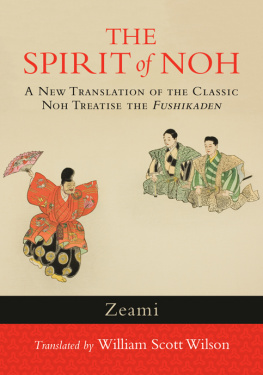

ABOUT THE BOOK

The Japanese dramatic art of Noh has a rich six-hundred-year history and has had a huge influence on Japanese culture and such Western artists as Ezra Pound and The Japanese dramatic art of Noh has long held a fascination for people both in the East and the West. For six hundred years it has had a huge influence on Japanese cultureand has inspired such Western artists as Ezra Pound and William Butler Yeats. Here is a translation of the Fushikaden, a seminal treatise on Noh by the fifteenth-century actor and playwright Zeami (13631443), the most celebrated figure in the arts history. His writings on Noh were originally secret teachings that were later coveted among the highest ranks of the samurai class and first became available to the general public only in the twentieth century. The Fushikaden is the best known of Zeamis writings on Noh and it provides practical instruction for actors, gives valuable teachings on the aesthetics and spiritual culture of Japan, and offers a philosophical outlook on life.

Along with the Fushikaden, translator William Scott Wilson includes a comprehensive introduction describing the intriguing history behind this enigmatic and influential art form, and also a new translation of one of Zeamis most moving plays, Atsumori.

ZEAMI (13631443) is considered the most important playwright, actor, and theorist in the history of Japanese Noh theatre. Along with his father, Kanami, he revolutionized Noh, turning it into a nuanced art form that greatly influenced many aspects of Japanese art and culture. He was a prolific writer, and his plays make up a significant part of the Noh repertoire.

Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

THE SPIRIT OF NOH

A New Translation of the Classic Noh Treatise the Fushikaden

Zeami

TRANSLATED BY

William Scott Wilson

SHAMBHALA

Boston & London

2013

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

2006 by William Scott Wilson

This book was previously published under the title The Flowering Spirit: Classic Teachings on the Art of N.

Cover art: Tsukioka Gyokusei, Japanese, 19082009. Fukunokami, from the series Fifty Kyogen Plays (Kyogen gojuban), published 1927. Color woodblock print, bequest of Henry C. Schwab, 1943.832.31, The Art Institute of Chicago. Photography The Art Institute of Chicago.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zeami, 13631443.

[Fushi kaden. English]

The spirit of Noh: a new translation of the classic Noh treatise the/Zeami; translated by William Scott Wilson.

pages cm

Previously published: Tokyo: Kodansha, 2006.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2898-8

ISBN 978-1-59030-994-0 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. No. I. Wilson, William Scott, 1944 II. Title.

PN2924.5.N6Z4343313 2013

792.0952dc23

2012042961

This translation is dedicated to

the memory of Dana Todd Richardson.

CONTENTS

PUBLISHERS NOTE

This book contains Chinese and Japanese characters. If you encounter difficulty displaying these characters, please set your e-reader to publisher defaults (if available) or to an alternate font.

I saw my first Noh play about thirty-five years ago on the grounds of the Atsuta Shrine in Nagoya, Japan. The memory of that experience, even today, is still vivid: the almost unbelievably slow movements of the demon-masked shite, or main actor; the beating of various small drums in unfamiliar rhythms that seemed to evoke dim memories or dreams; the flute emitting sounds more like squeaks than melodies; and the intermittent birdlike cries of the musicians. Plays or operas I had seen growing up in America had always taken me to a different time and place, but they were times and places in this world. The Noh play was very different in that regard.

One other thing that impressed me that day was that almost everyone in the audience of perhaps sixty had copies of the libretto, and was reading along with the performance. This was also quite different from my experience of drama in my own country. What I didnt know at the time was that the language of the play was some six hundred years old, and even if one was conversant with that ancient form, the droning delivery of the actors and the shites mask obscured the words even further.

Years later, I had the good fortune to take a graduate course in Noh as literature at the University of Washington under the tutelage of Dr. Richard N. McKinnon. Dr. McKinnon had professional connections with a troupe in Japan, and during our class he would periodically stop our reading of the plays and chant the section himself to give us a better understanding of the atmosphere of the material. It was a late-afternoon class and, as dim orange sunlight filtered through the high second-floor windows, I can remember the hair standing up on the backs of our necks. As he chanted, Dr. McKinnon seemed to be almost possessed by someone or something else, but then he would suddenly stop and, with a kind smile, ask us to continue with the reading.

The fundamental handbook translated here, the Fushikaden, has been a sort of bible for Noh actors ever since Zeami Motokiyo perfected the genre and wrote out the notes for it, between 1400 and 1418. It was at first a secret document, so to possess a copy was considered great good fortunenot only by professional actors, but also by the upper echelons of the warrior class. High-ranking samurai practiced the chants, dances, and music of Noh with great enthusiasm, linking this in part to their attainment of high culture, in part to their study of Zen Buddhism, and sometimes even to the art of swordsmanship. The Fushikaden is, even today, read widely enough to require frequent publications and translations into modern Japanese, and offers proof in one slender volume to the oft-quoted statement that The study of the Noh play is really the study of Japanese culture generally.

In this regard, a word should be said about the text. It is well known that Zeamis style and vocabulary can be somewhat vague, and translatorsrendering the Fushikaden into both English and modern Japaneseare not in agreement as to the meanings of certain terms. To make matters more complicated, Zeami seems to have had a rather fluid sense of definition, so that a word might mean one thing in one section of the book, and something slightly different in another. I have dealt with this problem in part by leaving a few words in the original Japanese and adding a glossary, so that the reader will have a sense of the breadth of a single word; in other cases, I have simply used a more appropriate English term. I have tried to stay as close as possible to the original to convey the range of expression and individual quirks in Zeamis writing. As in all texts of this age, a number of slightly differing versions exist. While relying heavily on the notes and annotations of Nose Asajis Zeami juroku bushu hyoshaku, I have based the translation on the Fushikaden edited by Nogami Toyoichiro and Nishio Minoru, and published by Iwanami Shoten. The

Next page