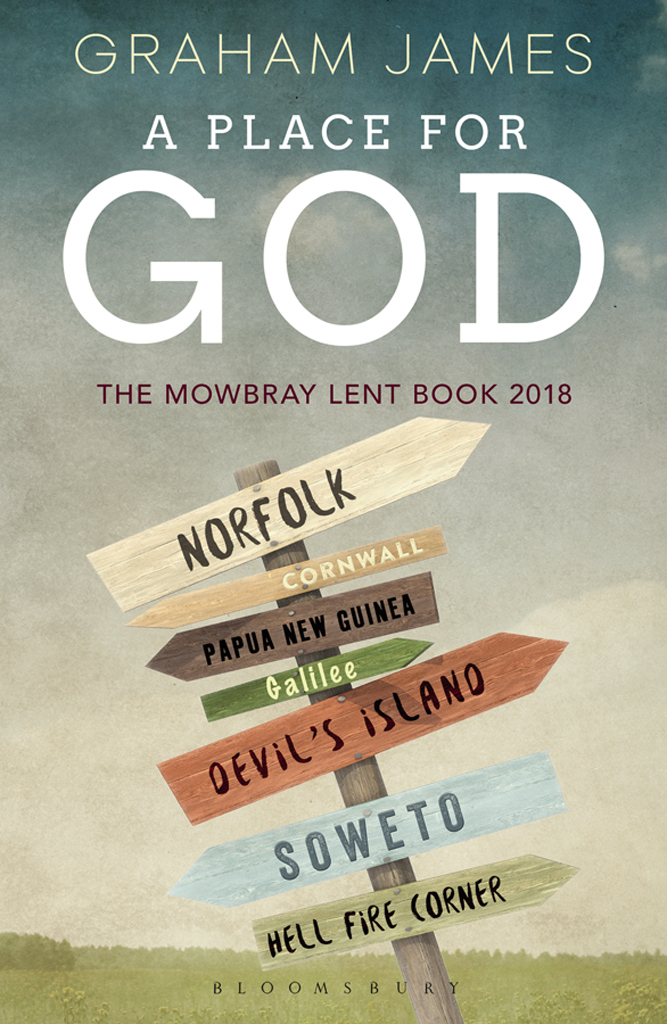

A PLACE FOR GOD

CONTENTS

Whenever I am asked, Where do you come from? I refer invariably to my Cornish ancestry. Yet I have spent only 16 years of my life in my native county. Origins and identity matter to me, as they do to most people. We want to place ourselves in the world. I was tempted to call this book Location, location, vocation because my sense of vocation, both as a Christian and as a priest, has been related more to place than I have sometimes been willing to admit.

Like many clergy I have encountered a deep loyalty to place, which can lead to a parochial outlook that is unwilling to see value in being linked with that parish next door and hesitant about any form of change. Loyalty to place is not always liberating, and yet it is unmistakeable that location matters in the Christian story. Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Nazareth, Capernaum: the places we associate with Jesus are real enough for millions of people today. Whenever I lead a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, I am reminded how frequently locations are identified by name in the Gospels. The Christian faith is not a philosophical abstraction.

All places of encounter with the divine become holy to us. They may not be regarded as sacred by others but there is no limitation on where we may meet God, encounter Jesus Christ or receive a gift of the Holy Spirit. There was nothing originally sacred about the place we know as Bethel. But it became a holy place when Abram built an altar there on his way to Egypt (Genesis 12) and its sacred character was assured when Jacob dreamt there of a ladder stretching from heaven to earth (Genesis 28). Jacob anointed the stone he used as a pillow. The name of Bethel (house of God) became, centuries later, a common designation for nonconformist chapels in England and Wales. Even a tradition with a very limited understanding of sacred space (and sometimes hostility to the very idea) found that Bethel, and other biblical names such as Moriah, Ebenezer and Bethesda, were acceptable dedications for their chapels as places of encounter with the living (and biblical) God.

My earliest years in Cornish nonconformity provided little sense of sacred space beyond the chapels I knew best (two of which are included in a chapter here). I knew them as special places which people dusted and polished, and where they arranged flowers, established childrens corners, sang hymns, said prayers and engaged in a short but very special service after the main one where small cubes of bread and tiny glasses of wine were distributed. (Children were generally excluded from this additional service, which seemed to be only for the very devout.) Above all, these chapels were not accessible shrines. Outside service times, they were resolutely locked.

When, at the age of 11, I began attending Anglican services (not of my own volition but because of a major change in family allegiance), I sensed an immediate difference. The church we attended was a place of daily worship. It was open for people to pray there whenever they wished. A candle flickered before the Blessed Sacrament. A sense of the presence of God, while mysterious and elusive, was much more definitely located. I became aware that sacred space had a character and identity.

It was much later that my understanding of sacred place and space broadened further, but was challenged too. When Jesus encounters the Samaritan woman at the well, he tells her that in future neither on this mountain [Gerizim], nor in Jerusalem, will you worship the Father (John 4.21). This could be interpreted as the clearest command from the Lord himself that the gospel knows of no special sacred places, no hallowed locations, no pilgrimage beyond our journey through this life. There is only the heavenly Jerusalem to which we are called. Meanwhile, we walk as strangers and pilgrims on earth (1 Peter 2.11). We are called to be living stones in a church without physical construction, which is a sign of Gods coming and universal kingdom.

The earth is the Lords, and all that is in it (Psalm 24.1). That conviction is central to the Hebrew Bible, but there is a discernible tension between Gods presence everywhere and the place of his dwelling on earth. The Ark of the Covenant was the manifestation of Gods physical presence in this world. When the Ark travelled, it was constantly accompanied by clouds, a common symbol of Gods presence. When the High Priest entered the sanctuary on the Day of Atonement, he did so under the cover of a cloud of incense, perhaps to prevent anyone from seeing God in all his glory (Leviticus 16.13).

And yet here we encounter a strange phenomenon in the Hebrew Bible. The holiness of the Ark of the Covenant is so great and so concentrated, so saturated with divinity, that its dangerous. When the Philistines capture the Ark, some who merely look at it are killed by its power. In Numbers 4.20 we are told that if those who serve the Tabernacle view the Ark at an improper time they will face immediate death.

This is a warning that God is not to be taken lightly, nor is the divine presence a comfortable one. Even Solomon, upon the completion of what may be the greatest religious building the world has ever known, the temple in Jerusalem, exclaims, The heaven of heavens cannot contain you. How much less this house that I have built! (1 Kings 8.27).

This collection of places where I have encountered God in my life does include religious buildings; considering how much time I have spent within them, it would be surprising if it were otherwise. Even so, many of the settings for an encounter with the divine are not conventionally religious, and the experience was not always immediate. Neither was every encounter initially pleasurable, peaceful or joyful. Places and experiences linger in the memory. A perspective subtly changes; a conviction is reshaped; a sense of calling is confirmed; a glimpse of divine joy comes unbeckoned; a sorrow is redeemed.

Occasionally there is fear. The fear of the Lord may be the beginning of wisdom, but if the living God does not sometimes shame us by the purity of holiness and love then we would hear no call to righteousness and justice at all. Although there are 40 chapters one for each day of Lent for those who wish to read regularly then this is a book for every season of the Churchs year. It isnt conventionally devotional, though there is a suggested (and short) reading from scripture related to each place. A brief prayer concludes each chapter, with two exceptions where the poems quoted are prayers in themselves. The reflections are far from exhaustive, but my hope is that enough will be triggered in the readers own heart, mind and experience to aid further contemplation, prayer and thought. Whats written is an invitation to travel, but the destination is not the sort found in travel brochures; rather, it is in our pilgrimage with and to God revealed in Jesus Christ. Our response to the sort of experiences recorded here is always fitful and incomplete, but I find it hard to understand how so many people can live, as they seem to do, without a place for God.

Matthew 12.4650

Nelson Mandela moved to this address with his first wife Evelyn and their eldest son in 1946. It was a standard house built by tender and commissioned by the Johannesburg City authorities. The South West township of Soweto some 15 kilometres from the city centre was then being developed as a place for black South Africans to live. Nelson Mandela said of 8115 Vila Kazi Street, It was the opposite of grand, but it was the first true home of my own and I was mightily proud. A man is not a man until he has a house of his own.