Medieval Tastes

ARTS AND TRADITIONS OF THE TABLE

ARTS AND TRADITIONS OF THE TABLE: PERSPECTIVES ON CULINARY HISTORY

Albert Sonnenfeld, Series Editor

For the list of titles in this series, see

Medieval Tastes

Food, Cooking, and the Table

Massimo Montanari

TRANSLATED BY BETH ARCHER BROMBERT

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2012 Gius, Laterza & Figli. All rights reserved. Published by arrangement with Marco Vigevani Agenzia Letteraria

Translation copyright 2015 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53908-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Montanari, Massimo, 1949- [Gusti del Medioevo. English] Medieval Tastes : food, cooking, and the table / Massimo Montanari; translated by Beth Archer Brombert.

pages cm

Translation of: Gusti del Medioevo. Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16786-4 (cloth : alk. paper)978-0-231-53908-1 (ebook)

1. FoodEuropeHistoryTo 1500.

2. Food habitsEuropeHistoryTo 1500.

3. Cooking, Medieval.

I. Title.

TX351.M6613 2015

394.1'20940902dc23

2014023679

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

COVER ART: Bibliothque Nationale, Paris, France/Bridgeman Images

COVER DESIGN: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Contents

WHEN IT COMES to food and cooking, the Middle Ages often take the starring role. This is not only because medievalists, like all historians, devote much attention nowadays to this long neglected subject of history but also because marketing strategies for food production and catering were born in the Middle Ages. In truth, Middle Ages in most cases is no more than a generic term used to evoke an equally generic image. But that term and that image are evidently considered useful for selling and making more appealing commercial offerings. The term medieval attributes an added value to products and services. History is brought into play as the locus of birth and origin.

This is a concern typical of our era: to authenticate the present by recalling the past, to legitimize what we are making now by saying that it used to be made long ago. The expression long ago, historically meaningless, indicates something of a more genuine nature than does a time past; long ago is an indistinct, mythical time when things are presumed to have come into being. Then they came down to us, after a historical journey, which is, in reality, without history because nothing happens then. The tradition invoked is not the fruit of events, experiences, encounters, changes, inventions, and compromiseshistory, in a wordbut is static and immobile. It is the idol of origins, about which Marc Bloch has written, which leads us to explain the most recent by means of the most remote.

If we look at European labelsDOP, IGP, STGproclaiming the denomination of protected origins, protected geographic origins, and guaranteed traditional specialties, we are amazed by the vagueness of historical documentation, which, after all, is the requisite foundation for authenticating and registering a product. References, when there are any, are second- and thirdhand. History is reduced to anecdotal snippets of little interest other than fulfilling a legislative requirement to provide the pedigree of the product, placing it in a context of consolidated tradition. That tradition may even be extremely recent. At present, it takes only twenty-five years for a product to acquire recognition as typical or traditional. With regard to image, however, ancient looks better than modern. To claim medieval or, even better, Roman origin is a way of enhancing the nobility of the product. The older the history and the more remote the origin, the more the product will seem worthy of being safeguarded.

The basic assumption is to think of continuity as a seal of guarantee. That things are subject to continuous modifications, that the flavors of foods and the tastes of people change with time, that the social and cultural contexts determine constantly changing forms of usage, that the same objects do not always correspond to the same namesall this, which is obvious to the historian, is of no interest to the general public. They would rather believe that tradition all by itself is a guarantee of quality, and believing that it has always been made this way, generation after generation, is enough for total assurance.

The term Middle Ages used in the marketing of food means tradition, origins, antiquity; it means once upon a time.

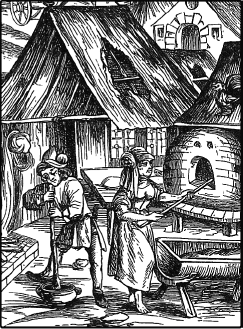

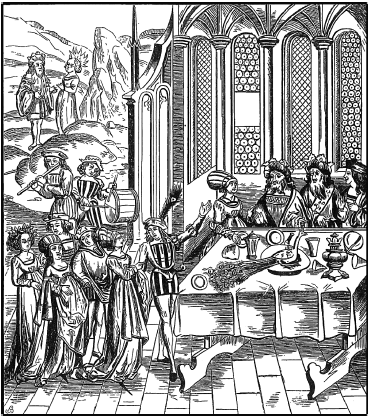

By analyzing this imaginary construct, the language that produces it, and the rhetoric that sustains it, one thing becomes apparent. In the promotion of food products, no discussion under the aura of the Middle Ages is negative because of the value automatically endowed by the antiquity of tradition, whoever its guarantors: peasants weighted with experience and inventiveness, landowners in search of new pleasures, and cooks able to benefit from available resources (or from their occasional scarcity, for which they made up with ingenious creativity), as well as clever artisans and shopkeepers and, finally, monks, the absolute warranty of gastronomic know-how.

We should pause for a moment to consider the invariably positive nature of medieval images related to food products, for this is a culturally anomalous factor, contradictory to the ambiguity always associated with the idea of the Middle Ages in the contemporary imagination. Such an idea is twofold: the Middle Ages are a period of glorious adventures, of amorous damsels and brave knights, of deep and noble sentiments; but they are also a time of obscurity and fear, superstition, violence, and barbarism. The two images, both of them uncertain, are not gratuitous inventions of popular fantasy but arose out of centuries of historiographic inventions, initiated by the humanists of the Renaissance, who characterized the Middle Ages as void of civilization. What else can the term medieval suggest, linked by humanists to that millennium, if not the notion of a middle period, a lengthy pause while awaiting the return of civilization after a temporary eclipse? The obscure and irrational image of the Middle Ages was consolidated during the Protestant Reformation, which attacked the church of Rome as the depository of medieval corruption and superstition. To this was later added the Enlightenment polemic against feudal privileges and abusive powers incorrectly attributed to the Middle Ages (and, on the contrary, entirely modern).