at the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia. What the monastery embodied perfectly matched her long-entertained, inward desire. Rather like Frulein Pogner before von Stolzing, she took one look at the hitherto unknown and knew : here is my future. The impact of the encounter marked her visibly, to the extent that friends thought she had fallen in love. In May 1985 she entered the monastic enclosure, cheerily proclaiming her intention to remain within it for ever.