The European Qur'an

Edited by

Mercedes Garca-Arenal

Jan Loop

John Tolan

Roberto Tottoli

Volume

ISBN 9783110778595

e-ISBN (PDF) 9783110778847

e-ISBN (EPUB) 9783110779042

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

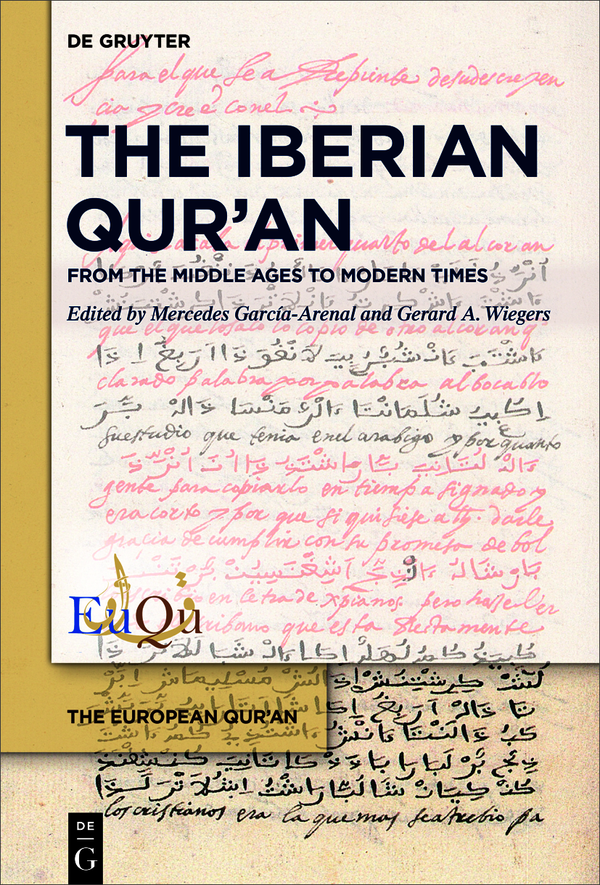

The Iberian Quran and the Quran in Iberia: A Survey

Mercedes Garca-Arenal

Gerard A. Wiegers

Due to the long presence of Muslims in Iberia, both as inhabitants of the Islamic territories (al-Andalus and the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada) and as Muslim minorities in the Christian Kingdoms, the Iberian Peninsula provides fertile soil for the study of the cultural history of the Quran in Europe, the focus precisely of the EuQu project to which this book belongs. This book focuses on Christian Iberia. From the mid-twelfth to at least the end of the seventeenth century, the efforts undertaken by Muslim religious scholars and copyists on the one hand, and Christian scholars and converts to Christianity on the other, to copy, transmit, interpret and translate the Quran are of the utmost importance for understanding the significance of the Quran in Europe. But this book goes beyond the Early Modern period, exploring the significance and knowledge of the Quran in Iberia in Modern times and also in other Hispanic territories, demonstrating the long engagement with the Muslim Holy Scripture well after the times in which Muslim minorities inhabited the Peninsula.

As a result of the long process known as Reconquest, the Northern Spanish kingdoms, slowly expanding their frontiers southwards throughout the Middle Ages, came to contain large minorities of Muslims, the so-called Mudejars (from Arabic mudajjan, i.e., he who has concluded a treaty after the surrender of his village or city), who were allowed, under certain conditions, to preserve and practice their faith. It was the first time in history that significant numbers of Muslims came to live under non-Muslim rule. There were other minorities, the Mozarabs or Arabized Christians, who lived in Muslim lands and remained as a distinct Arabized minority when they emigrated to Christian territory. Muslims (named Mudejars before the orders of conversion) and Moriscos (converted Muslims) interpreted and translated their sacred scripture for their own use as they were becoming increasingly at home in the Romance vernacular and losing the knowledge of Arabic. There were translations from Arabic to vernacular Castilian or Aragonese, written in the Latin alphabet or more frequently in what is called Aljamiado, i.e., Romance vernacular in Arabic script. The first written evidence of such translations appears in Aragon dated in 1415.

A decade after the rendition of the capital city of Granada and conquest of the Nasrid Kingdom, the so-called Catholic Monarchs, Fernando and Isabel, decreed in 1502 the expulsion (to be avoided only by conversion) of the entire Muslim population of the territories belonging to the Crown of Castile. In the Crown of Aragon the Muslim population would be allowed to practice Islam until 1526, when they too were forced to convert to Christianity or face expulsion. The existence of numerous and firmly established Muslim communities in the Crown of Aragon (including Valencia) that were free to practice their faith from the eleventh to the early sixteenth centuries explains the fact that most of the translations and commentaries of the Quran were written and copied in the Aragonese territories, where Christian and Muslim communities had lived side by side for centuries and used a common language to communicate with one another. In Castile, the situation was different. Muslims were a much smaller part of the population, about 3%, against 30% in Aragon and Valencia. Christian Aragonese or Catalan scholars and clerics (from the famous examples of Ramon Mart and Ramon Llull up to Juan Andrs and Joan Mart de Figuerola) had easier access to Arabic or Islamic works than other European scholars interested in studying the Quran, and they had much greater opportunities to engage Muslim or formerly Muslim collaborators to help them study it than they would have had elsewhere in Europe. As far as is known, the earliest Romance Quran translation (now lost) was made from Latin into Catalan in 1382 at the behest of King Pere III el Ceremonis (Peter IV of Aragon, d. 1387).

In Castile the period of collaboration between Christian scholars and Muslims was shorter. But we do have the famous example of the translation of the Quran made by Juan de Segovia in 1456 with the cooperation of the faqih and mufti sa ibn Jbir, a Mudejar, not a convert, who died in Tunis and was buried there. This translation has not been found. The only complete translation of a Morisco Quran that has reached us, known as El Corn de Toledo was copied in 1606; one of its colophons is shown on the cover of this book.

Forced conversion of Muslims to Christianity was completed by the 1520s; those who wanted to remain Muslim had to practice their religion in clandestinity and, from the 1530s onwards, under persecution by the Inquisition. By the end of the sixteenth century, Arabic was still spoken and written in parts of Spain (mainly Granada, Extremadura, Valencia and areas of Aragon) by this population of Islamic origin. Inquisition files contain highly detailed information on the use of Arabic until the expulsion of 1609. And that was so in spite of the fact that Felipe II, by means of a decree in 1567 in the Kingdom of Granada, had forbidden the oral and written use of the Arabic language. This final prohibition of Arabic in 1567 was the main cause of the Morisco revolt of the former Kingdom of Granada known as the War of the Alpujarras, a fierce and devastating two-year war. In effect it required a new Christian conquest of the kingdom, and its aftermath was the expulsion of the Granadan Morisco population to the Northern territories of Castile (157071).

This is the background of a long-term historical situation which makes Iberia a unique case study for the history of the translation of the Quran. On the one hand, no other area of Western Europe knew such an intense and enduring confrontation with Islam; and on the other, no other area had such a close and productive entanglement with Islam and with Muslims, to the point that arguments over Spains Islamic past have been a fundamental element in constructing its national identity.

The religious confrontation produced polemics and disputations, but not only those, as this book will show. Rather, the term polemics covers a complex field of intellectual and religious activity in which the aims of knowing and confuting Islamic doctrine were intertwined and not only directed to Muslims, but also to Christians with the aim of separating clearly what was Christian and what was not. Translation of the Quran for Christians was a tool to convert Muslims; for Muslims it was a protection from being converted, from losing oneself in a Christian majority.

In this book we have intended to consider all facets of the cultural and religious significance of the Quran on Iberian Christian soil: copies of the Quran, translations, dissemination by way of teaching, interpretation and preaching, circulation, collections made by both Christians and Muslims. The contributors to the present volume reflect on a context where Arabic books and Arabic speakers who were familiar with the Quran and its exegesis coexisted with Christian populations, often sharing the same spaces, with Christian scholars and the centres of power and (religious) education. In Christian Iberia, the close proximity of Islamic tradition and sources, and the availability of informants (mostly, but not exclusively, converts), offered Christians interested in the Quran a privileged access to Islam. This is visible in a concept of Islam (even in anti-Islamic texts) that is much closer to the lived experience of Muslims than we find, for example, in early modern Northern European scholarship: a concept of Islam not limited to the Quran, but also more aware of the religious significance of tafsir (exegesis), and hadith (tradition) than in other parts of Europe, where that awareness was almost absent in this period. The collaboration and contacts between the two religions also produced reactions of separation and rejection on both sides; we will see these phenomena when dealing with the action of the Inquisition and the