Massimo Montanari is a Professor of Medieval History at the University of Bologna, where he also teaches History of Nutrition. One of the founders and editor of the Food & History journal, he is among Europes foremost scholars of the evolution of agriculture, landscape, food, and nutrition.

Gregory Contis translations for Europa Editions include Alessandro Barberos The Eyes of Venice, and Alberto Angelas A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome, which was voted a Best Book of the Year by the Kansas City Star and became an Indie Bound bestseller.

A SHORT HISTORY

OF SPAGHETTI

WITH TOMATO SAUCE

Birth, what does that mean?

Dear Doctor, what matters is growth,

And, modestly, that little lady there has had some growth...

Whoa!

Tot in Paris, 1958

W ORDS: H ANDLE WITH C ARE

T he Idol of Origins. Thats what Marc Bloch, the greatest European historian of the XX century, called it. Searching the past for what paved the way for the present, according to Bloch, is an obsession typical of those who concern themselves with history. It also dominates the collective imagination. Nothing wrong with that, on the face of it. It all depends on what you mean by origins. Simply the beginnings? In that case, the concept is fairly clear. Or does it also mean causes? In that case, what were looking at is a historical determinism that is both nave and unsustainable, as well as contradicted by experience. Given a point of departure X, there is no single destination Y but rather a multiplicity of possible directions, defined by circumstances, the interaction of various forces, chance, and the unforeseeable.

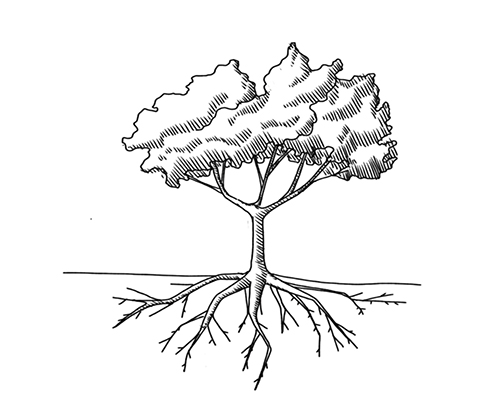

The problem is that these two interpretations are often combined in a logical misstep. In popular usage, an origin is a beginning which explains. Worse still, a beginning which is a complete explanation. Thats where the ambiguity lies, the danger. Confusing lineage with explanation. Because an acorn is not an oak tree.

Blochs metaphor is brilliant. Great oaks from little acorns grow. But only if they meet favorable conditions of soil and climate, conditions which are entirely beyond the scope of embryology. And this is what really interests the historian, the analysis of the environmental conditions, the economic, social, and cultural humus that allow the acorn to become an oak tree. From that perspective, are the origins really all that important?

Actually, origins dont explain anything, because a seed is necessary to give life to a plant, but not sufficient to generate a root, and, from it, a plant. Thats what origins really are, not a cause but simply a seed that can turn into a plant, providing it encounters a favorable environment. The key word here is encounter. The more numerous and more interesting the encounters, the richer the result, the stronger and more robust the plant. In this way, it will have constructed its own identity, which, like all products of history, is alive and changeable. Alive because it is changeablemovement is the cause of all life is the celebrated phrase of Leonardo Da Vinci. With regard to the roots that have made this identity possible, throwing oneself into the search for them is an experience that can turn out to be more adventurous than expected, leading us to visit places, societies, and cultures that are not necessarily our own.

Roots and identity are perilous words, to be handled with care. Too often, they are misunderstood and confused, when it is important to distinguish them. Roots inhabit the past. On the time line, if we want to recount the birth, growth, and development of anything, they are at the beginning, and they expand in space to take nourishment from every reachable source (the botanical metaphor, if it is to be useful, must be squeezed to its full potential). At the other end of the time line are identities, which, instead, inhabit the presenta mobile present, always intent on projecting itself into the future all the while becoming itself the past. At any point on the chronological line, identities are a destination: characterized by well-defined mental and material spaces, but always unstable and changeable, as is proper to everything that lives.

Losing sight of the vitality of identities means denying oneself a truly historical outlook on them and the roots from which they spring, or their origins. It means thinking of them as immutable with respect to the future, devoting oneself not to keeping them alivewith the opportune adaptationsbut to freezing them, codifying them, confining them to museums. It means thinking of them as immutable with respect to the pasta past that thus becomes pure legend and a colossal mystification. It is the idol of origins that crops up again, against all evidence, against all logic. And this justifies the radical choices of those who do not limit themselves to recommending caution in the use of these concepts and terminology but oppose them to the point of eliminating them from the vocabulary and from the collective imagination. Against Roots is the title of a book by Maurizio Bettini, to cite just two exemplary cases. This little essay could have been called Against Origins. But the historian holds on to the illusion that the simple recounting of the facts can help to shed light on the meaning of words and things. Especially when the things are aspects of the life that we confront on a daily basis. For example, food, food products, and cooking recipes.

Is it possible to sit down to a plate of spaghetti with tomato sauce and reflect on the meaning of roots, identities, and origins? That is what I have tried to do in these pages.

R ECIPES AND P RODUCTS,

O R R ATHER, T IME AND S PACE

W hen we eat, and when we talk about food, misunderstandings and mystifications are part of the agenda, and they have a strong emotional impact. Indeed, everything that regards food and the dining table evokes profound values and sensations connected to personal identity. As always, material reality (our ways of living) and mental reality (our ways of thinking) interact and, in this case as in othersperhaps more than in othersour imagination is conditioned by prejudices, clichs, myths, fantasies, and idols. The idol of origins is the most powerful and it forces itself on the individual and collective consciousness, in terms of both time and space.

Time is the dimension of recipes, whose origins we often try to find by searching for some specific episode, the exact moment when someone had the idea to make it for the very first time. An age-old obsession. Catalogue of the inventors of things that we eat and drink is the semi-serious title of a curious work by the Milanese humanist Ortensio Lando, published in 1548. Combing through ancient literature and adding a lot from his own imagination, he delights in recounting who was the first to eat rosemary and elderberry pancakes, or to fry bread in butter, or to eat a soup of barley and ground oats.

In this case, the myth of the origins rises to the level of methodalbeit in a humorous waybut we all know stories and anecdotes that ascribe this or that recipe to improbable historical figures: the chef, the lord, the monk are the most frequent suspects, but there is no lack of shepherds and farmers in an explosive mix of lucky coincidences, and inventions compelled by hunger, chance, and happenstance. The important thing is to establish an origin, which calms and reassures. No matter that, in this way,