For Robert J. Powers

A friend, gentleman, and entrepreneur who embodied the values expressed in this work. R.I.P.

A Note on the Use of the King James Version of the Bible

G iven what some might perceive to be the oddity of a Catholic priest electing to use the Authorized or King James Version of the Bible in the course of this study of the parables, I thought it prudent to offer the reasons for my choice.

The reader will immediately see from the various sources I have employed throughout the text that I have endeavored to make this book widely accessible to a diverse and interfaith audience. I simply want to reach as many people, from all religious approaches, as possible. Yet, that is not the reason I chose to use the KJV.

Despite being raised in an Italian-American Catholic household, my upbringing in Brooklyn, New York, afforded me diverse experiences and friendships. In my teens I went to lots of Protestant churches with my friends. It was there, especially at Black Pentecostal churches, that I first learned to love Black gospel music and the cadence of the KJV Bible.

I grant that the KJV is not the easiest translation for many people to follow, in the same way that some people find Shakespeare difficult. It is not even, given modern scholarship, the most accurate and useful translation for serious study. But its capacity to evoke devotion and reverence and the use of what some have called Biblical English in the KJV, helps to capture the style of the original Hebrew and Greek, and is especially suited for the forceful and majestic dialogue of the parables and the lessons they contain.

I NTRODUCTION The Enduring Power of the Parables

L ibraries are filled with books on the parables of Christ, and rightly so. Here we have stories full of surprising details and challenging conclusions that offer moral direction of great potency. They cause us to pause and think. There is no doubt that the parables constitute the heart of Jesus preaching, wrote Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI. While civilizations have come and gone, these stories continue to teach us anew with their freshness and their humanity.

Many of their lessons are counterintuitive. They are more difficult to understand than we might initially expect. And yet we tend to remember them. Many of them long ago entered into the popular imagination and have stayed there, even in highly secularized times, detached from their contexts. While they are stories kindred with fables, legends, folklores, allegories, and myths; parablesand the parables of Jesus in particularare something more because they so readily prompt us to examine our hearts and think through eternal matters from the perspective of the whole of Christs teaching and person, by way of practical examples from our daily experience.

The Latin word parabola is derived from the Greek parabol, meaning to throw, or put by the side of, or place side by side. The word was used by Plato and Socrates to mean a comparative story, a fictitious analogy designed to reveal a deeper truth.

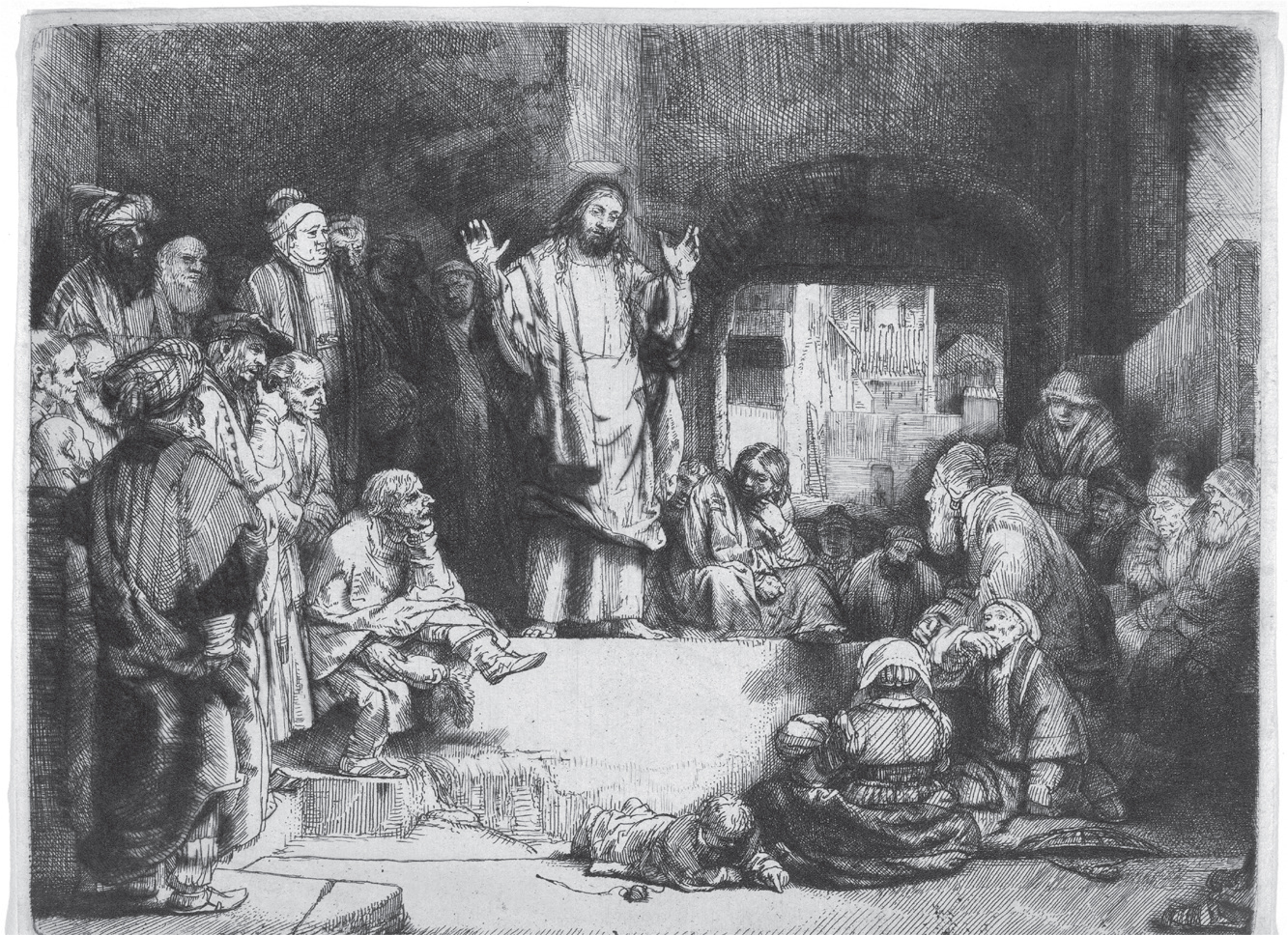

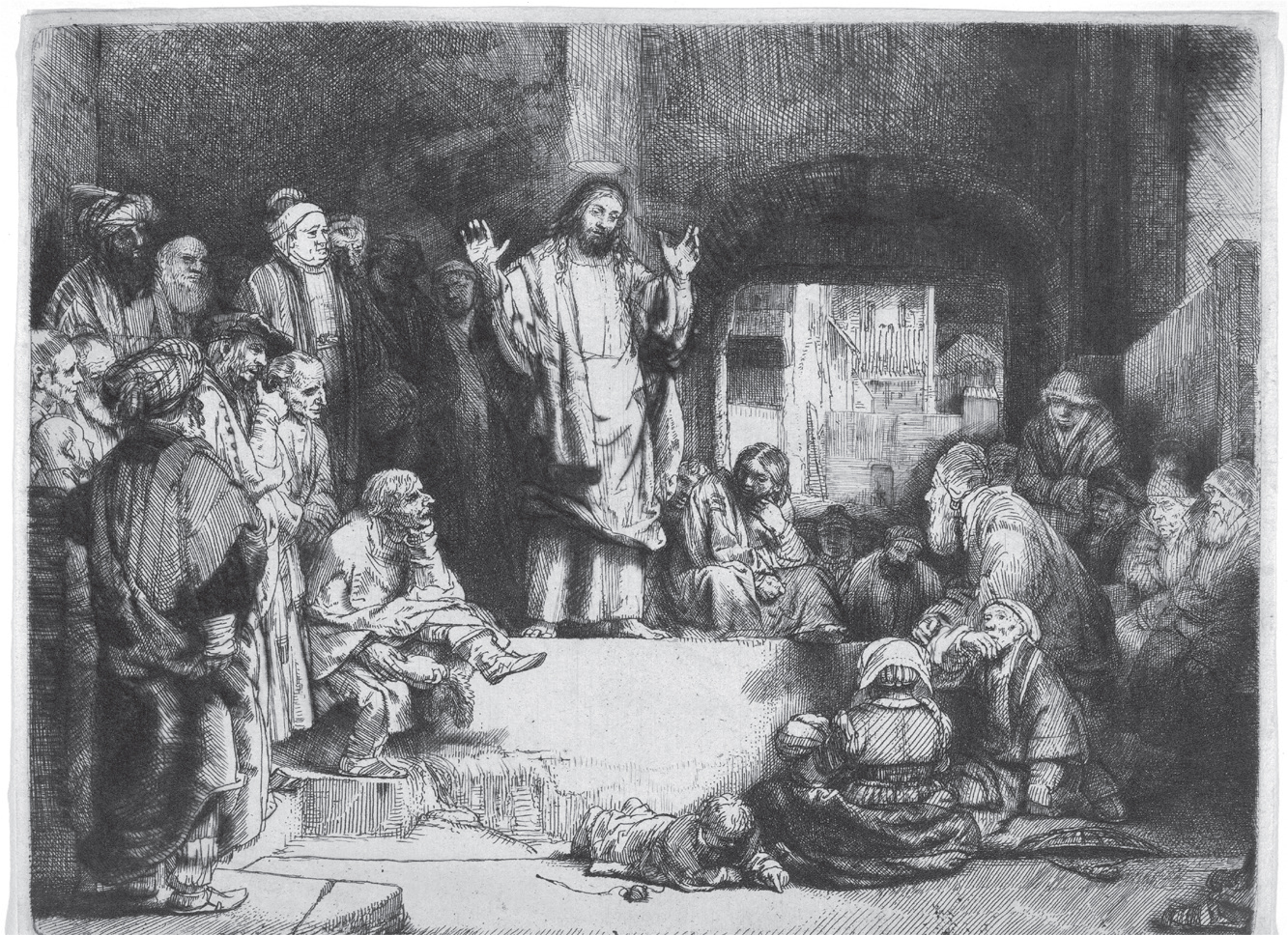

Christ Preaching by Rembrandt . Library of Congress

Parables have been used throughout history as rhetorical or teaching devices. But the parables of Jesus are not merely didactic; they convey transcendent meaning not to be found on their surface, and the implications of His parables demand our engagement and our choice.

There was a political backdrop to the parabolic approach to teaching. Jesus public ministry took place amidst an atmosphere of political and religious danger. The Roman state, like all states, wanted no competitors and was quick to judge anyone it so regarded as an enemy. Jesus fellow Jews awaited the Messiah, but their leaders had every interest in prolonging the wait as long as possible.

So how could Jesus convey his teachings in a way that would be understood with precision by those open to his message, and at the same time not alarm those without ears to hear, thus inciting controversy that would distract from his principal focus? His parables were part of the answer. Therefore speak I to them in parables, he said, because they seeing see not; and hearing they hear not, neither do they understand (Matthew 13:13).

Jesus wants to show how something they have hitherto not perceived can be glimpsed via a reality that does fall within their range of experience, explains Benedict XVI. By means of [a] parable he brings something distant within their reach so that, using the parable as a bridge, they can arrive at what was previously unknown.

The parable must be distinguished from pure allegory. Parables deal with a piece of real life, something that might very well have happened, whereas allegory is more likely to deal with pure fantasy in order to illustrate a metaphorical meaning. Parables teach on two levels: the real-life message and the theological analog. In order to comprehend the fullness of the message, both must be understood.

Leopold Fonck, whose classic work on Jesus parables is noteworthy, argues that a parable in the Christian sense has four elements: 1) the discourse has an internal independence and completeness, so that it makes sense on its own, 2) it must point to a supernatural truth, 3) this truth must be clothed in figurative language, and 4) the two must be compared.

One can hear the parables as a follower who believes Jesus to be the Son of God. Or one can hear them as a person who regards the teacher to be a great moral figure. One may even hear the parables for their literary or rhetorical force alone. And one can hear the story in its most plain and mundane meaning and still gain insight. Some do not require any explanation. Yet deep reflection is required of them all.

Parables are most often discussed in terms of their higher meaning, and surely that is the primary idea and goal. To hear and repeat a wonderful story while missing its larger purpose and lesson defeats the point of the parable. Yet it remains true that the parables of Jesus are classic stories in and of themselves. The moral and spiritual significance of their lessons can be deepened and more clearly elucidated if we develop a richer understanding of the circumstances, logic, presuppositions, and meaning of the stories themselves.

The enduring power of the stories themselves is striking. The world of two thousand years ago is almost unimaginably different from our own in so many ways. None of the technologies that drive our daily life were in existence. Living standards were immeasurably lower. Lifespans were vastly shorter. Ideas about prosperity, class mobility, security, and life vulnerability in general were inconceivably different then. The people of biblical times did not carry around with them the ideas that we take for granted in our times, such as universal human rights, political equity, or fundamental freedoms. Nor, for that matter, did they have access to people around the globe via a small device in the folds of their tunics.

And yet the examples in the stories retain the ring of authenticity. After all, people still fish, dive for pearls, tend grape vines, sow seed and reap crops, store up harvests, adjudicate inheritances and gifts, build houses with foundations, pay debts (or dont), struggle with income disparity, encounter the poor in their midst, endure inter-family tensions, and experience many of the other variations of life one finds in the parables. The power of the parables endures in part because the examples Jesus chose have proven to be persistent throughout history. They are part of the enduring human condition, while retaining a freshness that prevents them from seeming old fashioned or old tech at all. They appeal to something natural, constant, and ubiquitous in human experience.