Arts and Traditions of the Table: Perspectives on Culinary History

Arts and Traditions of the Table: Perspectives on Culinary HistoryAlbert Sonnenfeld, Series Editor

Salt: Grain of Life, Pierre Laszlo, translated by Mary Beth Mader

Culture of the Fork, Giovanni Rebora, translated by Albert Sonnenfeld

French Gastronomy: The History and Geography of a Passion, Jean-Robert Pitte, translated by Jody Gladding

Pasta: The Story of a Universal Food, Silvano Serventi and Franoise Sabban, translated by Antony Shugar

Slow Food: The Case for Taste, Carlo Petrini, translated by William McCuaig

Italian Cuisine: A Cultural History, Alberto Capatti and Massimo Montanari, translated by ine OHealy

British Food: An Extraordinary Thousand Years of History, Colin Spencer

A Revolution in Eating: How the Quest for Food Shaped America, James E. McWilliams

Sacred Cow, Mad Cow: A History of Food Fears, Madeleine Ferrires, translated by Jody Gladding

Molecular Gastronomy: Exploring the Science of Flavor, Herv This, translated by M. B. DeBevoise

Food Is Culture, Massimo Montanari, translated by Albert Sonnenfeld

Kitchen Mysteries: Revealing the Science of Cooking, Herv This, translated by Jody Gladding

Hog and Hominy: Soul Food from Africa to America, Frederick Douglass Opie

Gastropolis: Food and New York City, edited by Annie Hauck-Lawson andJonathan Deutsch

Eating History: Thirty Turning Points in the Making of American Cuisine, Andrew F. Smith

The Science of the Oven, Herv This, translated by Jody Gladding

Columbia University Press  NEW YORK

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York. Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2010 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-52550-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gentilcore, David.

Pomodoro! : a history of the tomato in Italy / David Gentilcore.

p. cm. (Arts and traditions of the table : perspectives on culinary history)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-15206-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-52550-3 (e-book)

1. Cookery (Tomatoes). 2. TomatoesItaly. 3. TomatoesHistory. I. Title.

TX803.T6G46 2010

641.6'56420945dc22 2009052786

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

For Mum, who still bottles her own

Contents

Italy is Europes premier tomato nation. Its total production of fresh and processed tomatoes is more than that of all the continents major tomato-growing countries put together. In Italy today, something like 32,000 acresare dedicated to tomato cultivation, producing around 6.6 million tons of tomatoes for the food industry. The market is worth an astonishing $2.2 billion. Tomatoes are consumed both fresh (raw and cooked) and preserved (in cans, jars, and tubes), and their use in sauces with pasta has become a stereotypical element of Italian cookery, even for Italians. In Italy and beyond, the health benefits of tomatoes are praised as a basic element in the Mediterranean diet. Lycopene, an antioxidant that tomatoes contain, is known to lower the risk of heart disease, cancer, and prematureaging. Never has the tomato enjoyed such favor as it does today.

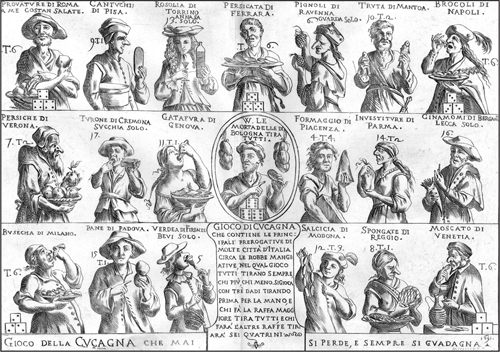

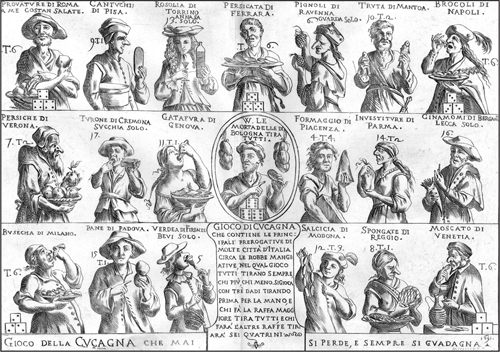

It took a very long time for this to happen, three centuries in fact. The initial reception of tomatoes was hostile, as sixteenth-century physicianswere unanimous in regarding this Mexican native as poisonous, the generator of melancholic humors. And if the tomato is stereotypical of Italy now, correctly or not, it certainly was not in previous centuries. But there were other stereotypes. In a 1615 letter to the French queen Maria de Medici from Mantua, the comic actor and playwright Tristano Martinelli wrote that he was as eager to visit her in Paris as a Florentine is to eat little fish from the Arno, a Venetian to eat oysters, a Neapolitan broccoli, a Sicilian macaroni, a Genoese gatafura [a cheese-based pie], aCremonese beans, a Milanese tripe. Three-quarters of a century later, the same regional stereotypes, plus a few more, were represented in print by Giuseppe Maria Mitelli (). Not a tomato in sight!

More than three hundred years separate the tomatos first arrival in Italy in the mid-sixteenth century from its consumption and cultivation on a large scale. Even today, there are areas of Italy where relatively few tomatoes are consumed and cultivated.

The combination of pasta with tomato sauce, pasta al pomodoro, is so widely consumed that it is hard to imagine that it dates back to only thelate nineteenth century, by coincidence around the same time that millionsof Italians started crossing the ocean to the New World, where the tomato originated. Without this amazing, fortuitous creation, the world would be a much less enjoyable place. Recalling a meal with the dramatist and all-round Fascist celebrity Gabriele DAnnunzio in the 1930s, the poet Umberto Saba recalled the revelation when he was first offered a plate of pasta with tomato sauce. DAnnunzio may have been a disappointment, Saba wrote, but the pasta was not; it was a crimson marvel(purpurea meraviglia).

Giuseppe Maria Mitellis print depicts early Italian food stereotypes in the form of a board game, Gioco della cuccagna che mai si perde e sempre si guadagna (1691). ( Trustees of the British Museum)

How the tomato came to dominate Italian cookery after such inauspicious beginnings is the theme of this book. We shall look at why tomatoes took so long to be adopted and where in Italy they eventually became popular. We shall consider the international nature of the Italian tomato, since it traveled across the Atlanticseveral timesand beyond. We will look at the presence of the tomato in elite and peasant culture, in family cookbooks and kitchen account books, in travelers reports, and in Italian art, literature, and film. The story will take us from the tomato as a botanical curiosity (in the sixteenth century) to changingattitudes toward vegetables (in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries);from the tomatos gradual adoption as a condiment (in the eighteenth century) to its widespread cultivation for canning and concentrate and its happy marriage with factory-produced pasta (both in the late nineteenth century); and from its adoption as a national symbol, both by Italian emigrants abroad and during the Fascist period, to its spread throughout the peninsula (in the twentieth century).

But this is more than just a history of the tomato. From the start, the tomato was closely linked to food ideas and habits as well as with otherfoodstuffs, with pizza and pasta being only the most obvious. Finally, the tomatos uses were continually subject to change, from production to exchange, distribution, and consumption. For all these reasons, the tomato is an ideal basis for examining the prevailing values, beliefs, conditions, and structures in the society of which it was a part and how they changed over several centuries.

NEW YORK

NEW YORK